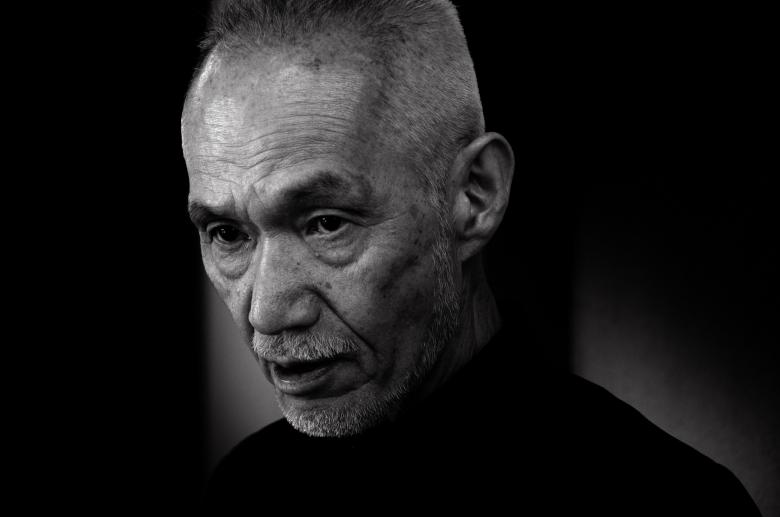

Japanese architect Shin Takamatsu gained fame in and beyond Japan in the 1980s with a “function follows form” approach expressed in stunning graphite drawings and realized in a number of commercial buildings in Kyoto. The architect remains active to this day and has numerous projects on the boards. Vladimir Belogolovky spoke with Shin Takamatsu about his recent work in Vietnam, his design process, who influenced him the most, and why he compares his architecture to making a sword.

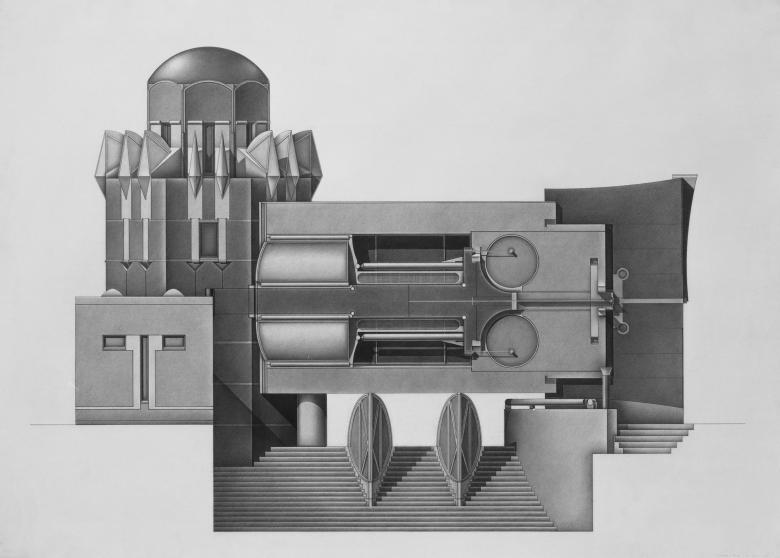

Kyoto architect Shin Takamatsu is known for exuberantly detailed buildings in Japan and throughout East and Southeast Asia, as well as for exquisite, atmospheric drawings, some of which take a whole month to complete. The architect’s creations offer their own unique worlds. As its name suggests, Origin I was his first important built work. It remains unsurpassed as far as achieving, in Takamatsu’s words, “the essence of architecture.” It was designed for a client, the owner of a company that made kimono sashes, who told him, “I want you to make architecture. I’ll worry about the use of it.” Particularly memorable for its abstract facade, the building simultaneously evokes a mask, a gadget, or an alien wrapped in a ceremonial cloth. A keen eye will also spot reinterpreted traces of projects by such Viennese masters as Hans Hollein and Otto Wagner. Symmetrical and introspective, this theatrical architecture flows mysteriously and majestically deep inside the building.

Shin Takamatsu (b. 1948, Nima, Shimane, Japan) came into architecture through drawings and a love of making things. Growing up, he attempted to build a submarine and even a working gun. When he was ten, he felt the incredible power of Izumo Taisha, one of the oldest and most important Shinto shrines in Japan. “Encountering Izumo Taisha as a child,” Takamatsu said in our interview that was interpreted by Thomas Daniell, professor and scholar of Japanese architecture, “I decided that when I grow up, I would make something like that.” His inclinations toward architecture were reconfirmed when he encountered Kenzo Tange’s Yoyogi National Gymnasium, designed and built between 1961 and 1964 for the Tokyo Olympics. For the first time, he learned what architects do. “If I became a person like that,” he thought, “I could build Izumo-taisha.” By then, he was 14, and nothing would deter him from becoming an architect.

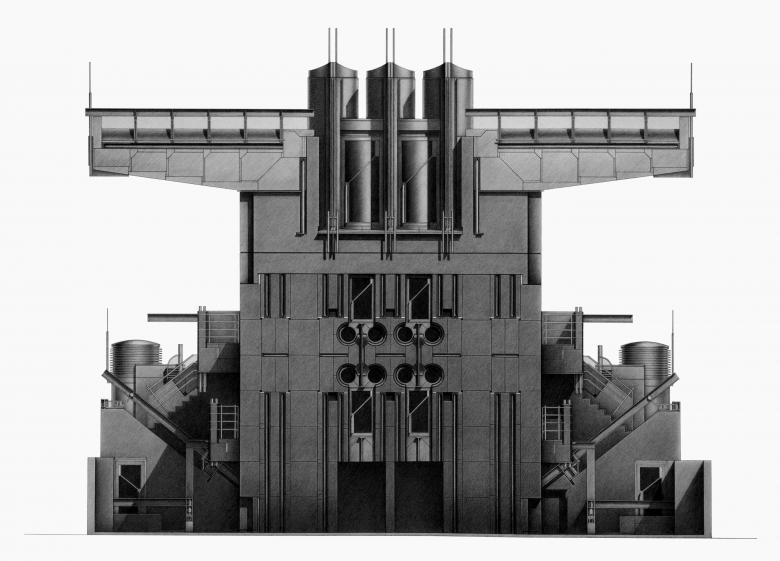

He established Shin Takamatsu Architect & Associates in 1980, following his graduation from Kyoto University, where he earned a bachelors, masters, and PhD degrees in the Department of Architecture and Architectural Engineering. Key early built works include Origin I, II, and III (Kyoto, 1981, 1982, 1986), Ark and Pharaoh dental clinics (Kyoto, 1983, 1984), and Kirin Plaza (Osaka, 1987). Other important buildings are Shoji Ueda Museum of Photography (Tottori, Japan, 1995), Hamada Children's Museum of Art (Shimane, Japan, 1996), Minatosakai Community Center (Tottori, Japan, 1997), Nose Myoken-san Worship Hall (Hyogo, Japan, 1998), National Theatre Okinawa (Okinawa, Japan, 2003), Tianjin Museum (Tianjin, China, 2004), Ba Den Mountain temple (Tai Ninh, Vietnam, 2021), and Sustainable Mobius pavilion at the Osaka-Kansai Expo 2025. Current projects include a temple in Kyoto, a 270-meter-tall hotel and condominium in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, as well as religious, cultural, and commercial buildings in Vietnam and Taiwan.

Takamatsu’s work has been exhibited at the Venice Architecture Biennale (1982, 1985, 1991), the Centre Pompidou in Paris (1988), the Aedes Gallery in Berlin (1991, 1994), and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (1993). His monographs have been published by Mondadori Electa (2012), GA Architect (1990), and Rizzoli (1993). Throughout his career, Takamatsu has taught architecture at his alma mater and the Osaka University of Art.

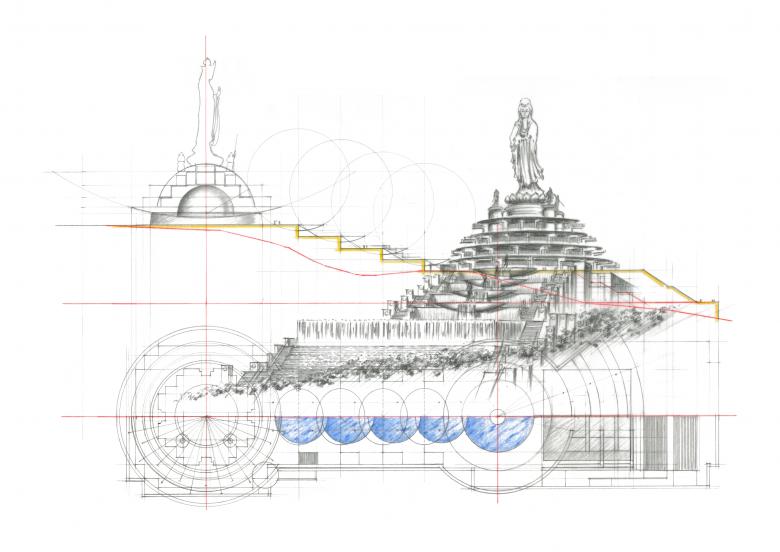

Shin Takamatsu (ST): The project's starting point was to build a place of worship, many of which had been destroyed during the Vietnam War. The client assumed that a Japanese architect with knowledge of Buddhism would do the project. That’s how I received a call. After visiting the site, I realized that it was a 1,000-meter-high mountain that was treated as an object of worship. So, I wanted to symbolically express the sacredness the mountain itself possesses through architecture, without destroying it.

The client’s brief was very abstract: “Create something on this mountain that would be overtly symbolic, something that people could visit at any time and would want to visit.” We were told, “Please send us the first sketches as soon as possible.” I set aside all my other work and just focused on this. When the client saw the sketches and computer animation, I was told, “We want to build it exactly the way you designed it.”

I've always believed that architecture is born in its own unique place, at a unique time, and for a unique client. I think architecture is something that can be born only under such circumstances, which I call a ‘journey.’ Meeting new people, going to new places, experiencing new impressions, while conceiving architecture.

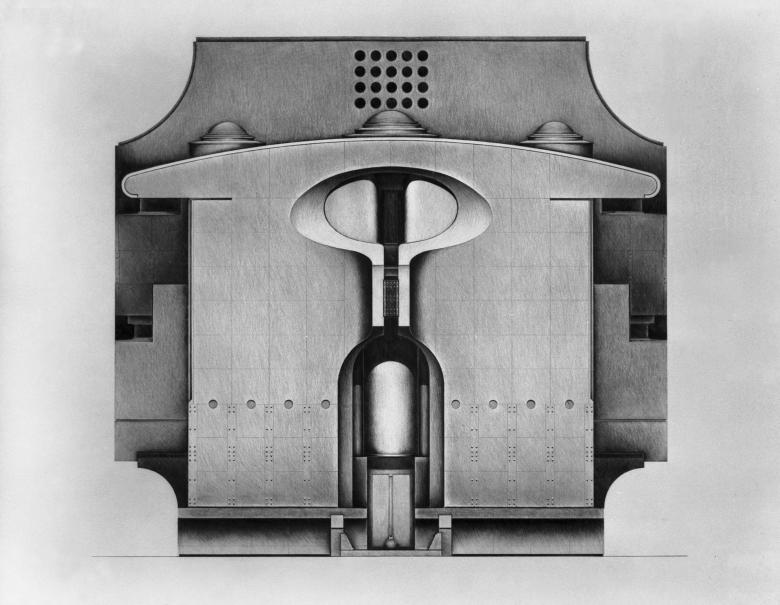

ST: Employing just a pencil, I try to ascertain the power and strength of architecture. I express architecture’s attributes by focusing on its brilliance and the qualities of materials to discover and ascertain its power. I explore architectural ideas through sketches. I think about architecture while sketching and ascertain its various capabilities by thinking with sketches. I repeat this process, intensifying the pressure, until I arrive at the ultimate solution. When I make this discovery, I express the proposed architecture on a single large sheet of paper. Often, it takes hundreds of sketches before such a discovery is possible.

ST: It was my first architectural work. The client said, “I have nothing to tell you. Just build me architecture. Whatever architecture you build, I’ll use it.” So, for my very first work I was asked to think about architecture. Well, I agonized over the origins of architecture and how to express that. I met the client at a wedding. He saw me signing my name in calligraphy and asked, “What do you do for a living?” I replied, “I’m an architect. I design buildings.” He asked me, “What have you built?” I replied, “Nothing at all.” He said, “Well, would you please build me my company’s headquarters?” That's how it all began.

After visiting the company’s existing building, I understood that no conventional design would be satisfactory. When I asked, “What should I design?” he said, “I want you to make architecture. I’ll worry about the use of it.” I was given only two weeks. So, I sketched almost without sleep, but I couldn’t come up with any ideas. At the very end, as I kept sketching, my hands started moving on their own. I still remember feeling that my hands had discovered the final design. When I brought that sketch to the client, he said, “Okay, let's build this.”

I think the fact that my hands finally “discovered” something was probably due to the sheer number of sketches I’d made up until that point. My hands had memorized them. The final sketch was born from the memory of my hands. What I showed the client was a sketch of the facade, and there were absolutely no changes. He asked me to build it exactly like that.

ST: Well, my first encounter with architecture was Izumo Taisha Shrine. It appealed to me. I felt it constituted the essence of architecture. I try to discover that essence through architecture that is only possible at a given time, under particular circumstances, on a specific site, and with a unique client.

ST: First, I would name Hans Hollein. He said, “Everything is architecture.” I find these words very vivid and powerful. To me, this means that something that is “not architecture” can be found within the very existence of architecture. His Retti Candle Shop really amazed me. I saw a tiny photo of it in the newspaper, just the facade. That little candle shop looked like a gigantic religious building. When I actually went to Vienna and saw how small it was, I couldn’t even recognize it as “small.” I still thought of it as architecture on an enormous scale. Talking about Vienna, I was also deeply shocked and influenced by Otto Wagner’s architecture. This goes without saying, but I am referring to the Austrian Postal Savings Bank.

Among other architects, I would name two other Austrians: Walter Pichler and Raimund Abraham. Another influence comes from Piranesi's drawings. And from Japanese architects, I should mention Sei’ichi Shirai, whose most impressive project is the Temple of Atomic Catastrophes. It was never built, but I see it as the culmination of his search for the simplest, most powerful architecture. It is a very straightforward, essentially a cube pierced by a cylinder, yet explosive composition, something I try to achieve in my own work.

ST: Through architecture, I want to create, how should I put it … architecture outside of architecture as we know it. That's why it sometimes seems excessive and attracts all kinds of critiques. Do you know Nageire-dō? It is also a religious building, but very small. I saw it as a child, and it had a tremendous impact on me. People who visit Nageire-dō will write their name and a wish on a talisman and throw it from its balcony. This kind of architecture has nothing to do with theories and deconstructivism. In my own work, I don’t want to be fixed on any particular idea either. I want my architecture to be different every time.

ST: I might think for a long time without even picking up a pencil. Then I’ll start drawing while I’m drinking. But my usual way is to draw a lot of sketches. Sometimes, an idea may come from the first sketch. Origin III was like that. I drew some sketches on a single piece of paper. One of them became the basis for the project.

ST: I’ve actually designed a sword, which is sitting here in my room. I called it Killing Moon. When I said a ‘sword,’ I wasn’t thinking of a typical, classic Japanese sword. Rather, I was thinking about the kind of sword I would make if I were to create one, and so I created architecture that I call a sword. What I mean is that making a sword and making architecture are similar. I created the entire sword by assembling polished parts. I use exactly the same method when I create architecture.

I see my buildings as an extension of my body. I think with my hands. I create architecture while sketching. In a sense, I create architecture while thinking with my hands. That's the kind of architect I am. When I create architecture, my body flows directly into it.

ST: All I can do is share my own experience—think about architecture with your hands.

相关文章

-

-

Isabel Zumtobel: 'We Believe in the Power of Design to Change the Future for the Better'

World-Architects Editors | 18.11.2025