The Thermal Baths in Sidi Harazem, Morocco

A Brutalist Complex in Need of Attention

On a recent trip to Morocco, Eduard Kögel visited the Sidi Harazem Thermal Bath Complex, a masterpiece of brutalist architecture that was designed by Jean-Francois Zevaco in the 1960s but is now in need of repairs. Read about the project, its current conditions, and the plans for its future.

When large concrete buildings show signs of serious aging, more than strategic measures are required to breathe new life into them. Additionally, the focus cannot be solely on architectural preservation. Above all else, the focus must be placed on involving the local population to achieve the greatest possible benefit for them. With financial support from the Getty Foundation’s Keeping It Modern program, the Fez-based architectural office Aziza Chaouni Projects has been working on plans for the thermal baths in Sidi Harazem since 2017. With their proposal, the architects want to bring contemporary life back into the 1960s complex designed by Jean-François Zevaco. But so far, it remains in a deep slumber.

The French architect Jean-François Zevaco (1916–2003), who was born in Morocco, was undoubtedly one of the most important figures in the country in the second half of the twentieth century. His multifaceted complex for the thermal baths in Sidi Harazem, in the countryside close to Fez, was built from 1958 onwards. It is an icon of the brutalism that nevertheless subtly incorporates regional design features. In these details, many of which have been preserved to this day, Zevaco’s architecture is reminiscent of Frank Lloyd Wright’s and Carlo Scarpa’s sensitively designed concrete buildings. Unfortunately, the complex is not in a good state of repair, and many areas have either been altered by informal constructions or are long closed for use due to significant structural problems.

For the renovation, Aziza Chaouni Project partnered with the Moroccan State Pension Fund (Foundation CDG)—the owner of the complex—and its subsidiary Hotels and Resorts Morocco (HRM, a branch of the CDG). A conservation management plan was prepared with funding from the Keeping it Modern grant from the Getty Foundation in Los Angeles. The non-profit CDG Foundation supports the project as part of its social responsibility program, and HRM manages most of the facilities. Although launched in 2017, the renovation project was significantly delayed by the pandemic and is still awaiting commencement.

As the entrance feature to the complex, Zevaco designed a slender concrete tower from which a path leads to the hotel located to one side, and several successive staircases and platforms lead to the iconic circular pool of the thermal baths on the other side. The tower is a collage of differently designed, overhanging concrete blocks reminiscent of constructivist models. The plant boxes integrated into the structure have not been maintained, and the nighttime lighting has long since failed.

A “great canopy” covers the main public square, which is accessed via a staircase and serves as a distribution point. From there visitors could originally access the palm grove and swimming pool, the hotel, and a market. The public square covers 3,000 square meters and is spanned by a series of Vierendeel trusses. Beneath it are planters, seating areas, water basins, and a fountain, which drew people from far and wide to take water home with them. Today, the water basins next to the fountain are dry and an informal market has established itself under the great canopy, obscuring the sequence of spaces.

At the end of the platform overlooking the landscape, a large staircase, originally partially covered by a pergola made of wooden logs, leads down a steep slope. At the bottom, the path splits, with one side leading to the swimming pool and the other to the hotel’s 71 bungalows, which are currently in a state of disrepair. The staircase lost all its poetic power with the disappearance of the wooden trellis that provided shade. The water basins next to the staircase, as well as the entire water circulation system, are out of order and in a state of disrepair.

The centerpiece of the complex has always been the swimming pool, which consisted of a small circular pool for women and a separate large pool for men. Both pools were partially covered by a circular mushroom-shaped roof. The pool area has been significantly altered in recent years by informal extensions to the peripheral areas and inappropriate “renovations.” These have broken the connection of the pool area to the surroundings. Dismantling these additions would be of considerable benefit to the integration of architecture and landscape.

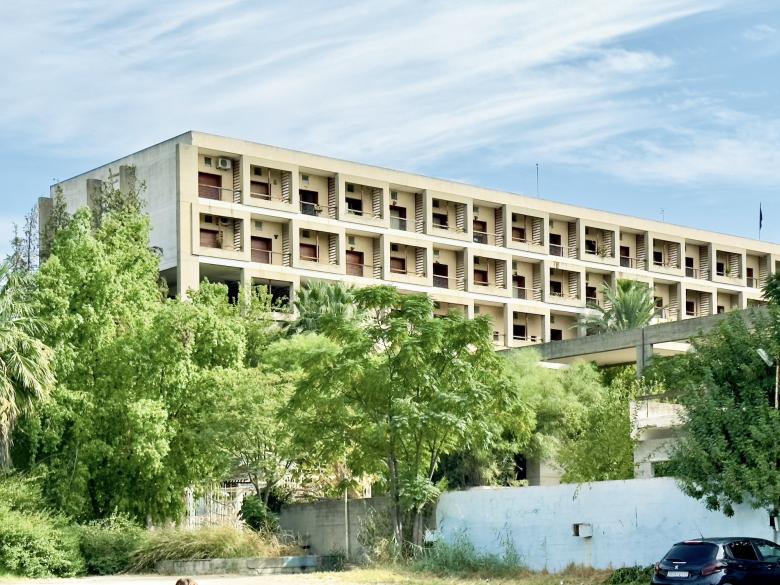

The hotel is located next to the entrance monument and is accessible on the ground-floor level from the street. The reception area, a lounge, a bar, and a dining room, as well as a kitchen and administration offices, are all located on the ground floor of the three-story hotel building, which hovers above the adjoining sculpturally designed garden landscape, providing visitors a view of the entire oasis. The two upper floors house a total of 64 hotel rooms. The original furniture and furnishings, some of which are still preserved, are made of wood. Zevaco also used copper, burlap, and small tiles for the surfaces and designed passive cooling circulation systems to avoid the use of electric air conditioning.

Although the hotel is still in operation today, the gardens and grounds are closed to visitors. The building stands on eight V-shaped supports that span an undercroft space with sculptural fountains. Over the years, the entire exterior of the hotel has been “beautified” through several inappropriate renovations. The original architectural references to materials, passive air conditioning, and abstract forms of traditional architecture have been obscured under a layer of decoration in an effort to adapt the complex to rather banal, popular taste.

Beneath the floating volume of the hotel lies the now enclosed courtyard garden with its sculptural concrete surface of water basins, plant boxes, and watercourses framed by pergolas. Over the years, many parts have been covered with small colorful tiles that clash with the original architecture. The water systems have long been out of service and need to be cleaned and cleared of wild vegetation.

On the western side of the complex, Zevaco built 71 courtyard bungalows of one, two, and three rooms, each with a terrace, which were intended for families. Between the units, wooden pergolas covered with bougainvillea created shaded paths leading to small squares. This complex has been closed since 2003 and is now in poor condition. Vegetation has overgrown the paths and courtyards, and the water channels and pumping system here are also broken.

At the lower end of the courtyard garden is the market square, which is covered by 25 pyramid-shaped pointed roof elements, each standing on a supporting pillar. Thirty stalls were once arranged underneath, with a café, bar, and restrooms in the middle. This is the architectural endpoint of the courtyard garden, which begins at the entrance platform and leads under the hotel via several terraces to this expressive covered roofscape. The café and market have long since closed, plants are growing out of the joints of the sculptural concrete landscape, and the water has long since dried up.

The new master plan by Aziza Chaouni Projects envisages various measures that were developed in several workshops with residents, ranging from the demolition of buildings to reveal the original design, to the addition of buildings for new functions, including a spa, medical center, exhibition hall, and library. The hotel, the courtyard houses, and swimming pool are to be renovated, the courtyard garden is to be transformed into a botanical garden, and a gastronomic center is to be created under the expressive roofscape.

The catalog of proposed measures is convincing but its realization will require huge investment. So far, not many concrete renovation steps have been taken in this regard, and the few visitors that come are being put off with promises of a better future. The architects remained silent when asked via email about the start of the renovation work and the hotel management stated that work would begin “shortly.” A renewal of the complex would be more than desirable, as it is an outstanding example of brutalist architecture in Morocco and reflects the optimism that prevailed after the country’s independence.