Robert A.M. Stern, 1939–2025

Remembering 'The King of Central Park West'

Robert A.M. Stern, the famed neotraditional architect, longtime dean of the Yale School of Architecture, and author of a series of definitive books on New York City architecture, died on November 27 at the age of 86.

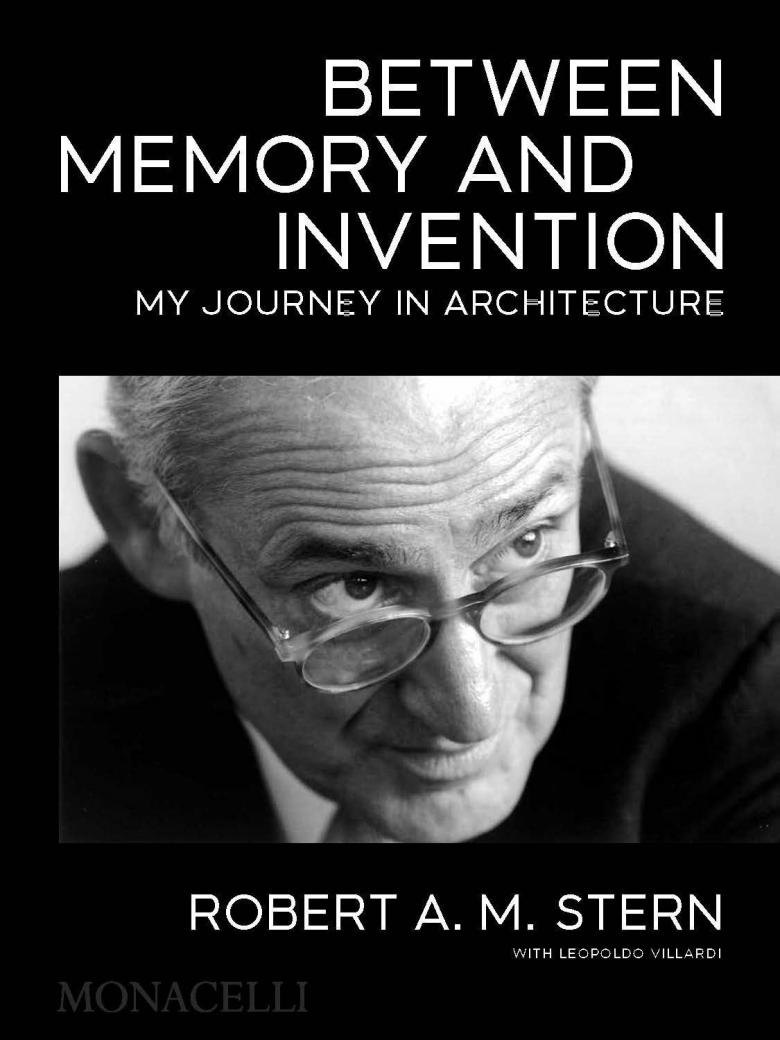

Born in Brooklyn on May 23, 1939, Robert Arthur Morton Stern wrote in his autobiography, Between Memory and Invention: My Journey in Architecture (2022, with Leopoldo Villardi), that he wanted to be an architect “from adolescence,” he wanted “to design buildings like those I saw on the Manhattan skyline.” That desire was fostered by early experiences like a visit to Marcel Breuer's House in the Museum Garden at MoMA in 1949 and in Stern's own Breuer-like design of a house that earned him third place in Pratt Institute's architecture competition for high school students in 1954. Instead of attending Pratt in Brooklyn the following year, as might be expected for an aspiring architect raised there, Stern headed uptown to Columbia University, earning a bachelor's degree in history in 1960. Although Stern knew he did not want to attend Columbia for graduate architecture school, he recalled in his autobiography that his experiences in Avery Library were foundational in the series of New York books he would eventually write between 1983 and 2025.

Stern enrolled in Yale University in the fall of 1960, fortuitously when Paul Rudolph was chair of the Department of Architecture. Halfway through Stern's five years at Yale, the architecture school moved into the Art & Architecture Building, the Brutalist masterpiece designed by Rudolph that would be expanded and renamed (to Rudolph Hall) under Stern's deanship a half-century later. Stern described his time at Yale as a “struggle to break with orthodox modernism,” and an expression of that struggle can be seen in the double issue of Perspecta, the architecture school's annual student-run journal, that he edited in 1965, his last year at Yale. Perspecta 9/10 has projects and remarks by Alvar Aalto, Louis I. Kahn, and Paul Rudolph, but it is best known for including excerpts from Robert Venturi's then-forthcoming Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture and Charles W. Moore's essay “You Have to Pay for the Public Life.” Both contributions signaled the postmodern shift overtaking the architectural profession at the time.

After Yale, Stern moved back to New York City, earning a fellowship at the Architectural League of New York; it culminated with his curation of 40 Under 40: An Exhibition of Young Talent in Architecture in April 1966. Then 26 and with just one house under construction, Stern nevertheless included himself on the list. Before launching a practice in 1969 (as Stern & Hagmann, with Yale classmate John Hagmann), Stern worked for two years in New York City's Housing and Development Administration, an experience he admitted he “did not love.” Although Stern and Hagmann were busy designing and building houses in the Hamptons in the first half of the 1970s, Stern remained active with architectural discourse in print. The most attention-getting piece at the time was “Stompin' at the Savoye,” which Stern wrote for the May 1973 Architectural Forum as a reaction to the 1972 book Five Architects, which presented projects by Peter Eisenman, Michael Graves, Charles Gwathmey, John Hejduk, and Richard Meier. Stern's piece fed a “Whites” versus “Grays” debate that broadly pitted modernism against postmodernism. Curiously, Stern designed a facade for the townhouse at 870 Park Avenue in 1975 that seemed to balance both poles, with its classical symmetry offset by stark surfaces and abundant glass; it was a signal his struggle with orthodox modernism continued.

Stern and Hagmann were together for seven years, so in 1977 the firm was renamed Robert A.M. Stern Architects. Now known as RAMSA, the New York City practice numbers 300, designing primarily houses and apartment buildings, libraries and university buildings. Stern's own postmodern tendencies, evident in such projects as the Best Products showroom from 1979 and his late entry for the Chicago Tribune tower competition a year later, were tempered over the course of the 1980s, such that in the 1990s and later, the buildings he designed were unabashedly traditional. Some were neoclassical, like the Darden School of Business (1996) or neo-Gothic, like the Yale Residential Colleges (2017), though ultimately Stern's buildings embraced various traditional and vernacular styles. The remembrance of Stern at RAMSA phrases his approach like this: “Bob Stern believed that design is an ongoing dialogue between memory and invention—a bridge between what has been and what could be. He defied passing trends, remaining steadfast in a timeless and contextual approach that he believed was an architect’s responsibility to society. He understood that every place has a unique history and character that cannot be expressed with a singular style.”

Stern's move toward what he called “modern traditionalism” made him something of a controversial choice as the sixth dean of Yale School of Architecture, a post he took up in September 1998. Fears of the curriculum shifting toward a preference for historical styles in the studio were quickly assuaged, as Stern used his “expansive Rolodex” to bring in big-name and up-and-coming architects from around the world as visiting professors. So, alongside Peter Eisenman, Philip Johnson, Cesar Pelli, Frank Gehry, and Glenn Murcutt were Brigitte Shim, Tod Williams and Billie Tsien, Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara, and the architects from FAT and Muf in the UK, among many others. “As I saw it,” he wrote in his autobiography, “students should become familiar with the grand tradition of classicism with all its myriad permutations as well as the anticlassicism of modernism.”

Stern was dean at Yale until 2016, maintaining his commute between New Haven and New York City over those nearly two decades. His firm continued to grow, busy with residential and institutional projects, none more famous than 15 Central Park West, a luxury apartment building for Arthur and William Zeckendorf on a full-block site near the southwest corner of Central Park. RAMSA responded to the complicated zoning rules by breaking the project into two buildings: "the tower" on the west, along Broadway, and “the house” on Central Park West, directly across the street from the park, both linked by a low lobby with amenities; consistent across both are large windows set into stone facades and setbacks at the upper floors. When it was completed in 2008, the sale prices of the units were the highest ever in New York City, with an average per-square-foot price of $3,300, leading Paul Goldberger to dub him “The King of Central Park West” in Vanity Fair. Not surprisingly, the success of 15 CPW led to a spate of limestone- and brick-clad apartment buildings designed by RAMSA since, most known simply by their addresses: 30 Park Place (2016), 220 Central Park South (2019), 520 Park Avenue (2019), 200 East 83rd Street (2023), and 255 East 77th Street (under construction), among others.

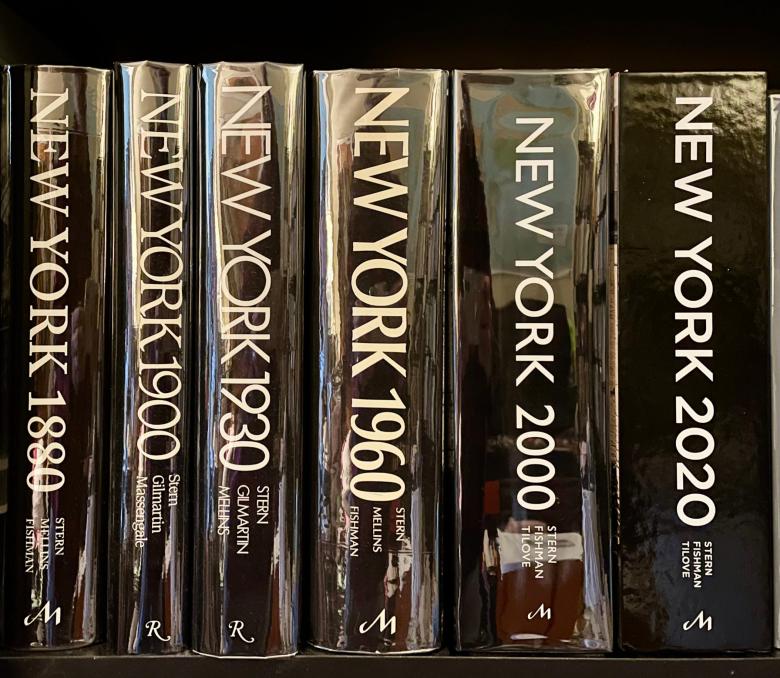

Clicking on the links for the handful of apartment buildings listed above reveals how most of recent projects in the office have been designed by other partners at RAMSA, a product of Stern, in his words, “passing the baton” to his successors. One of the last works Stern completed before his death was the publication last month of New York 2020: Architecture and Urbanism at the Beginning of a New Century, a 1,500-page tome written by Stern with David Fishman and Jacob Tilove: the sixth and final installment in an encyclopedic series of books covering 150 years of New York City architecture. Stern began the series in the early 1980s and added to them fairly regularly over the ensuing decades, with each book covering a roughly 30-year period. The breadth and scholarship (not to mention the heft) of the books are extraordinary, making them indispensable for anyone interested in New York City architecture. For an architect who was born in New York and as a child glanced at its skyline, knowing he wanted to be an architect, the books are a symbol of Stern's lifelong passion for the city and its architecture. But they are also expressions of the life he lived, particularly for the way he managed to take on many different roles and produce many different things—all at an equally high level of quality and intensity.