What Are You Afraid Of? On Hope over Fear in a Globalized World

Madeline Carey reviews Building for Hope: Towards an Architecture of Belonging, the new book by Marwa al-Sabouni, a follow-up to The Battle for Home, the memoir that brought the Syrian architect international acclaim five years ago.

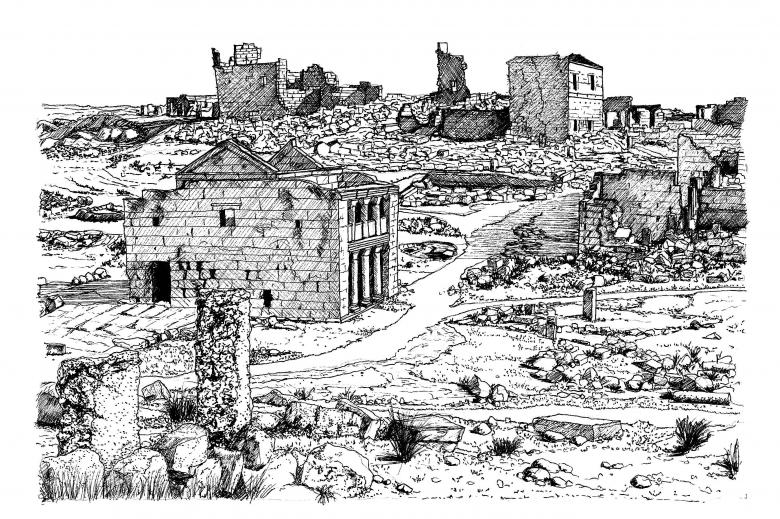

Marwa al-Sabouni is a Syrian architect. In 2016 she published The Battle for Home: The Vision of a Young Architect in Syria, an elegy to her hometown, Homs, and a grueling personal account of war and survival through the eyes of an architect. That first book makes the bold argument that the built environment and public planning, or lack thereof, have a direct effect on armed conflict and the possibility, or impossibility, for collective renewal and peaceful coexistence. The Battle for Home was widely read and very much celebrated, launching an international career for an architect who was practically unknown outside of her native Syria before then. Al-Sabouni became a well-known, much sought-after, public speaker and was reportedly considered a contender for the Pritzker Prize in 2018.

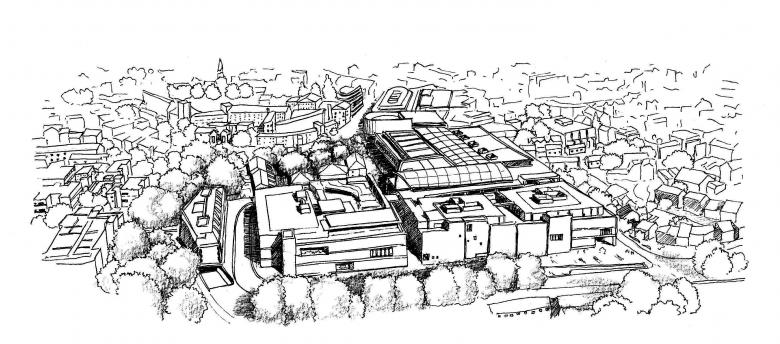

Her new book, Building for Hope: Towards an Architecture of Belonging, is an ambitious treatise that combines stories from daily life in Syria with observations of cities such as Detroit, Helsinki, Bristol, Beirut, Dubai, and Amsterdam. Al-Sabouni’s husband and daughter appear alongside ancient philosophers. Their life stories — their travels, migrations, hopes and dreams — are just as important as those of more famous thinkers.

Building for Hope is expansive, abstract, and at times extraordinarily idealistic in a way that reminded me of another book born out of the ashes of war, Muriel Rukeyser’s 1949 classic The Life of Poetry. Both books explore and reinterpret ideas from a wide range of thinkers — philosophers, scientists, urban planners, musicians, poets — and traditions. Both al-Sabouni and Rukeyser ask huge, fundamental questions: what does it mean to belong? How do we rebuild after conflict? Does beauty matter in the aftermath?

In the years just after the Second World War, Rukeyser wrote her sprawling book of essays with a rather simple, yet audacious, thesis: poetry can be an essential agent of change. Rukeyser’s now famous opening chapter is called “The Fear of Poetry.” Al-Sabouni, some seventy years later, argues that architecture is a necessary agent for any kind of peace, any possibility of belonging in our modern, extremely polarized world. Building for Hope is structured in five parts, around five kinds of fear: “The Fear of Death,” “The Fear of Need,” “The Fear of Treachery,” “The Fear of Loneliness,” and “The Fear of Boredom.” This structure alone was enough to pique my interest; few books about architecture tackle such philosophical questions.

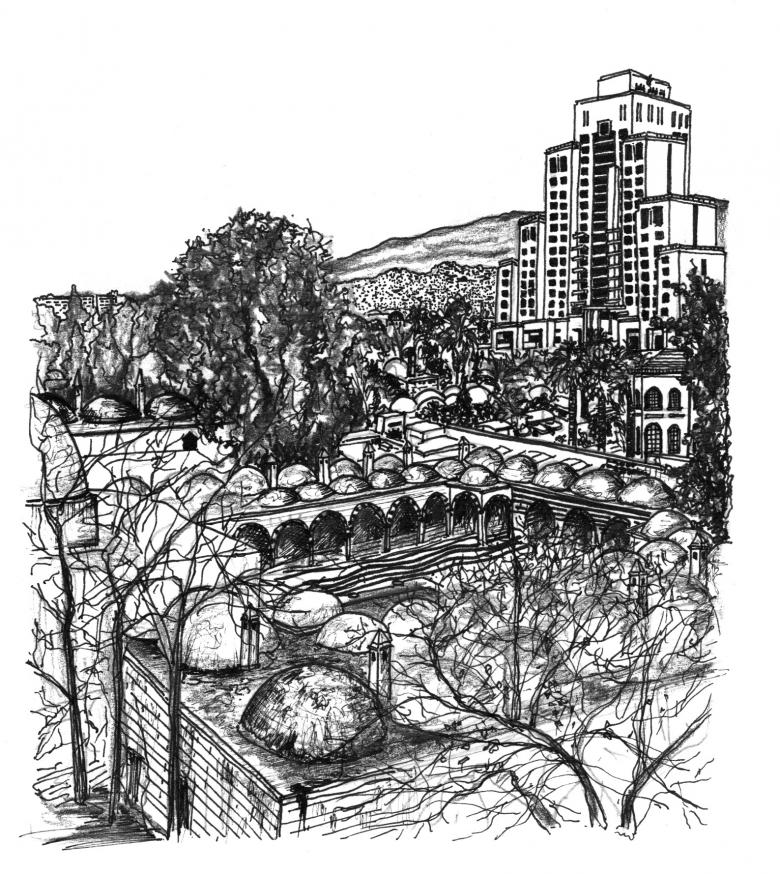

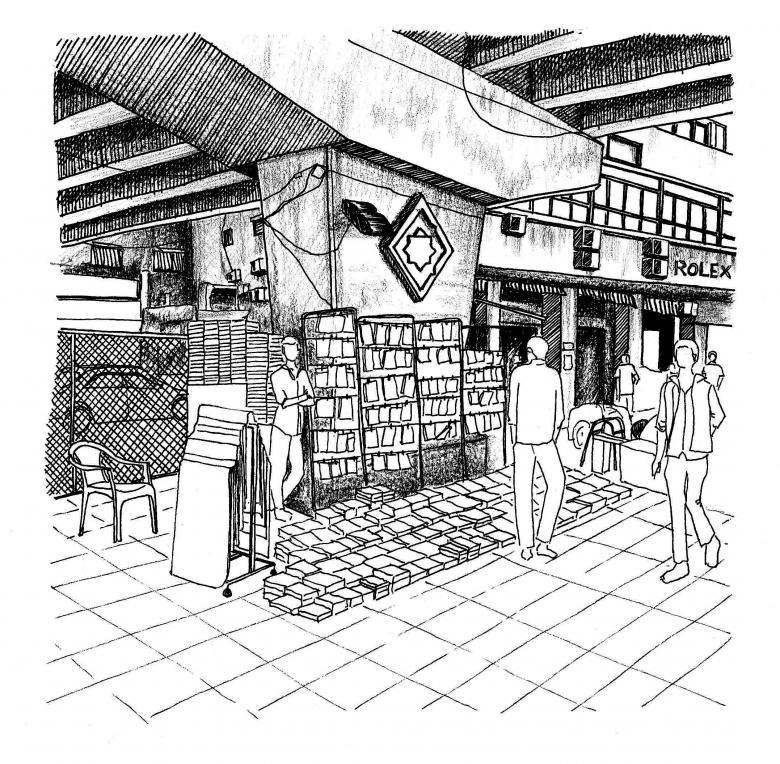

Each chapter interweaves ideas from philosophers, urban planners and poets with concrete examples of failing, flailing cities — from Detroit, the “Factory City” par excellence, to Dubai, a modern, shiny, soulless shell. Al-Sabouni reaches far back to give us a thorough explanation of settlement, building and urban planning in the Levant and the ways in which capitalism, colonialism, and corruption have fueled ethnic conflict and urban decay. But she constantly weaves a many-layered narrative, giving glimpses of modernity in her part of the world as well as in the West. It’s especially enlightening to read about Western cities through the lens of an architect specialized in Islamic traditions.

Throughout the book, al-Sabouni provides the Arabic words for concepts that a native English speaker can grasp but perhaps not fully comprehend. This reader took copious notes and made a long list of concepts to explore and investigate; of authors to read and reread, from Arthur Schopenhauer to Jane Jacobs to Ibn Khaldoun.

The third chapter, “The Fear of Treachery,” provides a thorough background to help readers better understand the conflict so often referred to in the West as Syria’s “civil war.” Al-Sabouni highlights the myriad of ways in which French planning led to the destruction of a cohesive, tolerant, multi-ethnic society. She excavates how France’s penchant for “the modern” or for “improvements” led to a colossal unraveling of centuries of cohesion.

The next chapter, “The Fear of Loneliness,” explores the Garden City movement and provides beautiful, richly observed descriptions of the author’s experience in the cities and monuments of her own country:

The book could benefit from the author inserting herself into history — into the buildings, the structures, the cities — a bit more frequently. At times, when al-Sabouni departs from the specific, she veers dangerously close to being overly simplistic, to stating the obvious. There is a certain naivety and reliance on platitudes that could provoke readers to wander, to stop trusting the writer as an expert, erudite guide. “Syria,” the author tells us, “like much of the world today, has become a Monopoly board for property investment rather than a home for anyone.”

“One thing is certain,” she continues, “agriculture and trade, the two crucial elements of the ancient world are now being used to turn the whole of our modern world into a mass-production system of Factory Cities and Factory Villages. And this, as history tells us, leads to famine and war.” Such passages are the weak spots in the book, the hollow sections in which the prose isn’t nearly as smart as the author. These overly broad brushstrokes made me think this could have been a shorter, stranger, better book if al-Sabouni had stuck to more specific examples and trusted in her remarkable ability to compare and contrast ways of living — and ways of belonging — in different cities around the globe.

The most insightful and engaging sections of the book delve into the nitty-gritty of the local. In the final section, “The Fear of Boredom,” we get a thorough and thought-provoking explanation of the miri lands, informal settlements in Syria. It would be extraordinary to read a comparative study of such illegal or quasi-legal land ownership schemes throughout what was once part of the Ottoman Empire as well as throughout today’s Mediterranean. Al-Sabouni would certainly be the person to lead such a project; the implications of such practices on displacement and inflated real estate pricing are key to the most pressing policy debates in cities all over the world. What’s for certain is that we need more people — more architects, more writers — like Marwa al-Sabouni: global citizens with a sharp eye for detail and an unwavering, deeply ethical commitment to the places they call home.

Building for Hope is dense and daring. Readers will finish with a list of people and places to investigate, as well as with a firm belief that a better future lies in valuing community over ostentation, coherence and decency over luxury, truly livable cities over places designed purely for profit. Exactly how to build such hopeful spaces remains to be thoroughly explored and explained, but a woman from Homs is sure to be part of the global conversation about possible paths forward.

Building for Hope: Towards an Architecture of Belonging

Marwa al-Sabouni

23.4 x 15.3 cm

224 Pagina's

24 Illustrations

Hardcover

ISBN 9780500343722

Thames & Hudson

Purchase this book