Architecture Born from the Spirit of Drama

Holger Kleine’s book The Drama of Space aims to help a general audience, not just architects, understand the effects that spaces have on people. By analyzing buildings through drama, the book is also, so argues Georg Windeck, a discourse on architecture's receptiveness to other disciplines.

An architectural experience unfolds when a building is explored room by room. The appearance of a space is established not only by its own features, but also by the other parts of the building that we have to pass through to get there. Their colors, proportions, illumination may have been in stark contrast or complete agreement with our current visualization, hence emphasizing or suppressing particular aspects of its design. In the same terms, a room will continue to inform our senses as we move on to other places. This “succession of events that constitute dramatic experience” associates architecture with the artistic disciplines of music, theater, dance, and film. They all create a dialogue of meanings and tell a story along an aesthetically controlled timeline: drama in its broadest sense.

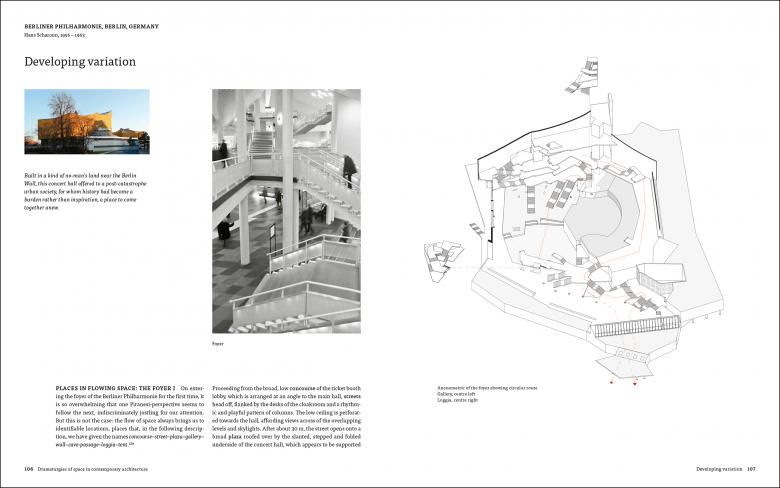

In The Drama of Space architect and musician Holger Kleine sets out to establish a comprehensive theory of dramatics for architectural design. Using photos, plans, and diagrams, he explores the means and methods with which builders can work as dramaturgists. The book is divided into four parts. In the first, Kleine introduces basic principles of spatial dramaturgy, using the Venetian Scuole Grandi as examples. The second part of the book analyzes dramaturgical models of the performing arts. Here he establishes a vocabulary, which he then uses in the discussion of contemporary “dramatic” architecture in the third part. In the fourth, Kleine concludes with typological design guidelines for creating a building as a compelling spatial drama.

The book is a discourse on how architecture has the capacity to be understood and redefined through the knowledge of other disciplines. According to the author, the work of an architect has similarities with that of a script writer, composer, movie director, or choreographer. Theatrical plays can for instance be understood as spatial geometries: Becket’s Waiting for Godot is a “construction of points” that simultaneously opposes and connects two figures in a confined space. Aeschylus’ Agamemnon is on the other hand a “shaft,” whose depth gradually reveals the scandalous dimension of a past event. In similar terms, Kleine materializes musical genres as tangible forms: a Renaissance canon is a “cyclical arrangement of musical cells, diagonally interwoven” and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Fantasia in D-Minor is a “structure built from uneven fragments.”

Just as Kleine architecturalizes the performing arts, his descriptions of actual buildings become melodic, cinematographic, and tragic: the Glasgow School of Art by Stephen Holl is a “brutalist symphony” in which the “remembered sound of construction” is tangible by sight and touch. In its abrupt “slicing together” of spatial bodies, the “obstinate noise” of its concrete stairs and landings is “muffled” by the pristine whiteness of its sleek wall finishes. The Lincoln Road Car Park in Miami by Herzog and de Meuron is a “ballet of pirouetting pillars.” They perform a pas de quatre in different acts of the performance, that is, on different decks of the garage. City and sky are the backdrop for a dynamic choreography of building structure and circulation. The Louvre Lens by SANAA is a motion picture, in which the cuts between scenes, that is, rooms, are blurred with glass and metal filters of varying transparencies and curvatures. The room-high glazing of the entry hall makes the surrounding landscape appear as a full-wall screening, and the absence of any sound intensifies the visual experience of the environs, “making the outdoor present in the indoors as a silent film.”

In his promenade dramaturgicale, Kleine does not categorize artistic references by the time of their creation. This makes us understand that the despair of an ancient tragedy can today be as disturbing as the anxiety of a contemporary Dogme 95 movie. And the melody of a medieval cantata can be as calming as the meditative sound of an electronic twelve-tone piece. The reader learns from this discussion that dramatic effects of architectural space are powerful beyond history and style. They emerge from a strong conceptual idea that “reveals itself gradually through senses and reflection.”

Using Kleine’s own terminology, we can think of his book as a fantasia, a beautiful arrangement of uneven fragments including captivating photos, diagrams and text, that does not follow a strict form. His discussion of the performing arts is inspiring in a visual way that lets us see architectures emerge from sound and play, and the discussion of built works makes us feel suspense and melodic delight. In this dramatic composition of ideas, joyful and dark experiences are equally important and complement each other. Comical buildings are as meaningful as serious ones, like in the ancient Greek drama tragedies were always accompanied by satyr plays. This speaks to Kleine’s dramaturgical understanding of architecture. The essential importance is that they have a transformative effect on their visitor. A walk through a building can change us like the sound of an orchestra or the movement of a dancer.

The Drama of Space: Spatial Sequences and Compositions in Architecture

Holger Kleine

30 x 24 cm

296 Pages

350 Illustrations

Hardcover

ISBN 9783035604313

Birkhäuser

Purchase this book