A New Bilbao Effect

A remarkable exhibition at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark – the latest in its “The Architect’s Studio” series – portrays the aspiring architect Tatiana Bilbao: the only woman in the mega-city of Mexico City running her own architectural practice.

Latin America is currently experiencing a wave of civil unrest. From Venezuela to Colombia, from Brazil to Chile and Argentina, the painful division of societies into the poor and the super-rich has pushed many people to take to the streets. Local architects, too, seem torn between designing millionaire’s villas and new concepts for social housing. Nowhere is this balancing act more evident than in the buildings of the young Mexican architect Tatiana Bilbao, who is regarded as a prodigy of Latin American contemporary architecture. Her country’s historical and cultural roots intertwine with the theme of urban and rural landscapes to become the main threads of this large and elaborate exhibition now on display.

In recent years the Louisiana Museum has extended the excellent reputation it enjoys in the world of fine arts to architecture. Exhibiting architecture is difficult, yet thanks to curator Kjeld Kjeldsen and his team its architecture exhibitions are successful. Unfortunately, they miss the most important qualities of the museum’s galleries: the relation to natural light, nature and the nearby sea. As the latest in the "The Architect's Studio" series, The Architect's Studio - Tatiana Bilbao Estudio focuses on Tatiana Bilbao’s methodology and approach, not the built work. Architecture should have an immediate effect on people, says Bilbao – a new "Bilbao effect."

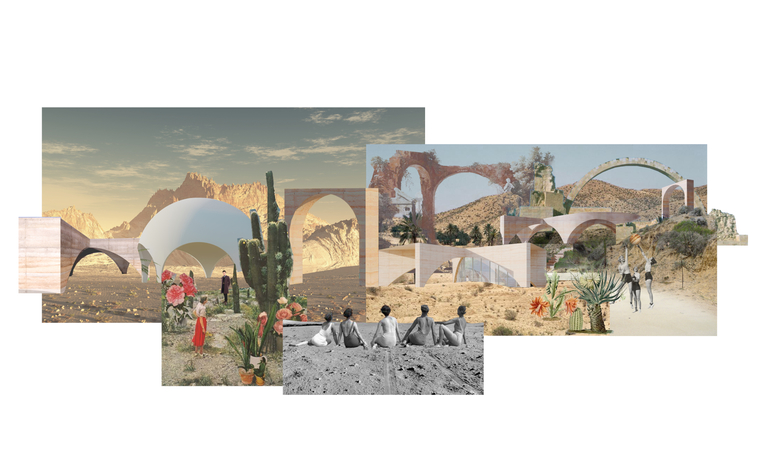

The show leads visitors from sketches and collages to magnificent models and to buildings. A giant in-situ sketch stretches from the floor to the walls. Bilbao has borrowed works of art from the Museo Nacional de Arte and assembled them into interesting collages. In a cabinet, 18 of her studio’s buildings want to be discovered as models and material samples.

While there are lots of people in Mexico who are not literate, many educated people cannot read a floor plan. That's why Bilbao uses collages, assemblages and hand drawings to communicate her design ideas. “The collages bring together utopia and reality” she says. Bilbao insists on the analog – the physical – and distances herself from branded architecture and 3D rendering. She only uses CAD for engineers and craftspeople. Thus, the exhibition focuses on process: from concept to construction.

Bilbao first demonstrated her design skills with a pavilion at Jinhua Architecture Park in China, for which artist Ai Weiwei and Swiss architects Herzog & de Meuron invited 17 architects to design some follies. Only with her villas did Bilbao find the way to inhabited architecture. Casa Observatorio hides in the steep rocks on a stretch of coast in Puerto Escondido, Oaxaca, a round, shallow pool at its center. The remote retreat had to be built by local workers using local materials. Bilbao therefore used the simplest construction methods. "Many workers are poorly educated, but complex architecture can also be made with simple shapes and technologies," she says. "We work with what is there and develop it." Bilbao bases her designs on the local craftsmanship and not on an exalted, set form. "Architecture is based on communication. To explore the local conditions, we have to talk a lot to people," says the architect, who naturally combines traditional motifs of Mexican architecture with contemporary expressions.

Early on in her career Bilbao had contact with a rich and famous family in Monterrey who had engaged architects Ricardo Legorreta, Tadao Ando and Herzog & de Meuron for the design of a new upscale residential area. Bilbao developed a house there as well, one that exploits its hillside location and picturesque views of the landscape. The Los Terrenos villa in San Pedro Garza Garcia, built in 2016, is organized around a patio. Simple terracotta tiles were used in the design of perforated screens that are both tasteful and useful. The rooms resemble small cocoons; the only truly generous space is the empty center offering views into the surrounding oak forests.

Bilbao's magnum opus, however, is the botanical garden in Culiacán in northwestern Mexico. For many years she has been designing pavilions, details and a path that skillfully combines interior and exterior spaces. Another promenade architecturale is the Ruta del Peregrino pilgrimage route of one hundred kilometers, which winds through the mountainous terrain in Jalisco north of Guadalajara. Bilbao’s contribution to that project is an open chapel where archaic, white concrete walls form a sacred space and its individual parts have been moved apart to frame views into the landscape.

Bilbao’s self-proclaimed mentor, Swiss architect Jacques Herzog, sees her as a (possible) "activist" who uses the social reality and visual culture of Mexico "as a resonator" and amalgamates it with cosmopolitan perceptions. Like Shigeru Ban and Alejandro Aravena, Bilbao takes on social responsibility. If architects want to remain relevant, they must at least reflect social problems in their designs, she claims, "in the era of self-interest." But her approach is aesthetic, not just sociological: Bilbao wants beauty for everyone. “Everyone has the right to beauty," she says. Kjeldsen even calls Bilbao a "Robin Hood architect" who takes from the rich (in fees) to design her social projects. How true this thesis is remains unclear.

Bilbao discovered the lower end of the residential architecture spectrum in Mexico when she was a staff member of the Construction Ministry in the late 1990s. In Mexico, there is a constitutional right to housing; that’s why the government produces millions of tiny houses without the help of architects. They typically are only 43 m2 in size, but Bilbao managed to increase the space to 60 m2 with just a few design tricks. Simple concrete stones and adobe bricks were used to build a maisonette with sleeping quarters tucked away over kitchen and bath, while covered outdoor space expands the living space.

In 2015, when a tornado struck the city of Acuña, awful garage-like blocks were quickly built. Bilbao cleverly rearranged 16 of these houses to provide more visual privacy and yet allow space for generous terraces. For the design of the villas, she arranged four rooms as a "cluster of pavilions" in a windmill form around a central courtyard. This trick, which has a scale effect on the villas, also creates a patio that can later be extended into a room. This project and others on display at the Louisiana Museum show Bilbao are not revolutionary; she seeks and uses the possibilities of reality. Her patience and perseverance show that an architect’s imagination can improve the welfare of all people, including the poor. “For a profession struggling to regain its moral compass,” as critic Nicolai Ouroussoff has described it, that's no small feat.

The Architect's Studio - Tatiana Bilbao Estudio is on display until April 5, 2020, at the Louisiana Art Museum in Humlebæk, Denmark.