OMA in 1989: Review of 'Project Without Form'

In Project Without Form: OMA, Rem Koolhaas, and the Laboratory of 1989, ZHAW professor Holger Schurk delves inside the Office of Metropolitan Architecture when it was working on three competition submissions in one year. OMA has not been the same since.

Rem Koolhaas was one of seven architects gathered by Philip Johnson and Mark Wigley for the influential and somewhat infamous Deconstructivist Architecture exhibition on view at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in the summer of 1988. The single project by Koolhaas and OMA - Office for Metropolitan Architecture included in the exhibition and catalog was Boompjes, a slab-like high-rise for Rotterdam that was commissioned in 1980 but remained unbuilt (the later De Rotterdam, built in 2013, can be seen as a 21st-century version of that earlier project). The fragmented nature of the high-rise and the Constructivist design of the companion bridge no doubt made Koolhaas and OMA a fitting addition to the exhibition in the eyes of the curators, who linked the philosophy of Deconstruction with Russian Constructivism. One year later, in the "Laboratory of 1989" in OMA's Rotterdam studio, things would explode, with the office working simultaneously on three competitions — Très Grande Bibliothèque (TGB) in Paris, Zeebrugge Sea Terminal in Belgium, and Zentrum fur Kunst und Medientechnologie (ZKM) in Karlsruhe, Germany — whose designs Holger Schurk collectively describes as "Project Without Form" in his new book of the same name.

Based on his dissertation at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna that was undertaken between 2013 and 2018, Project Without Form was published in German, as Projekt ohne Form, in 2020 and then released two years later in English. It arrives at a time when Rem Koolhaas's involvement in projects at OMA is minimal, with the other partners — Reinier de Graaf, Ellen van Loon, Shohei Shigematsu, Iyad Alsaka, David Gianotten, Chris van Duijn, Jason Long — directing the projects and being credited appropriately in press releases and on the firm's website. Still, their current work can be seen to fit within an approach dictated decades ago by Koolhaas; an approach that was arguably worked out most fruitfully in 1989. This is especially true of the TGB project, which OMA did not win but influenced many architects and architecture students — and pushed many of them to actually pursue jobs at OMA. Schurk's book examines the designs of the three projects, focusing primarily on TGB; at its deepest, the book is a portrait of a practice grappling with process and representation.

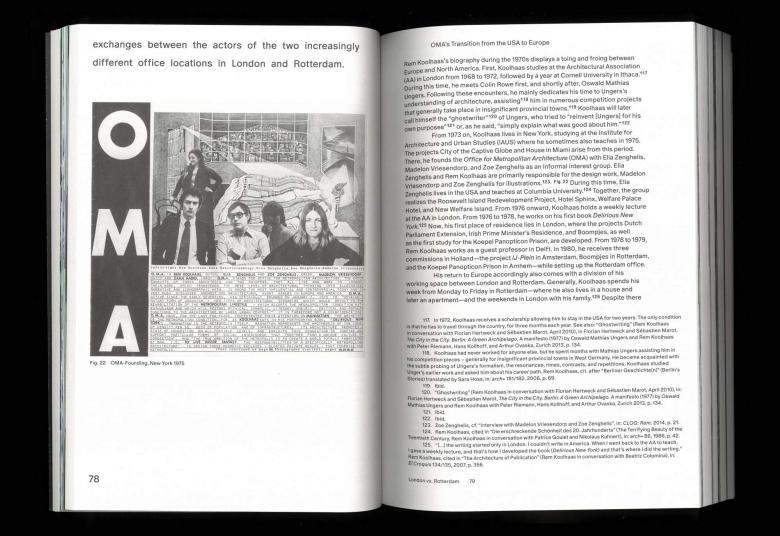

The first of the four chapters in Project Without Form is a prologue to the Laboratory of 1989, as Schurk calls it. Here readers learn about the influence of Russian Constructivists on Koolhaas, the theories in his 1978 book Delirious New York, and some familiar projects from his early years, but they also gain an understanding of some practical aspects of OMA, such as how Koolhaas and the other founding members (Elia Zenghelis, Madelon Vriesendorp, and Zoe Zenghelis) worked in London and Rotterdam (and eventually how they split up), Koolhaas's involvement with the Utopia group in Rotterdam, and the make-up of the studio leading up to the Laboratory of 1989. Even though Koolhaas's name is often used as a stand-in for OMA in the broader media, as if he controls every aspect of every project stamped with those three letters, it is apparent early in Schurk's book that the contributions of others in the office and their interactions with Koolhaas are integral to how OMA projects take shape.

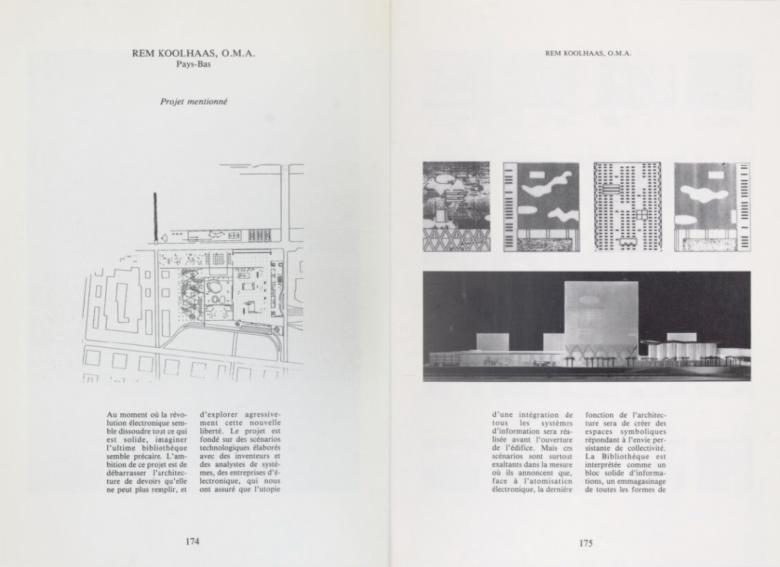

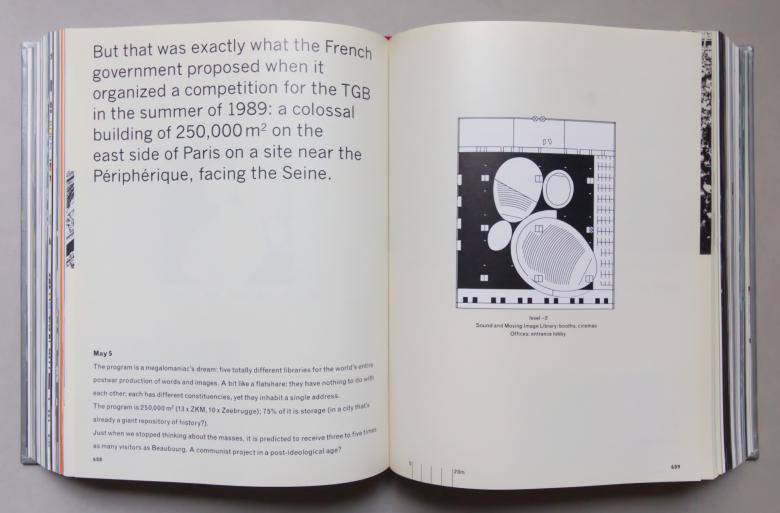

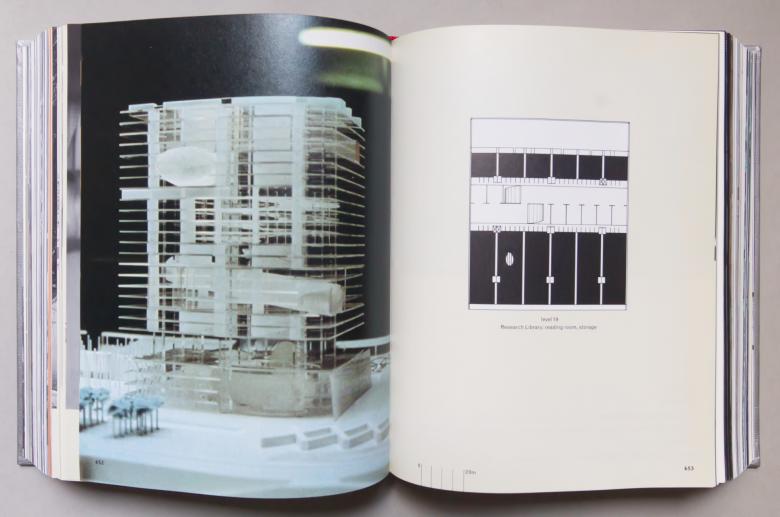

The second chapter, "The Laboratory of 1989: The Simultaneous Work on the Projects Zeebrugge, ZKM, and TGB," is — for good reason — the longest of the book's four chapters. Although it spells out the trio of competition entries being worked on that year, the focus is clearly on TGB, and as such the case study of its design process in this chapter is fascinating. Many people know OMA's design for the Très Grande Bibliothèque from S,M,L,XL (more on that later), but how did Koolhaas and his compatriots at OMA end up with a design so iconic? The resulting "voids" cut into floors of "solid" stacks evolved through sketches and drawings, not surprisingly, but the cubic form of the library — really five libraries in one, per the program — was there early on, the result of the architects addressing functional considerations but also how to accommodate so many square meters on a single site. Dominique Perrault's winning design put the books in four towers at each corner of the rectangular site, linking them underground and putting a landscape in the center, but Koolhaas and OMA allowed the program to push them into uncharted territory, both in terms of form and representation.

The remaining two chapters jump forward from 1989, highlighting the "Reception and Repercussions of the Laboratory of 1989" in chapter three and the subsequent evolution of OMA's "Project Without Form" in chapter four. Two productions following the TGB competition — both coinciding with the economic downturn at the beginning of the 1990s that greatly affected architects, including OMA — stand out from the rest: the Energieen (Energies) exhibition at Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam in 1990 and the publication of S,M,L,XL in 1995.

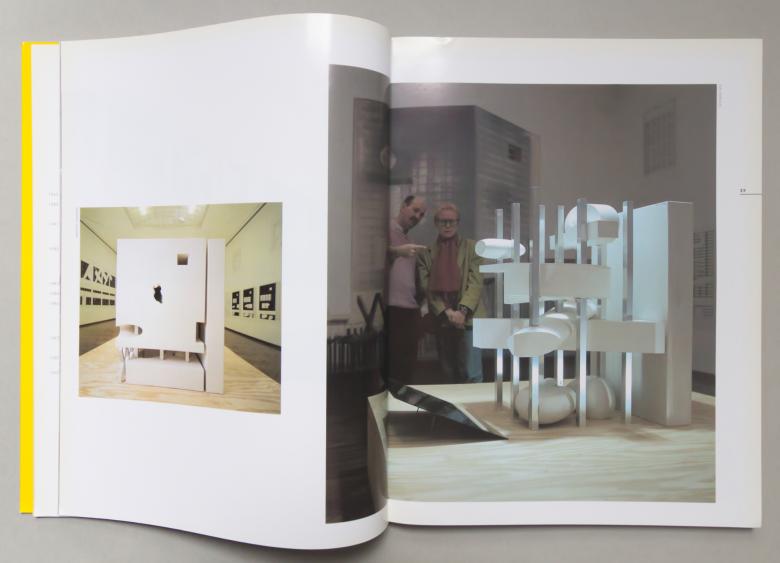

The Energieen group exhibition, curated by Wim Beeren, gathered prominent artists and designers, including Jenny Holzer, Bruce Nauman, Issey Miyake, and Cindy Sherman, but Rem Koolhaas was the only architect among them. Just as Deconstructivist Architecture exhibited just one OMA project, so did Energieen. Koolhaas used the opportunity to explore the representation of the TGB, particularly in model form. Instead of rebuilding the illuminated plexiglass model made for the competition, the studio of Parthesius & de Rijk fabricated two large plaster models, one concealing the programmatic spaces as voids within the solid stacks, and one expressing the program spaces as objects supported by nine cores. The latter, free of floor plates and therefore expressing an abstract idea more than an actual building design, became the most iconic image of OMA's TGB project.

S,M,L,XL was published five years after Energieen, but its planning started in 1992, when Koolhaas, designer Bruce Mau, and editor Jennifer Sigler begin the process of sifting through "a mountain of material" documenting "a work phase lasting more than ten years," in Schurk's words. Like the trio of projects in 1989 that were cumulatively a "Project Without Form," the massive book became a means of demonstrating "how to destroy and then rebuild architecture." While many of the sketches, drawings, models, and renderings from both the competition entry and Energieen exhibition are carried through to the 59 pages of TGB documentation in S,M,L,XL, the graphic treatment is decidedly different, eschewing the straightforward gridded presentation of floor plans and sections, for instance, in favor of sporadic drawings (one per spread, basically) accompanied by other images and text. Falling in the "L" chapter that notably includes Koolhaas's "Bigness, or the Problem of Large" essay, the lengthy documentation of the TGB finds Koolhaas theorizing one one component of the Laboratory of 1989 at a time when few comparable projects were in the office.

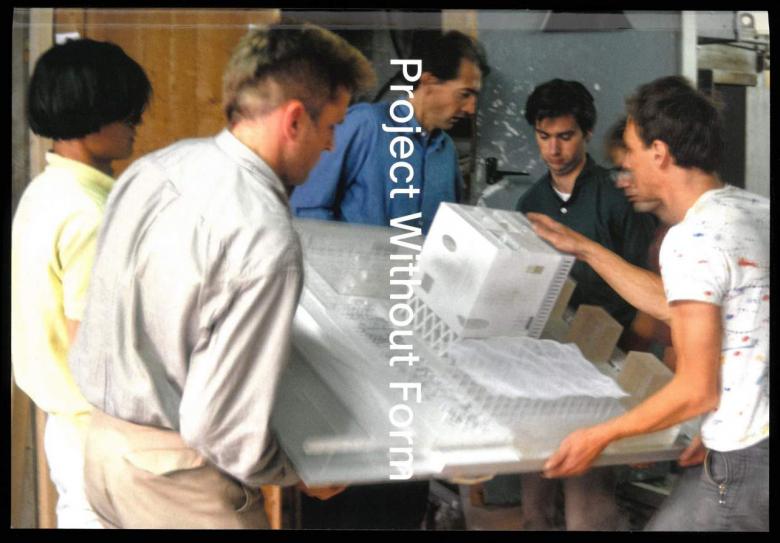

Perhaps realizing that a book about OMA needs to take some strides toward graphic innovation, Project Without Form is a striking object that alternates the four chapters and back matter (all b/w images and text on matte paper) with five sections that feature full-bleed color images on glossy pages. The first four of these are stills from artist Claudi Cornaz's footage of the OMA studio shot between 1986 and 1989, when he wore a crazy-looking custom helmet-camera and roller skated around the office. Candid images of Koolhaas talking on the phone, among other mundane things, are in abundance in the footage. The fifth visual section features color photographs of models being made for the TGB competition in 1989 and the Energieen exhibition in 1990 (the cover image is one such photograph). Combined, the five color sections elevate the importance of practice over theory in Schurk's case study of one year at OMA.

Project Without Form is the latest addition to a growing list of books that critically examines the output, thinking, and working process of Koolhaas and OMA. Previous books in this vein include: What Is OMA: Considering Rem Koolhaas And The Office For Metropolitan Architecture (2004) edited by Véronique Patteeuw; Made by the Office for Metropolitan Architecture: An Ethnography of Design (2009) by Albena Yaneva; Six Canonical Projects by Rem Koolhaas: Essays on the History of Ideas (2015) by Ingrid Böck; and OMA/Rem Koolhaas: A Critical Anthology from Delirious New York to S,M,L,XL (2019) by Christophe Van Gerrewey. (I cannot think of another living architect given such attention.) Schurk's book benefits from extensive interviews with architects who worked at OMA in 1989 (Georges Heintz and Xaveer De Geyter, among them), a deliberate focus on one of OMA's most iconic projects, and a graphic layout that is visually appealing, but it suffers from an English translation and copy editing that is substandard in a number of places. This is an academic text, so it should not be an easy read, but it also should not be needlessly frustrating to the reader; one more pass of editing should have done the trick. Readers of German should opt for Projekt ohne Form, but English readers should ready themselves for an at-times nettlesome text on a fascinating and (still) influential project.

Project Without Form: OMA, Rem Koolhaas, and the Laboratory of 1989

Holger Schurk

19 x 27 cm

450 Pàgines

Paperback

ISBN 9783959053754

Spector Books

Purchase this book