On the Death of Nikolaus Kuhnert (1939–2025)

Architectural Criticism As a Tool

Nikolaus Kuhnert played a decisive role in shaping German architectural discourse for decades: From 1972, the critical mind was part of the editorial team of the magazine ARCH+, founded in 1968, of which he became co-editor in 1982.

I got to know Nikolaus Kuhnert in 2003 through Günther Uhlig (1937-2021). The latter had invited me to edit an issue on urbanization together with the team of ARCH+. We discussed the topic, which Kuhnert, who was not really keen on the developments in China, viewed with great skepticism. Issue 168 of ARCH+, titled Chinesischer Hochgeschwindigkeitsurbanismus (Chinese High-Speed Urbanism), was finally published at the beginning of 2004. I worked with Uhlig, Kuhnert, and Anh-Linh Ngo as the editorial team for the magazine.

Nikolaus Kuhnert was born in Potsdam in 1939. His mother was Jewish, his father Catholic, which is why the ruling National Socialists labeled him a so-called “half-Jew.” Many of his relatives died in the Holocaust, and he himself grew up highly endangered as a child, which connected him to the slightly older (later) Berlin architects Peter Pfankuch (1925-1977) and Georg Heinrichs (1926-2020), both of whom were pushed into forced labor as teenagers because of their Jewish mothers.

After the war, his father returned from the labor camp and initially stayed with the family in the Eastern zone, which was formed into the GDR in 1949. His father then went to West Berlin, where he was able to run his own architectural practice. The family followed in 1953. After graduating from high school, Nikolaus Kuhnert decided to study architecture in West Berlin at the Technical University, which had been newly founded in 1946. He remembered his studies as boring, and around 1960 he worked with fellow students in his father's office on designs for detached houses, which were also realized.

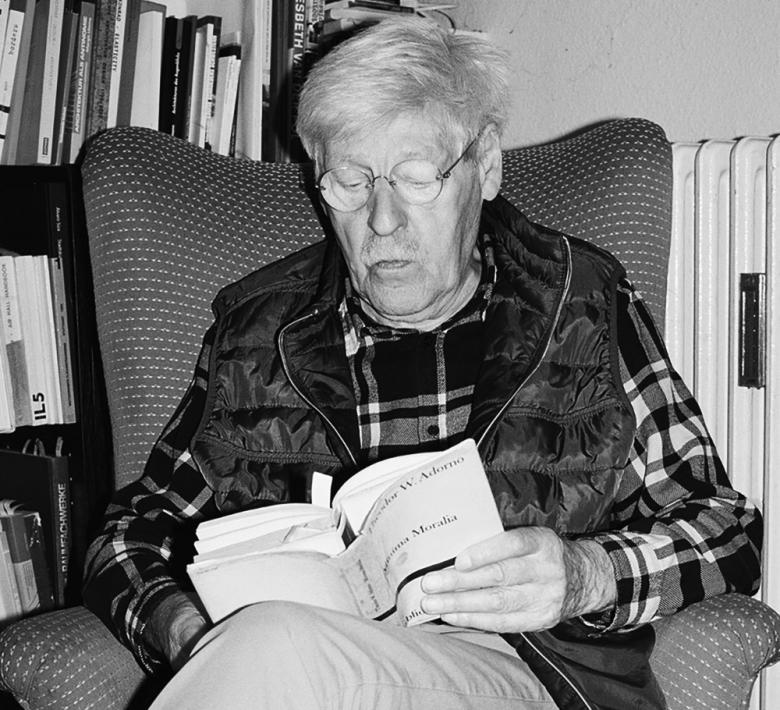

During this time, Hans Scharoun was a role model for him, whose position he saw as the basis for further development. At the university, Kuhnert missed the critical examination of the building process, as the focus was on making things. A new phase began for him in 1966, when political discussions began in other departments, which also shed new light on his unanswered questions about architecture. The student movement was forming, the fascination for the critical theory of Adorno and Marcuse, social theory, history and sociology came into focus. In 1970 Kuhnert presented his diploma at the TU as a theoretical thesis on communitarianism. Between 1972 and 1983, he worked at the Chair of Planning Theory at RWTH Aachen University, where he completed his doctorate, in 1978, with a thesis entitled “Social Elements of Architecture: Types and Concepts of Type in the Context of Rational Architecture.”

From 1972, Kuhnert worked on the editorial team of ARCH+ and ten years later, together with Sabine Kraft, Günther Uhlig, and Marc Fester, formed the editorial team of the quarterly magazine, which then had editorial offices in Aachen and West Berlin. ARCH+ subsequently developed into a seismograph for the state of architecture in the context of its social significance. As a critical spirit and independent thinker, Kuhnert stimulated new discourses that were oriented towards his personal interests on the one hand and made international trends accessible to the German readership on the other. He repeatedly pursued individual people or positions, even if this required several issues. Between 1979 and 1983, for example, ARCH+ published five issues of Julius Posener's “Lectures on the History of New Architecture,” which have been reprinted several times to date.

In the early 1980s, the magazines dealt with alternative living and housing models, squatting in Berlin, and the question of how local and regional solutions could lead to an ecological and sustainable economy in the construction sector. To this end, they looked at history, compared developments outside Germany, and began to translate important texts from other languages into German. On the subject of regional building, which was to be detached from the conservative and National Socialist contexts in a broader discussion, ARCH+ published, for example, the construction primer for Lorraine by Emil Steffann, who had formulated the ideas in 1943 during National Socialism, which appeared here in printed form for the first time. The topic was embedded in a critical discourse on regionalism under National Socialism and in the conservative circles around Paul Schultze-Naumburg during the Weimar Republic. The topic of ecological and landscape-bound construction (issue 81/1985), as well as earth building (issue 80), timber construction (issue 82), and building with stone (issue 84), was discussed in the mid-1980s in the context of sustainable solutions.

At that time, texts on Christopher Alexander's A Pattern Language were also published in German translation (issue 73/1984). Thematic issues on marginal personalities such as Hugo Kükelhaus (issue 78/1984), who dealt with the sensory perception of the living environment, were also developed. This was followed by themed issues on developments in America and deconstruction, as well as issues on individuals such as Reyner Banham (issue 93/1988) and the designer Otl Aicher (issue 98/1989), who gave the magazine a new look during this period, which remained a defining feature until 2008. Further issues focused on the philosopher Vilém Flusser, Oswald Mathias Ungers, and, in the 1990s and 2000s, Rem Koolhaas. Anyone looking back through the old issues will always discover surprising aspects that in one way or another relate to his own experiences and document what seemed important to him at the time.

To mark his 80th birthday, ARCH+ published Nikolaus Kuhnert: Eine architektonische Selbstbiografie (An Architectural Self-Biography), in which Kuhnert's personal life and his work as a long-standing editor of the magazine can be read. In retrospect, the focus of the debates conducted in ARCH+ makes it clear that the editorial team continually brought seemingly marginal topics, people, and aspects of a changing professional practice into focus, thereby taking the debate beyond the confines of the narrow specialist community. Nikolaus Kuhnert and the ARCH+ were often somewhat ahead of their time, raising important questions that affected the core of cultural self-image and had an impact on society as a whole.