An Interview About ‘Intelligens. Natural. Artificial. Collective.’

Redefining Boundaries with Carlo Ratti

World-Architects spoke recently with architect, engineer, author, and educator Carlo Ratti via Zoom, to discuss his plans for the 2025 Venice Architecture Biennale and parse the theme — Intelligens. Natural. Artificial. Collective. — that he has defined for the exhibition. Our conversation took place about a month after the theme was announced and just a few days after the “Space for Ideas” open call for proposals closed.

Carlo Ratti was selected as curator of the 19th International Architecture Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia in late 2023, exactly 18 months ahead of its opening in May 2025. At that time we could only speculate on what Ratti — head of his eponymous practice in Turin, director of the Senseable City Lab at MIT, a prolific author of architectural publications, and an inventor — would determine as a theme for contributors to explore. Then in May of this year, Ratti and first-term Biennale President Pietrangelo Buttafuoco revealed the Biennale Architettura 2025 theme: Intelligens. Natural. Artificial. Collective. In short, the theme will solicit proposals with intelligent solutions for pressing problems, “exploring a definition of ‘intelligence’ as an ability to adapt to the environment with limited resources, knowledge, or power.” The various designs — ranging from objects to buildings to urban plans — would be organized along “the axis of a multiple and widespread intelligence”: natural, artificial, collective, and various combinations of the three. With an acknowledgment of the importance of addressing climate change, an openness to fields outside of architecture (art, engineering, biology and other sciences, etc.), and Ratti’s predilection for bottom-up approaches in architecture and urban design, the theme both overlaps and departs with recent iterations of the Venice Architecture Biennale. Our conversation about Intelligens is lightly edited for length and clarity.

John Hill (JH): First, how does the Intelligens theme relate to your work, be it in your studio, your writing, and the Senseable City Lab at MIT?

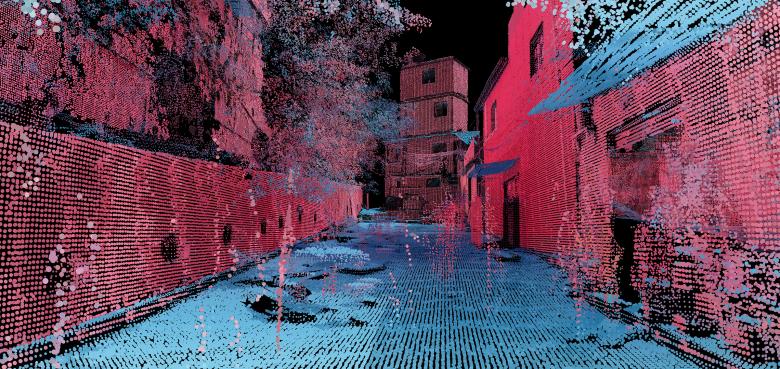

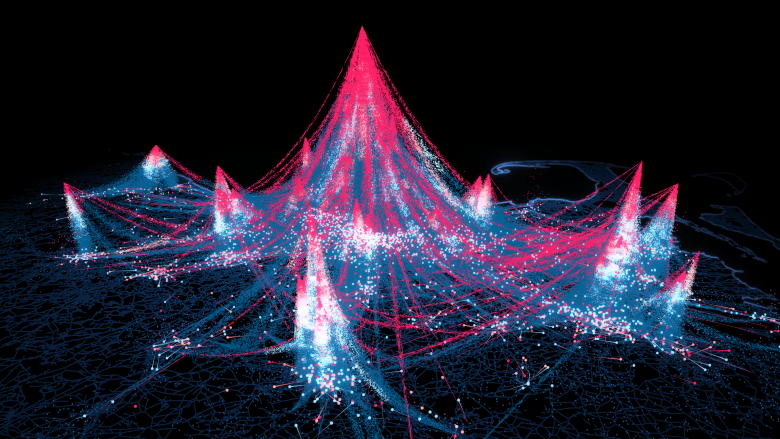

Carlo Ratti (CR): Well, at MIT, we started at the very beginning. We were connected with the Media Lab, and the type of intelligence there around 20 years ago really dealt more with network sensors, artificial intelligence, and so on. But then after a few years, the Senseable City Lab started looking at the broader aspect of things. Some of the latest projects deal with biology and also with collective intelligence. Even if we started more with digital intelligence — call it artificial intelligence, the idea of artificial networks blending with our cities — little by little the other dimension started to become part of the picture. It is similar to what also happened with our design office. Today, as everybody is focused on just on a uni-dimensional definition of intelligence, on artificial intelligence and ChatGPT, we thought it was important to go back to this deeper, more inclusive definition. The title is a single title for both Italian and English using the Latin root, and the end of the title, the end of Intelligens — gens — means people, means collective. We like this idea that we should have a more holistic, multiple view of intelligence.

JH: Do you see the theme as building on the issues you explored in pieces like Open Source Architecture, the book you wrote with Matthew Claudel in 2015?

CR: Absolutely. That book explored the notion of collective intelligence. If you look at the book, it focuses on the collective, but it also has a component that's related to networks. It is a combination of the two, but mostly the collective component, how we can together shape the built environment. But if you look at another book we did at more or less the same time [The City of Tomorrow: Sensors, Networks, Hackers, and the Future of Urban Life], it looks more at data and other types of intelligence. We could go book by book, but there are different ways to look at how there is more than one intelligence. The one we just discussed is probably mostly about collective intelligence in building cities — it goes back to Chris Alexander and many others — but it also looks at how new digital networks can enhance it. So, again, it is this kind of multiplicity of intelligence.

JH: With my reading of theme when it was released in May, it sounded a bit like the work of architects is not as important as that of non-architects. (Architects are not responsible for a large percentage of buildings, so this is not shocking.) But I’m curious what you see as the role of architects in a world where technologies, be it AI, or ideas like open source architecture, architecture without architects, etc., have more potential to address crises than architecture. What is the architect's role in the future?

CR: I think architects can have a crucial role. If you look at what's happening in the US today, if you look at polls and statistics, you know that most students actually experience climate anxiety. They're very concerned about the planet, the climate. When you look at scientific data, you see that the trajectory might be more concerning that what we thought a few years or ago or just last year. At the same time, if you look at enrollment in architecture schools, it is going down. It is almost like a paradox, because living together in a more sustainable way — designing better cities, designing better buildings — is the only thing we can do to face the climate crisis.

I would say that architecture can be a linchpin in addressing these issues and that is one of the things I hope people would take away from the Architecture Biennale. There's a missing link: people are very concerned about this, but they don't see the architectural resolution. Architecture, in a broader sense, is really about shaping how we live — in our cities, our buildings, and so on — and so it can be a pivotal player. At the same time, clearly we are not alone, so we need to look at other disciplines, not only traditional ones like engineering, but hard sciences, social sciences, and many others in order to work together. Again, I would say architecture can be at the core of it, and that's one of the messages I hope people will take back home from the upcoming Exhibition.

JH: In regard to people taking away messages from the Architecture Biennale, I think a criticism often levied at architecture exhibitions is that they come across as architects speaking to other architects; that the general public has a difficult time in understanding what is being presented. I'm curious how you're approaching “audience” with the exhibition. What are you defining as the audience? Who will you be speaking to?

CR: So we just talked about one audience — the people going to universities today and trying to make architecture be the solution. If you look at architecture departments today, you see different camps; there are many people looking at different types of intelligence and not talking to each other. People looking at “green” don't talk with people looking at “smart” who don't talk with people looking at collectives. In most architecture schools globally, you see people looking at these different aspects, but they don't collaborate much. I'm simplifying a little bit, but it is basically these different camps.

If you think about [Marc-Antoine] Laugier, architecture begins when the climate is adverse. If there is no adversity outside, no need to protect ourself from the rain, the heat, the cold, and so on, then you almost don’t need architecture. With Laugier, that was the beginning of architecture, but in the face of a climate that might become more difficult and more hostile, blending these different types of intelligence is how we can find better way forward. And what is behind all of those approaches is, again, something very similar: intelligence. Natural, artificial, and collective are what binds together the different units in every architecture school.

Of course, there is a second audience, of practicing architects; I think you still want to talk to architects. There is a beautiful exhibition I just saw a few days ago at the Pavillon d’Arsenal in Paris, Urban Natures curated by Antoine Picon. In the catalog, he makes the point that “smart” and “green” are two things that are converging. More and more people are realizing that.

But the third aspect, as you said that is very important, is that this is something that concerns all of us; about shaping the environment and making it more sustainable. We would love to get an audience of a billion people — and that is about going beyond the architecture community — so we're looking at different ways to achieve that. Clearly it is not just about attracting people to Venice, but engaging people in different ways. For this we are trying to mix a top-down approach with an open, bottom-up approach. There was an open call, which just closed, and we received a huge number of proposals. That is one way to engage a diverse audience.

JH: Alongside the “Space for Ideas” open call, I assume that, as curator, you’re finding contributors that you think fit the Intelligens theme. What do you have in mind for them?

CR: It is very interesting because we are running all of them through the same database: the Space for Ideas, other people sending out things, and so on. It's a multiplicity of inputs, but they all go through the same kind of bottom-up selection process. We want to collect every voice; everybody counts and we want to have as many channels as possible to hear from them.

JH: I just finished Open Source Architecture, and in it you define “the Choral Architect,” a figure who transforms multiple inputs from many people into a buildable design. Would you say that your role as curator of the Architecture Biennale is akin to the Choral Architect?

CR: The Choral Architect is about orchestrating multiple voices, but that is more about architecture. When you are curating something, by definition you are more choral, like a harmonizer, taking different voices and so on. The book goes beyond that because it says the architect’s role is a choral role even when you're doing a building or something else. But certainly in the case of the Architecture Biennale, in a curation role, that is key.

JH: In terms of the actual Architecture Biennale taking place, the Central Pavilion being closed for renovation next year leaves the Arsenale as the only typical venue for you to work with. How will your exhibition be expanding into other parts of the city, and how are you handling the logistics of this?

CR: The Central Pavilion is under renovation because La Biennale di Venezia was successful in getting funding from a nationwide post-Covid program that allows it to refurbish many buildings, including the Central Pavilion. I remember the first time the team from the Biennale came to me and said, “Well, we have a problem, because we don't have the Central Pavilion.” I think I’ve spent enough time in the United States that I replied, “It's not a problem, it’s an opportunity.” The opportunity is that we can do something else. We are thinking about how to take what would be in the Central Pavilion and basically spread it throughout Venice. That is what we are doing with a number of special projects, taking some of the themes of the three types of intelligence: some of them will be at the Giardini, some of them at the Arsenale, some of them outside of both.

There was a book we did with Manifesta last year. Manifesta is one of the large biennials, moving from city to city every two years. A few iterations ago, they started to involve architects and planners to prepare an urban study for the city. The first one was by OMA in Palermo; the second one was by The Why Factory and MVRDV in Marseilles; and we did a third one in Prishtina. By doing small things there, even temporary things, we are able to generate long-lasting change. And that, again, becomes a very interesting way of encouraging community participation. The Manifesta book that we made goes a bit beyond Open Source Architecture, by basically doing small, temporary things that people could then engage with at different levels. Some people could engage at a design level, but some people could just work with their feet, by going there.

We want to do something similar in Venice. A lot of people going to Venice — starting with [John] Ruskin, in 1848, with The Stones of Venice — have been thinking about how to “save” Venice. Given that Venice is probably the most fragile city on the planet in the face of a changing climate, we want to use Venice as a lab to look at how we design, exploring how it can save other cities instead. Some of these special projects will deal with the edge between the land and the water, with water purification, with new and innovative ways to produce energy. Since in Venice you cannot do things in a traditional way, such as with photovoltaics on the roof, we want to use Venice as a lab to try out new architectural ideas. That is what will take the place of the Central Pavilion.

All of this requires additional logistics and additional funding as well. We are trying to find supporters for these special projects, but with the support of the Biennale team it looks like we are managing to achieve that.

JH: As a last question, how do you see your exhibition and the Intelligens theme fitting into the previous architecture Biennales? Is it even important to you that they relate in any way?

CR: Yes, I think it's important. If you look at the perimeter, the boundaries of architecture, they have changed a lot. If you look at Vitruvius and then you go to the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, and all the past treatises of architecture, the boundaries of architecture have changed. The same thing happened with some of the past Architecture Biennales, which I have enjoyed very much, some of them moving more into the arts or into politics or other directions. The important thing is that every Biennale International Exhibition has to relate to a boundary but also take a theme and focus on it in full. And that is what we’re trying to do: to push the boundary in a different direction, but not as an opposition; it is actually an enrichment, because you’re looking at how this boundary keeps being redefined. I think the role of the Biennale is to take one direction and push the boundary, so as to enrich this kind of constant redefinition of the perimeter that will continue to change as we move forward.

Articles liés

-

-

-

-

Isabel Zumtobel: 'We Believe in the Power of Design to Change the Future for the Better'

World-Architects Editors | 18.11.2025