A review of Victor Kossakovsky's 'Architecton'

From the Quarry to the Garden

Architecton is the third installment in Victor Kossakovsky's “A” trilogy—following Vivan las Antipodas! (2011) and Aquarela (2018)—which finds the Russian filmmaker exploring humanity's place on the Earth. The 2024 documentary oscillates between hypnotic slow-motion sequences of quarry blasts and concrete production, black-and-white images of architectural ruins, and architect Michele De Lucchi creating a small piece of land art at his Italian home.

Why Michele De Lucchi? Why is an Italian architect and industrial designer known more for designing lamps and chairs than buildings the face of Architecton? This question was at the forefront of my mind before and as I watched the documentary a week ahead of A24 releasing it in the United States this Friday. Architecton tackles big subjects—concrete and carbon pollution, ruined civilizations, war and destruction—all expressed in poetic yet aggressive images accompanied by equally impressive sounds and music rendered in Dolby Atmos.

Yet, between the slow-motion rock slides, steel teeth grinding up stones, scenes of destruction in Ukraine and Turkey, and dozens of trucks lined up to dump rubble into a landfill are idyllic scenes of De Lucchi—hermit-like with his long gray beard, long brown coat, and wide-brimmed hat keeping the rain and snow off his face—directing two stonemasons to inscribe a circle in his lawn. The scale of De Lucchi's creation is minuscule, insignificant compared to that of the environmental and physical destruction portrayed throughout the rest of the film. As the only architect in a film about the way humans are harming the Earth through the production of buildings, De Lucchi's presence is a bit of a conundrum.

One answer to my question can be found by going back to 1973, when De Lucchi was a 22-year-old student at the University of Florence. Together with some classmates he founded Cavart (“quarry art”), a collective that promoted ecological awareness, democratic participation, and a more human approach to design. Their favored venues were stone quarries, where they would stage workshops, performances, and installations. “We chose the name Cavart because we wanted to design,” he told Domus in 1999, “but not so much by adding one thing to another, houses to the houses, condominiums to condominiums, but by paring them away, so it was like quarrying, the quarry was a sort of metaphor for removal.”

Cavart's first event was held in the quarries of Mount Lonzina at Luvigliano, near Padua, in July 1973. Their most famous event, a seminar titled “Culturally Impossible Architecture,” took place two years later inside an abandoned quarry at Sonta Rosa on Mount Ricco, near Monselice, when around a hundred students, artists, and architects spent a week erecting installations. “All showed the same stubborn desire to dismantle the architectural models that imprison mankind within the standard patterns of everyday life,” wrote Alessandro Mendini in coverage in Casa Vogue. Most of the installation were small, but De Lucchi's contribution was full-size: a 10-meter-tall “vertical house” made from scaffolding, wire netting, and household fixtures—but no floors. The single occupant would climb the structure and reposition the fixtures (stove, bathtub, bed, etc.) as desired, recovering the bodily physicality that was “absent from man frustrated by Functionalism,” he explained at the time.

De Lucchi was involved in Cavart until it dissolved in 1978, the same year he co-founded Memphis and began designing objects that helped define Postmodernism—colorful mass-produced objects that can be seen as the antithesis of the ecologically minded Cavart group. While it's hard not to see the parallels between De Lucchi's early Cavart experiences and the many scenes of rock quarries that pepper Architecton, Kossakovsky admits the Italian architect stood out to him because, “among the most famous architects of our time” the director interviewed for the film, “[De Lucchi] was the only one with humility.”

Kossakovsky asked twenty otherwise unnamed architects two questions: "Why did you become an architect? And what should be the dominant focus of the modern city?" For the latter, De Lucchi “was thinking about open space—empty space— a circle where man cannot enter,” the director explained, “in order to remind us that Nature is at the center of our existence.” This empty space and De Lucchi's “[shame] of building drab rectangles in Milan, adding more concrete to a city that’s already losing its soul,” were enough to push Kossakovsky to make De Lucchi the “star” of his documentary.

See also: “Building on Screen,” our review of The Brutalist, another architecture-centric film from A24.

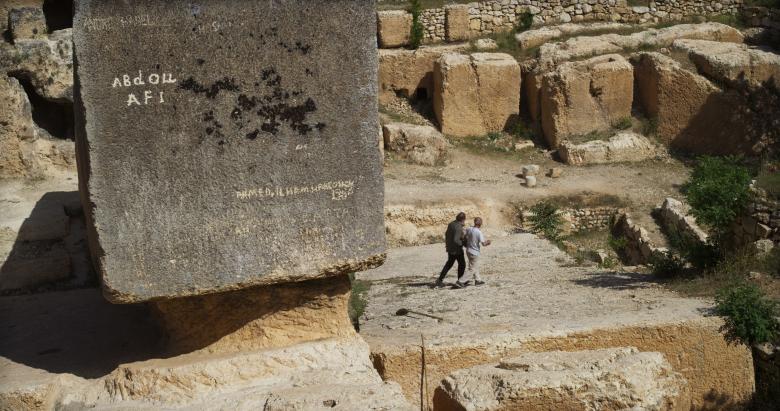

De Lucchi is not the only face in the film. In addition to Mauro Mella and Davide Alioli, the two stonemasons he works with, we encounter Abdul Nabi al-Afi, who preserves megaliths at a Roman quarry site in Baalbek, Maksim Gaubetc, a specialist on ancient ruins in the Middle East, and the director himself, who speaks with De Lucchi after his stone circle is done. Most closely aligned with De Lucchi though is Nick Steur, who creates site-specific installations that are durational and primarily made ouf of stone. We watch Steur delicately—and seemingly impossibly—balance rocks atop each other. Lifted to eye and camera level on steel stilts, the rocks eventually fall, caught by the artist as they move back to the earth after a few brief moments as parts of artworks captured on film. Steur's artworks are the gravity-defying inverse of the chaos in slow motion that is Kossakovsky footage of rock slides.

Kossakovsky's decision to include Steur in Architecton is as curious as De Lucchi's presence. After all, stone as an artistic medium brings to mind Michelangelo's David, Noguchi's abstract sculptures, the Moai statues at Easter Island, or other long-lasting creations, not ephemeral art. Some sense comes at the end of the film, when we see De Lucchi's circle of stone and nature completed: Like De Lucchi in his twenties, Kossakovsky wants to provoke a rethinking of architecture as well as the incessant need to build, especially out of concrete. In Architecton, this material is expressed through its ingredients, in the stone that is quarried from terraced mountainsides and then gradually broken down to sizes appropriate for aggregate; through its construction, as the liquid material is pumped atop 3D-printed walls; and at the end of its useful life, in the guise of concrete buildings destroyed by Russian missiles and a 7.8-magnitude earthquake in Turkey.

At its most basic, De Lucchi's circle implies a cycle—of civilizations repeating the same existential mistakes of resource exploitation and depletion. The fleetingness of Steur's balancing rocks echoes the fluted stones at Baalbek, the pieces that began as columns but are now strewn across the ground like litter. But today, in the third decade of the 21st century, the stakes are higher, encompassing the whole planet and the entire human race, not just one civilization. The energy-hungry, carbon-polluting status quo cannot hold. It's obvious that things need to change, but change is not happening—at least not at the pace and the scale for it to have an impact. Architecton is one man's plea to stop building in concrete, and another man's plea to put nature at the center of our lives. Together, Kossakovsky and De Lucchi have made a poetic and passionate appeal for reconsidering architecture and construction.

2024, 97 minutes

English and Italian with English subtitles

Written and directed by Victor Kossakovsky

Produced by Heino Deckert

A24 is releasing the film in the United States on August 1, 2025.