Down and Out(side) at Calder Gardens

The long-awaited grand opening of Calder Gardens—the new arts institution dedicated to the world-famous 20th-century artist Alexander Calder—takes place in Philadelphia on September 21, 2025. World-Architects got a peek of the Herzog & de Meuron-designed building and gardens by Piet Oudolf ahead of Sunday's opening.

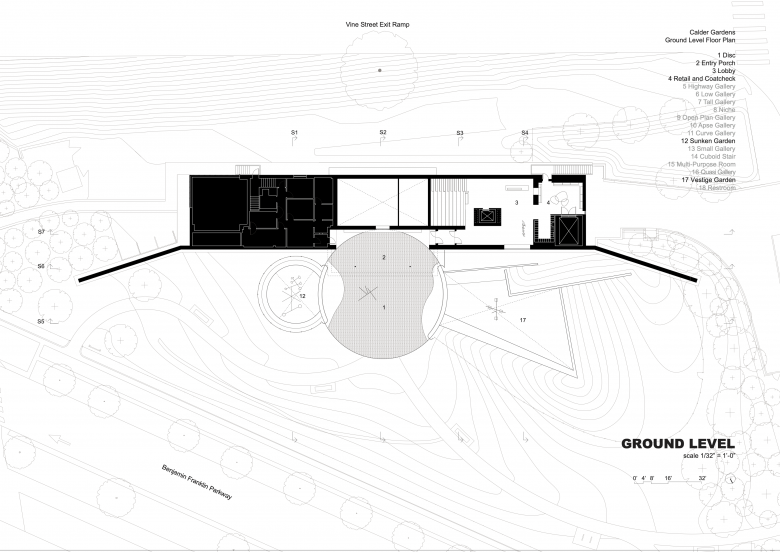

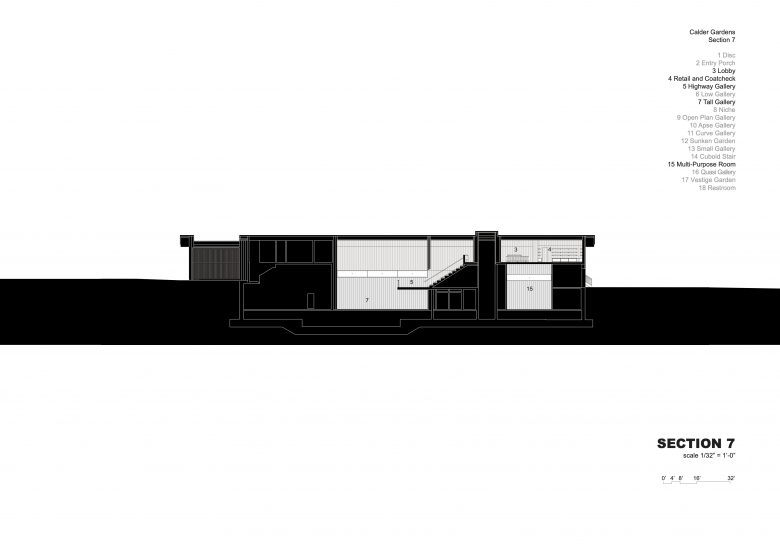

Most visitors to Calder Gardens will approach it from the north via Benjamin Franklin Parkway, the wide thoroughfare that cuts diagonally across the city's grid, from the Philadelphia Museum of Art by the Schuykill River to Philadelphia City Hall in the heart of City Center. Calder Gardens sits on a trapezoidal block between the early-20th-century parkway and the Vine Street Expressway, which follows Philly's grid but is a wide, sunken expanse that divided neighborhoods upon its completion in the mid-1960s. Herzog & de Meuron describes the site as “a leftover space without much obvious charm,” where “the sound of the highway is always present.” Suitably, the Swiss architects used a long tapered wall to divide the site into two, putting “a simple barn-like building” on the back side of the wall next to the highway, and placing the gardens designed by Piet Oudolf toward the parkway. The metal wall creates muted reflections of the gardens and the trees that line the parkway, beyond which sits the Barnes Foundation, which provides administrative and operational support for Calder Gardens.

Beyond the support it provides, the Barnes Foundation offers something of a precedent for the architecture of Calder Gardens and building astride Benjamin Franklin Parkway. In their 2012 design for the relocated collection of Dr. Albert C. Barnes from suburban Merion, Tod Williams and Billie Tsien conceived of the museum as “a gallery in a garden and a garden in a gallery.” The rectilinear two-story building sits within a public garden designed by Laurie Olin, and it features a tree-filled light well at one end and a covered outdoor terrace at the other end. Though large, with a monumental light box running the length of the building, the visitor experience is one of intimacy, due in large part to the art galleries being replicas of the original rooms at the Barnes estate in Merion.

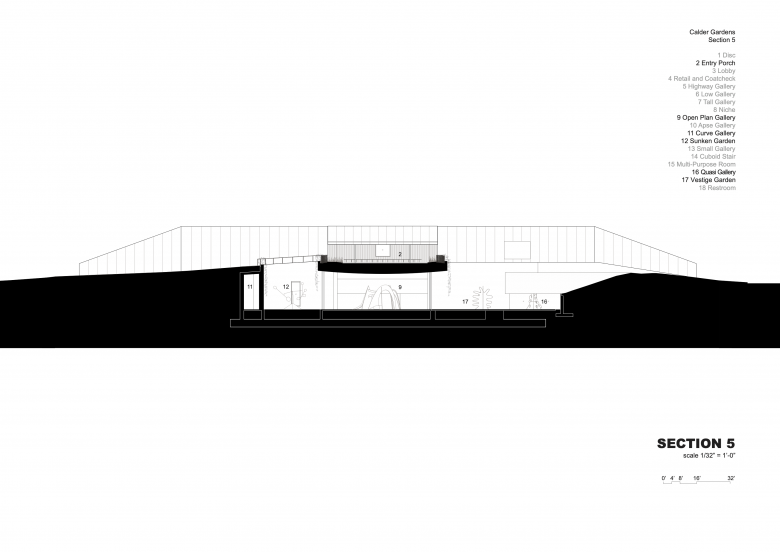

As assembled in a handsome coffee table book from Hauser & Wirth, one of the very first sketches by Jacques Herzog shows a vertical structure that rises above the landscape. Very quickly those “vertical stacks of fragments,” as he calls them, gave way to the idea that, Barnes-like, “gardens became a key element” and “not form but space should be the driving factor” in the display of Calder's artworks. “We turned away from this first approach and started to dig into the ground,” he explains, “excavating spaces of various sizes and shapes, with light from above and from the side.” These spaces reveal themselves to visitors as they approach the building—its entrance clearly signaled by what Herzog calls the “opening flap,” a metal roof shielding a wood-lined porch—and stand upon the large central “disc” that forms a plaza between two sunken gardens. Visitors immediately confront a Calder statue while standing on the plaza, though views of additional sculptures in the excavated spaces pique their interest and pull them inside.

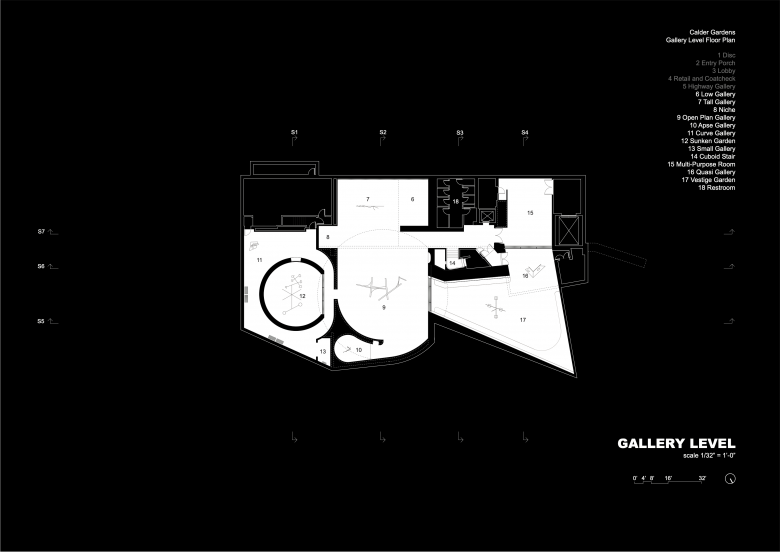

The movement through the Piet Oudolf-designed gardens, across the plaza, and under the opening flap is the beginning of what Herzog & de Meuron describes as a “nonlinear layout—a sequence of unexpected spaces that unfold and reveal themselves as visitors move through the building.” For able-bodied people, the winding path downward through the building reveals Calder's mobiles and other sculptures in carefully orchestrated glimpses, building up to the indoor and outdoor galleries on the lower level. The 180-degree turn through the lobby brings visitors to a small amphitheater with a narrow horizontal view to one of the underground galleries. The shape of this view is echoed at mezzanine level, called the Highway Gallery because its ribbon windows frame the Vine Street Expressway to the south. Opposite the windows, a slot of space above a long concrete beam hints at the main Open Plan Gallery that sits below the plaza.

The path downward takes another 180-degree turn, to a dark stair lined in what Herzog explains is nagelfluh: “concrete walls with rock aggregates that look like natural stone.” It is visitors' first, but not last, encounter with the material, but here the effect is simultaneously eerie yet exhilarating, because off the landing of the dark Cuboid Stair is a softly illuminated niche with a small Calder mobile. It is hard not to stop here and take a momentary pause in the building's architecturale promenade. Stepping off the stair and onto the polished concrete floor of the gallery level, natural light draws visitors to the left, toward the numerous spatially named galleries (Low Gallery, Tall Gallery, Open Gallery) and the appropriately sized artworks within them. Free of wall text or handouts, the formal aspects of the Calders and how they relate to the spaces take priority over historical, curatorial, or other meanings. Per the institution, the installations will rotate over time, such that “Calder’s art will come and go in waves: a slow process of change that encourages close looking and repeat visits.”

The disc shape of the plaza is evident at this lowest level in curved walls but also lines in the ceiling and overhangs at windows. While the generous space of the Open Plan Gallery beneath the disc would seem to be the culmination of a visit to Calder Gardens, views to the outdoors, streams of daylight entering the gallery, and hints of spaces around walls beckon one to continue. Clearly, as Herzog writes in the catalog of his sketches, the building “[allows] for the works of art to express their incredible diversity and ambiguity within numerous different spatial contexts.” The spaces that extend from the Open Plan Gallery include the dramatically top-lit Apse Gallery; the inaccessible Sunken Gallery and, surrounding it, the Curve Gallery that wraps to a niche with art by Calder's mother, father, and grandfather; the covered outdoor Quasi Gallery and, adjacent to it, the Vestige Garden, so named because it geometry is a ghostly reminder of the urban plots that predated the construction of the parkway.

The Vestige Garden is an outdoor space with walls of nagelfluh cradling a Calder sculpture in black steel. For me, it was a fitting place to wrap up my first visit to the intimate and surprisingly complex Calder Gardens. Earlier I had looked down to the sunken garden from the plaza above, knowing I wanted to go there. Yet, once I was at gallery level the route to it was subtle, almost hidden behind large wooden doors; it was only after seeing the other galleries that I found my way outside. This made me wonder, as I moved through the building, was I choosing the route or was the architect guiding me? Certain paths are predetermined but others are free—the former like Calder's steel sculptures and the latter like the movement of Calder's mobiles in a breeze. So, in an unexpected way, Herzog & de Meuron managed to design a building that taps into the spirit of Alexander Calder and provides wonderful spaces in which to experience his artworks.