'Ride,' a new monograph from Rizzoli

Six Decades of Antoine Predock's Architecture

Ride: Antoine Predock: 65 Years of Architecture is a new monograph from Rizzoli released this week on famed American architect Antoine Predock, who died last month at the age of 87. The hefty, nearly 700-page “memoirograph” traces Predock's highly active life and prolific career. Here we take a decade-by-decade look at some of the buildings presented in Ride.

First, why “Ride”? Simply put, Predock loved to ride; he was not shy about his love of motorcycles. There is a page on Antoine Predock Architect's website devoted to the many motorcycles he rode, and it is not difficult to come across online a photograph of him riding one of his motorcycles. One such photo is at the top of “The Ride,” the first of the two introductory essays he wrote for the book, where riding is also a metaphor. He would, for example, start a project by “jumping on it” and “taking a ride on it.” “With every project,” he wrote, “there is an attempt to digest and consume — to find, but not entirely burn up, the right kind of fuel.” He saw architecture as “an intellectual and physical ride [with] the thrill of a motorcycle on the open road.” He also believed people would interact with his buildings as “a ride,” but one that wasn't prescribed, that didn't have “a single way of encountering.”

Before readers come to the pages in the book with the buildings in his adopted home of New Mexico and in neighboring Arizona that brought him some attention and many more commissions, in a section of the book devoted to his upbringing in Missouri and education in New Mexico and New York City they see Predock on a Lambretta TV-175 motorbike that he picked up in Genoa while on a William Kinne Fellowship from Columbia University in 1962. There is even a sketch of the Lambretta among the many other sketches of the architectural sites he visited in Italy, France, Spain, and Greece. Predock boarded a freighter home in 1963, taking his bike with him, but soon after he bought a BMW R-695S/2 — a “big upgrade moment” in his 70-year history of riding and traveling on two wheels. Later, toward the end of the book, we see Predock bruised and in a hospital bed after he was t-boned by a car and got 17 fractures. Nevertheless, one year later, when I met him at the 2018 Vectorworks Design Summit in Phoenix, he was back on one of his motorcycles.

More than just a means of getting from point A to point B, riding a motorcycle is a way of experiencing urban and natural landscapes: panoramic, open to the elements, without the confines of car windshields or airplane windows. In turn, Predock's architecture, which he described as “examples of really looking at the underlying strata and the history of the larger geographic and cultural environment,” was nurtured by his chosen means of traversing the landscapes, in particular the landscapes of the American Southwest. This is yet another sense of how Ride is the ideal title for this magnum opus on Antoine Predock's lengthy career and spirited life.

1970s

Antoine Predock earned his architectural license in New Mexico on January 27, 1967. This we see on page 66 of Ride, at the start of a presentation of La Luz Community, a project with 100 connected townhomes west of Albuquerque. It was his first project as an independent architect, one he landed the year he got his license. He had worked for architect George Wright in Albuquerque for two years, but Predock did not appreciate Wright allowing changes that compromised a high school he designed, so when Predock met Didier Raven, who had a “pie in the sky” idea for a new community, he said “I'm in” and left a partner-track position for independence and adventure.

Sited to protect natural areas and stay out of the flood plain, the townhouses comprise a “man-made ‘escarpment-like’ landscape event,” as described in the book. The buildings feature deeply recessed glass beneath concrete fascias, massive adobe walls, and high adobe walls defining outdoor yards. Work on the project was done incrementally, “never knowing when or if the next phase was going to happen.” Practically in the middle of nowhere, “a whole second city” grew around La Luz, which wrapped up in 1974. Last year, nearly 50 years later, the project was added to the National Register of Historic Places for “taking a unique approach to incorporating its surrounding landscape.”

“A succession of projects flowed through the 1970s…”: single-family houses, such as the Boulder House in Albuquerque, as well as commercial projects like First National Bank Sandia Plaza that indicated how Predock's architectural approach could be applicable to other typologies.

1980s

Predock wrote that, after La Luz, he “needed to shed my ‘Mr. Adobe’ persona.” His first step in doing so was the “‘Corps of Engineers’ vernacular” he employed with the raw concrete, steel culvert, and bermed embankments of the Rio Grande Nature Center built in Albuquerque in 1982. It was the start of a busy decade in which Predock really honed his distinctive approach to architecture and landscape, as in the Fuller House (1984-87) in Scottsdale, Arizona, which was partially set underground for thermal stability but also featured a stepped pyramid housing the study and a tower for viewing sunsets.

In 1985, Predock departed for Rome as a fellow of the American Academy, creating a whole book's worth of sketches but also working on his practice's projects remotely. Predock wrote in Ride that the “Roman blurring of geology, landscape, and building has had a profound impact on my approach to architecture and has propelled me to seek the spirit of those layers, to delve into and even further explore the accreted deep time of every site.”

The most notable project upon his return from Rome was the Nelson Fine Arts Center at Arizona State University in Tempe, which he started in 1985 and opened in 1989. A complex program of museum, theater, and facilities for the departments of theater arts and dance led to a complex formal solution: steps and terraces, plazas and courtyards, concrete walls with stucco, all defining “an open matrix of possibilities for engagement both vertically and horizontally.”

1990s

The professional momentum spurred by Predock's “break” at the American Academy in Rome accelerated with the completion of the Nelson Fine Arts Center. As such, the 1990s appears to be his studio's busiest decade — or at least the one most full of projects synonymous with Predock — a decade that found him working in places much farther from Albuquerque than Phoenix, be it California, Texas, Wyoming, or even Minnesota and New York.

One of the most important and recognizable projects of the decade is the American Heritage Center and Art Museum at the University of Wyoming in Laramie. Started in 1986 and completed in 1993, the building makes a strong formal statement through the new cone-shaped “mountain” that is set on “a man-made mesa, a surrogate landform” with archival and curatorial spaces for the two programmatic entities housed in the building. The stretched cone has windows and deep cuts on the outside, and on the inside it is punctuated by a timber armature extending from bottom to top and housing a flue that exhausts at the cone's apex. The appealing aspects of the building led me to propose it as a valid AIA 25-year Award winner in 2018, after the jury decided not to award one.

Other notable buildings from the 1990s include: Classroom, Library, Administrative Building at California Polytechnic University in Ponoma, completed in 1992 but demolished thirty years later; the treehouse-like Turtle Creek House in Dallas, Texas, which was built in 1993 and given its own book-length monograph a few years later; the surprisingly glassy Mandell Weiss Forum / La Jolla Playhouse in San Diego (1991); and the wedge-shaped Spencer Theater for the Performing Arts in Ruidoso, New Mexico (1997).

2000s

The 2000s, also considerably busy for the studio, started with two major commissions: Austin City Hall and Public Plaza, completed in the Texas capital in 2004, and George Pearl Hall at the School of Architecture + Planning at the University of New Mexico, one of Predock's alma maters. The former building consists of a shaded entry and bleacher seating facing the public plaza on one side, angular forms clad in copper that are punctuated by a copper “tail” that projects over Austin's Second Street on another side, and a tapered atrium lobby inside that is traversed by bridges. The building is just one example of how Predock's buildings, which can appear chaotic and complex in photographs at times, are understandable and exceptional when experienced.

George Pearl Hall is a much more personal building for Predock. In 1954, at the age of 18, Predock drove an old Plymouth along Highway 66 from Missouri to Albuquerque to study engineering at the University of Mexico. Three years later, in the midst of his studies, he shifted from engineering to architecture, an act that really jumpstarted his career-long “ride.” So decades later, when he got the commission for the School of Architecture, it was “closure of closures,” he wrote in the book, not only because of his UNM connection, but because George Pearl Hall faces the old Highway 66, what is now Central Avenue in Albuquerque. The concrete facing the avenue pull apart to reveal the studios, with their glass walls and sunshades. For Predock, “the architecture school is the only building on campus where the lights are on all night,” a contention that also finds expression in a large wall parallel to the avenue that serves as a surface for movies and other projections at night.

In 2005, twenty years after his time at the American Academy in Rome, Predock embarked on his nearly two-decade-long “Silk Road and Asia Travel,” as documented in the book, around the time the studio entered and won a competition for the National Palace Museum Southern Branch in Taiwan. Although they pulled out of the project in 2008, the travel and competition hint at the global projects the studio would undertake in the ensuing decades.

2010s

International projects completed in the 2000s include the Pressdock Building at the College of Media and Communication in Qatar, a curving courtyard building with textured stone walls on the perimeter and glass walls facing the courtyard, as well as trellised walkways that harken to the Nelson Fine Arts Center; and the Gateway Arrival Building and Arts Center in Chengdu, China, pictured above. The latter is a welcome center for a new town of 100,000 inhabitants on the town's outskirts, a common typology in China. Predock designed a low-lying building with textured concrete masses colored to match the soil in the area. A tower on the edge of the adjacent lake helps the building stand out as a landmark in the town.

While the projects in China and Qatar were oceans away from Albuquerque, the most important international project that the studio designed at the same time was just across the US/Canada border, in Winnipeg, Manitoba. Predock wouldn't normally enter open competitions, but the 2004 brief for the Canadian Museum for Human Rights “was so compelling and so important to the world that we decided to enter.” Predock's studio won the two-stage competition with a spiraling design that was rooted in the earth but ascended to the sky in crystalline “cloud” floors wrapped in a curving glass facade. Likened to a cathedral when it opened in September 2014, the optimistic building features a large open interior crisscrossed by bridges lined with alabaster that glows from within (as on the book's cover) and culminates in the Tower of Hope, an element visible from afar that expresses the building's procession from darkness to light.

Another important “project” in the 2010s was Predock's gifting of his massive archive to the University of New Mexico in 2015. Two years later, the school created the Antoine Predock Center for Design and Research, housed at Predock's former studio in downtown Albuquerque and consisting of a public gallery and facilities for the School of Architecture + Planning. Just two weeks ago, the SA+P named Alex Webb the inaugural director of the Predock Center for Design and Research, which is currently being renovated and, with Webb in charge, will further develop its mission and programming.

2020s

Although the donation of Predock's archive might be considered as an act of retirement, Predock continued with work into the current decade, including single-family houses in New Mexico and Costa Rica, as well as Bahías, a group of 13 houses on Peninsula Papagayo in Guanacaste, Costa Rica. Although Predock sadly didn't live to see the completion of Bahías, the 13 houses on 13 sites are under construction and will be carried through to completion by the colleagues in his studio, particularly Paul Fehlau and Veree Simons, both of whom appear frequently in the “memoirograph.”

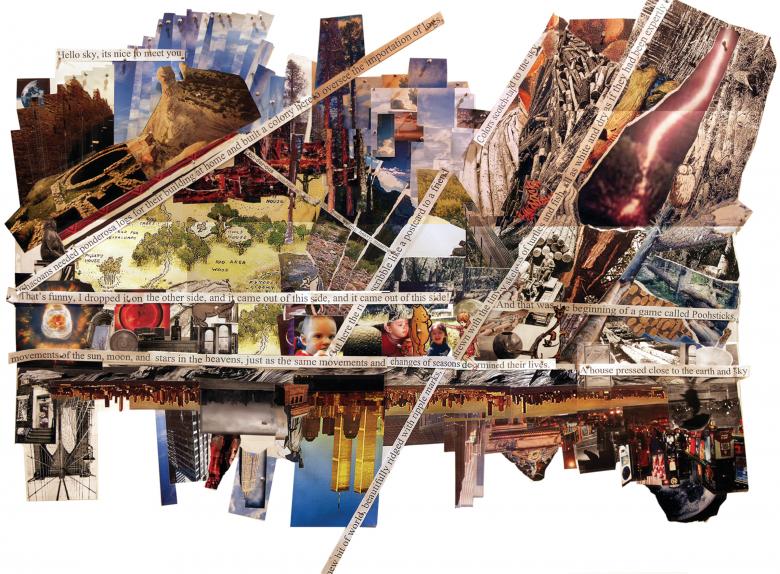

Although the contexts of Albuquerque and Papagayo are considerably different, it is hard to resist the narrative arc — an unintended one, I'm guessing — from La Luz Community to Bahías. Predock began his practice, not with a single house, but with a grouping of them on semi-arid mesa outside Albuquerque; he ended his “ride” two thousands miles to the south, with another grouping of houses, this time integrated with their jungle landscape by siting the buildings to protect trees and boulders, and through the blue-green patina of the large copper roofs. Predock's lifelong ride took him to faraway places but also enabled him — through the collages his studio created, as in the one at the top of this article — to grasp the intrinsic natural and cultural qualities of a site. He had the ability to create appropriate yet unexpected buildings rooted in their place, be it New Mexico, Costa Rica, Qatar, or anywhere else.

Ride: Antoine Predock: 65 Years of Architecture

Antoine Predock

9 x 11 inches

692 Seiten

3500 Illustrationen

Hardcover

ISBN 9780847899517

Rizzoli

Dieses Buch kaufen