The Brutalist is a sweeping tale about the immigrant experience, architecture, power, and legacy. Premiering at the Venice International Film Festival in September and released in the US in December, the film has already won a Golden Globe for Best Motion Picture – Drama and will most likely be a favorite for Best Picture once the Academy Awards nominations are announced. World-Architects watched the film recently; here are our impressions.

From The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and Metropolis in the 1920s, to Playtime and Rear Window mid-century, and Parasite and Ex Machina in recent years, the importance of architecture in shaping cinematic space is clear and pervasive. But narrative films that are centered around architecture, around the design and construction of a building, are rare. The Fountainhead (1949), a filmed version of Ayn Rand's 1943 novel of the same name, is the most obvious example. In the story, architect Howard Roark, the Frank Lloyd Wright-inspired protagonist, designs a housing project but then ultimately dynamites it rather than compromise his vision. Another novel turned into a film around the same time was Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House (1948), which saw every possible problem beset the titular character as he worked with an architect to build a new house for his family. Decades later, in Fitzcarraldo (1981), director Werner Herzog told the story of Brian Sweeney Fitzgerald's grueling, misguided attempt to build an opera house in the middle of the Peruvian jungle. Suffice to say, when architecture occupies the center of a film, it conveys the struggles, conflicts, and sometimes mental anguish of a film's main characters.

A similar approach is found in The Brutalist, the third film by American actor and director Brady Corbet. It follows Bauhaus-trained, Hungarian-Jewish architect László Toth (Adrien Brody), who, after surviving the Holocaust, emigrates to the United States to begin a new life. While awaiting the arrival of his wife, Erzsébet (Felicity Jones), who is trapped in Eastern Europe with their niece following the war, Toth settles in Pennsylvania and works with his cousin to design furniture and interiors for wealthy clients. One commission finds Toth renovating a study in the mansion of industrialist Harrison Lee Van Buren (Guy Pearce), designing and building an innovative system of shelves in a style that is more minimalist than brutalist. Van Buren is furious about his new library and Toth ends up laboring in factories, only to be brought back into the newly appreciative industrialist's fold and be commissioned to design a building in memory of his client's mother. Designing and realizing the Institute, as the building comes to be known, comprises much of The Brutalist's 3.5-hour runtime, serving as a narrative thread but also a backdrop to conflicts between architect and client, and an expression of their psychological struggles. By the end of the film, viewers come to see the Institute as embodying Toth's memories and dreams as much as Van Buren's, while the titular term can be applied equally to these two characters' creations and actions.

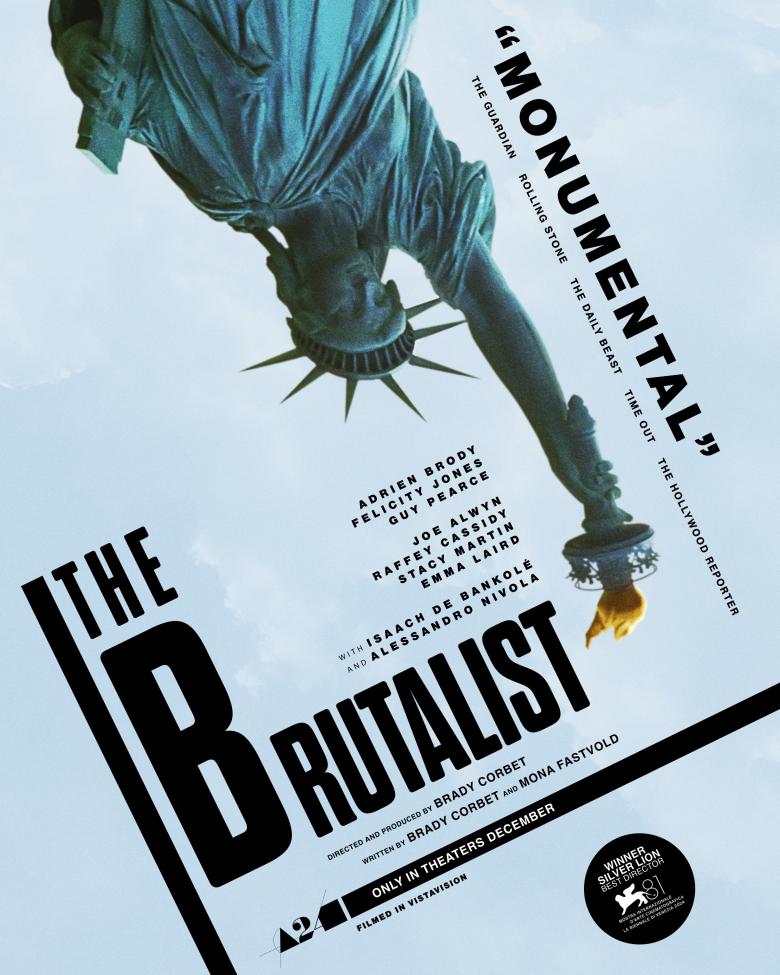

In addition to Corbet's vision, two names are important in regard to the architecture of The Brutalist. First is Jean-Louis Cohen, the late architectural historian whose name I noticed in the “Thank You To” section of the credits as they scrolled by at a Bauhaus-inspired angle (à la the poster, at bottom). Cohen, who wrote Architecture In Uniform: Designing and Building for the Second World War in addition to monographs on the likes of Le Corbusier and Frank Gehry, advised Corbet on Toth's circumstances so they did not overlap too closely with actual architects. For instance, while Marcel Breuer also emigrated from Hungary to the United States and ended up designing buildings such as the Whitney Museum of Art in a brutalist vein, he left Hungary in 1937, before the outbreak of World War II. Toth's career arc takes a similar path but is burdened by the firsthand experience of the Holocaust.

The second name is Judy Becker, who served as production designer on the film and therefore shaped the two main designs by Toth: the library in Van Buren's mansion and the Institute. For the latter, Becker researched brutalist architecture, concentration camps, and mid-century religious buildings. As first imagined by Van Buren in the film, the Institute is basically a mixed-use building, with a theater, a library, and an auditorium, but a forced marriage with the local Christian community inserts a chapel into the mix. From then on the Institute's design is focused on this religious component, with a nave-like shape and symbolic lighting; the latter is teased to viewers in the middle of the film and then shown near the end. Becker consulted with architectural designer Griffin Frazen to flesh out the minimalist spaces, but with a budget of just $10 million, the Institute — though impressive and convincing on screen — was made via a composite of models, location shots, and special effects.

Although the film's production notes describe the Institute as “a testament to Tóth’s genius, his struggles in the war, and the epic battle he engages in with the capitalist Van Buren to get it made,” it is László's wife, Erzsébet, who gives the film its moral center. Arriving in the United States a decade after her husband, Erzsébet is both critical and supportive of László's work and instrumental in the “epic battle” that plays out in the second half of the film after its 15-minute intermission. Without giving too much away, the film's denouement takes place at an exhibition, when the architect is being celebrated for his past achievements, echoing how brutalist architects that were criticized in their day were later lionized, Paul Rudolph being the most obvious example. Curiously, the designs of other Toth buildings displayed in the exhibition were generated by Frazen using Midjourney, to speed up the process and work within the film's small budget. Like the Institute itself, these designs are derivative — an issue in the realm of architectural criticism, but not in a film that is more about issues outside of architecture than the architecture on screen.