Talking Elbphilharmonie

For the day-two evening keynote at the World Architecture Festival in Berlin, architect Charles Jencks and critic Pierre de Meuron spoke about the new Elbphilharmonie Hamburg.

You might be thinking, "Don't you mean critic Charles Jencks and architect Pierre de Meuron?" Yes, those are their usual roles, but last night WAF honcho Paul Finch proposed that they reverse roles in discussing the iconic building completed last year. Apart from Jencks saying things like, "As the architect of this building...," and de Meuron saying, "As a critic I think...," the reversal was non-existent. In other words, Jencks spoke as Jencks and de Meuron spoke as one half of Herzog & de Meuron; the role-reversal did not run deep. Nevertheless, their presentations and conversation together afterwards provided plenty of insight into an important, high-profile building.

The initial slide by Jencks, who spoke first, asserted that Elbphilharmonie is the "Building of the Decade." With such a boast, surely this building would win a WAF award in the Culture category, but minus the keynote, Elbphilharmonie was otherwise missing from WAF, apparently not submitted for consideration. Jencks aligned Elbphilharmonie with James Stirling's Neue Staatsgalerie in Stuttgart, calling the former a successor to the latter in postmodern terms. Both buildings, he said, nestle into their context while standing out from it, Stirling through materiality and color and Herzog & de Meuron by piggy backing onto an older building, along the lines of their Caixa Forum in Madrid, which started the same year as Elbphilharmonie (2001) but was completed eight years earlier.

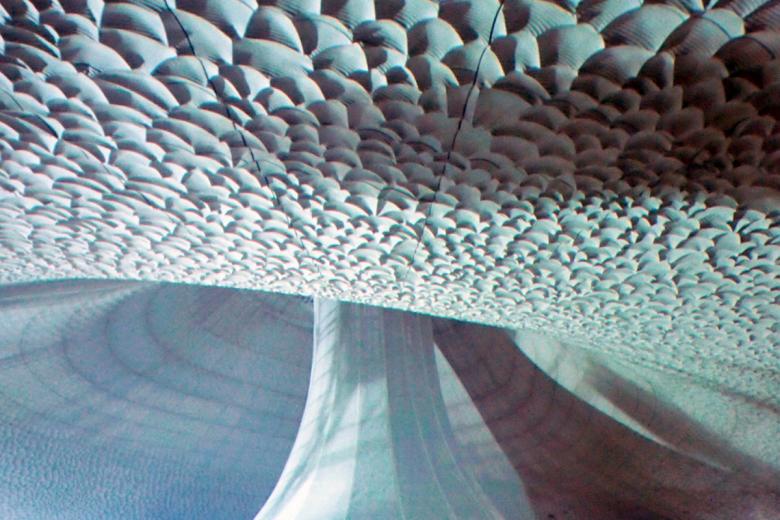

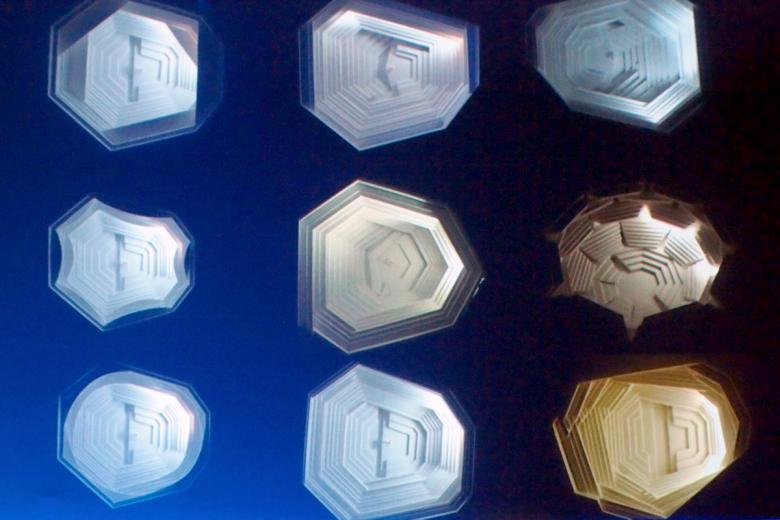

Jencks – posing as the architect but sounding like a critic – was clearly smitten with a few architectural features of the Elbphilharmonie: the glass curtain wall, whose "waves" echo the water of the Elbe that the building abuts; the long, curving escalator that draws people through the old industrial building, moving them "through the past of Hamburg"; and the numerous stairs that deliver "vineyards of people" to the concert hall, stairs he likened to Charles Garnier's famous Paris Opera from 1875. Lastly, he appreciated the design touches "inside the campfire" of the concert hall, where "fractal shapes allowed by computer" define surfaces (top image) that serve acoustical purposes but also create "an iconography people can understand."

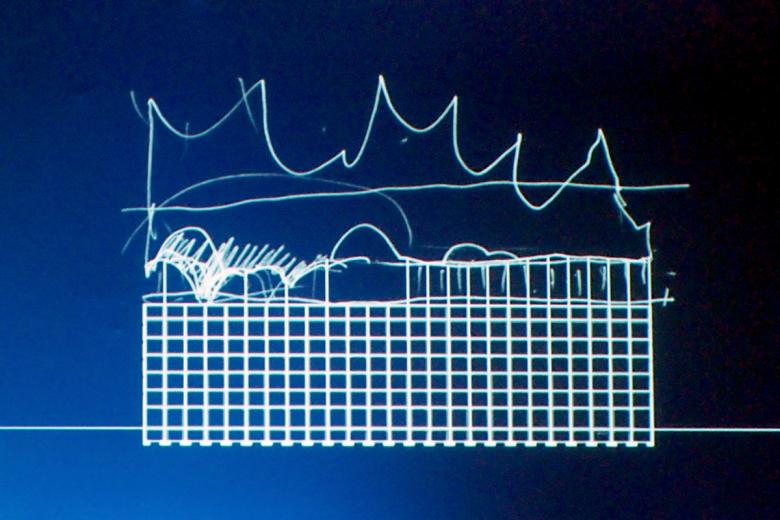

Jencks hinted at one aspect of the project's controversy: its ballooning costs. Pierre de Meuron agreed that the project is about money, but he asserted that "the majority of the money came from the city and its citizens." Furthermore, "Hamburg is a state city; they would never ask money from the [national] government." According to de Meuron, people in Hamburg are proud that the building has been completed, fifteen years after its inception and initial sketch, but so are people throughout Germany. Though ultimately it is a building supported by its citizens, a building with music at its core but also a public observation deck that gives people panoramic views over the rooftops of Hamburg.

Jencks and de Meuron's discussion of the €789 million Elbphilharmonie – a budget that Jencks asserts, alongside this year's Louvre Abu Dhabi, is the "new normal" – touched upon the project's budget but also its architecture, a design Jencks finds "so well built [and] with details so well thought through." Considering that Jencks awarded Herzog & de Meuron his eponymous RIBA prize in 2015, it's no surprise that the critic finds much so like in the "building of the decade."