Richard Serra, the artist known for monumental sculptures made with large plates of weathering steel that required people to move around them to fully experience them — making him a favorite of many architects — died at his Long Island home on Tuesday, March 26, at the age of 85.

Richard Serra was born on November 2, 1938, in San Francisco, where his father worked as a pipe fitter during the Second World War. As a teenager, Serra often worked during the summers at steel mills in the Bay Area, according to an obituary at the New York Times. In hindsight, these early years almost predetermined the steel sculptures that would become his life's work from the 1970s until his death, but Serra actually pursued painting before he moved into sculpture. Even after he abandoned 2D canvases for three-dimensional art in the 1960s, his early sculptures were assembled from unlikely materials, including stuffed animals. Before he worked in steel in situ he crafted minimalist pieces from rubber, fiberglass, and lead to be displayed in galleries.

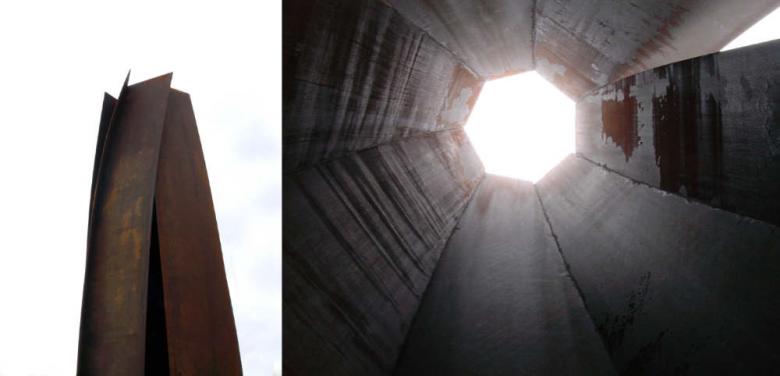

A couple of experiences at the start of the 1970s helped steer Serra to the large site-specific steel sculptures he is famous for: He spent six months in Japan with his partner Joan Jonas, studying Myoshiniji temple and gardens in Kyoto; and on the way to Japan he stopped off at Utah's Great Salt Lake to help his friend, artist Robert Smithson, complete Spiral Jetty. These experiences led Serra to understand the importance of space and movement in place-based art and pushed him to create sculptures that are not fully understood or completed until viewers move around — and in some cases inside — them. Upon their return, Serra and Jonas walked a piece of farmland in preparation for the site-specific artwork Shift, basing the placement of low concrete walls on the maximum distance by which two people could still see each other.

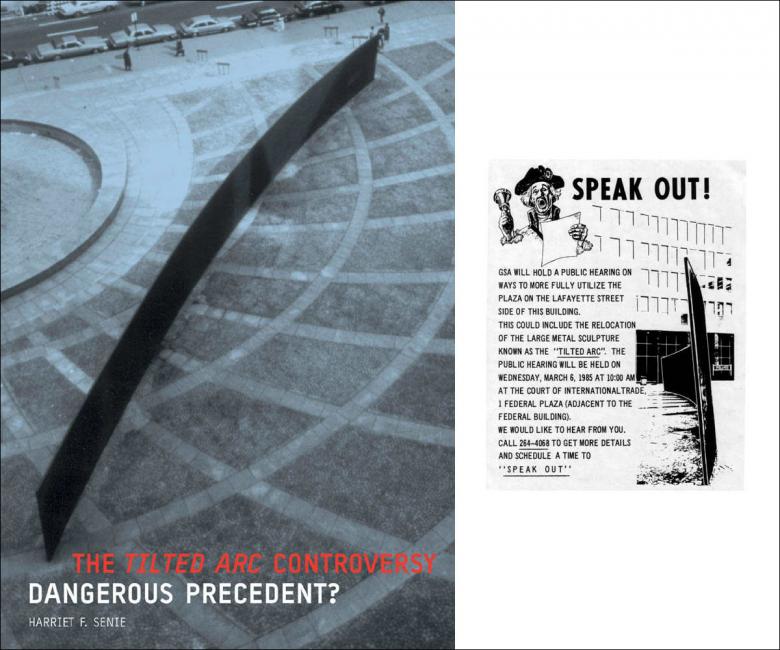

Although Shift, completed in 1972, embodied the lessons learned about movement, experience, and place, by the end of the decade Serra had realized how curved plates of hot-rolled steel could be self-supporting and tilted, lifted into place after being fabricated and trucked to the site. Early pieces in this vein were met with controversy, as when a rigger was killed by a falling plate at the Walker Center in 1975, but none was more controversial than Tilted Arc, the 12-foot high, 120-foot long, 2-inch thick rusted steel sculpture placed in a federally owned plaza in Lower Manhattan in 1981. Soon after, a judge working in the building facing the plaza started a campaign to remove the piece because he did not find it beautiful. Although Serra tried to use the legal system to save Tilted Arc, it was removed on March 15, 1989, eventually replaced by benches and mounds designed by Martha Schwartz and now occupied by a more bucolic landscape designed by Michael Van Valkenburgh.

Although the protracted legal fight over Tilted Arc was trying for Serra, the minimalist piece clearly revealed how powerful his sculptures could be — physically and mentally, not just artistically and aesthetically. Speaking from my own experiences, walking through and around Serra sculptures, especially the curved and tilted walls of steel grouped in multiples, as in the retrospective at MoMA in 2007, is nothing less than dramatic: my heart tightening when the walls lean in, a feeling of exhilaration when they open to the sky. Compression, tension, and other qualities of space that architects learn about and try to master are contained within Serra's minimal sculptures, in his nearly infinite variations of rust-covered steel.