From MoMA to West Bund

It is an extraordinary time for art museums and therefore a good moment for The Art Museum in Modern Times, which functions as a global guide through the evolution of art museums over the last century. The new book was written by Charles Saumarez Smith, a veteran of numerous art institutions in the UK. Madeline Carey, who is also a museum insider, as Head of Institutional Relations at MACBA, read the book to see what lessons it offers.

Charles Saumarez Smith began teaching the history of design at the Victoria & Albert Museum London in 1982. He has served as director of the National Portrait Gallery, director of the National Gallery, and secretary and chief executive of the Royal Academy of Arts. Such vast experience and a straightforward, pedagogical style of prose make him an excellent guide through this illustrated survey of the art museum through the past century. In it, Saumarez Smith explores two fundamental questions: How has the art museum changed over the past century? And what lies ahead for such institutions? His method is simple: a well-organized collection of brief case studies, with beautiful illustrations and delightful anecdotes about founders, collectors, and, of course, the architects.

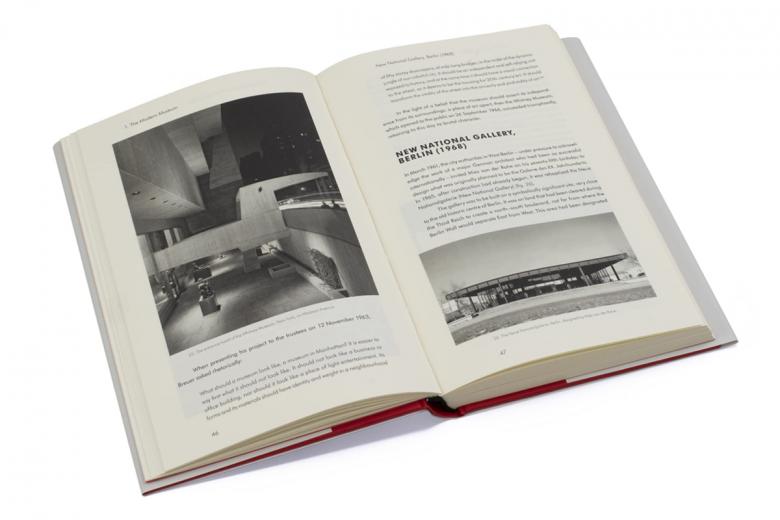

The exploration begins with the Museum of Modern Art in New York, which opened in 1939 with the radical promise to concentrate not on the past, but on the present. “It was intended to move like a torpedo into the future, gradually shedding parts of its collection to the Metropolitan Museum as it got older,” according to Saumarez Smith. In the first section, “The Modern Museum,” the author focuses on some of the best-known centers for modern art that followed MoMA, including the Guggenheim, the Whitney, and the Centre Pompidou. Perhaps most interesting for this reader were lesser-known stories of places such as the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Humlebæk, Denmark, founded by Knud W. Jensen in the late 1950s.

Located outside of the city, just one story high, and at one with the natural surroundings, Louisiana became a model for other modern museums. Jensen, a manufacturer of soft cheeses, criticized the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Copenhagen, calling it “a true horror cabinet, very much the 19th-century bourgeoisie’s exaggerated view of its own importance.” After such a scathing critique a journalist asked Jensen what he would he proposed instead and he suggested that “they ought to move into the museum’s large park, get a good architect, build a low pavilion, with not too high ceilings and good lighting, and move all the modern stuff out there.” So he did, hiring Jørgen Bo and Wilhelm Wohlert to design a relaxed setting for exhibiting modern art that has been sympathetically expanded numerous times since and remains an important reference today for private collectors and public museums.

The story of the São Paulo Museum of Art (MASP) is equally intriguing. Lina Bo Bardi, the Italian-born architect, imagined a museum that could be as popular and crowded as a movie theater or soccer stadium. She wanted MASP to be a gathering place for protest, performance art, and civic recreation: “The purpose of a Museum [sic] is to provide an atmosphere, a conduct likely to create in the visitor a mentality prepared for understanding the work of art, and in this sense no distinction is made between an old or a modern work of art.” Years after its 1968 completion, Bo Bardi, apparently quite satisfied with her project, claimed to have eliminated cultural snobbery from the museum experience. More likely that’s still a work in progress, but as Saumarez Smith makes clear, her model broke with conventions of the past and created a blueprint for ways to produce a new, more open relationship between viewers and works of art.

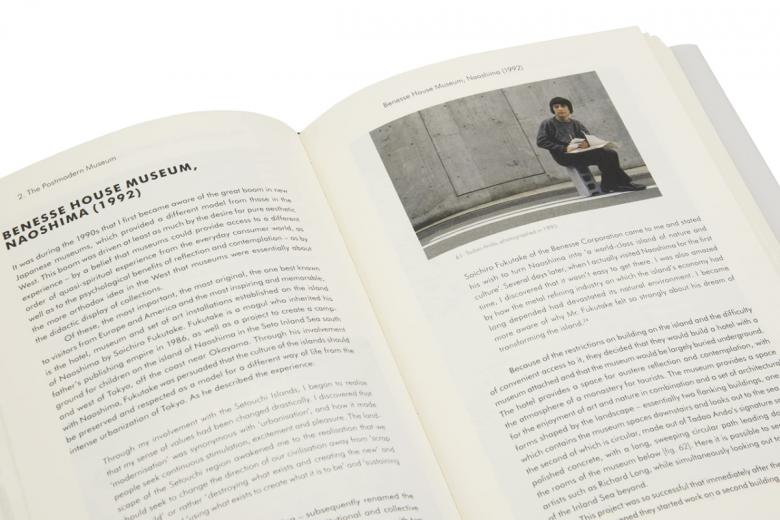

“The Postmodern Museum,” the second section of the book, focuses on museums built or redesigned in the 1980s and 90s. The last three projects discussed — the Getty Center, the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, and the Beyeler Foundation — provide a perfect summary of the final decades of the twentieth century. The Getty embodies all the contradictions of art and the art world that we’re still grappling with today. Built on a secluded hilltop above the sprawl of Los Angeles, the Getty was designed by Richard Meier, an American superstar steeped in European aesthetics. The result, Saumarez Smith explains, was glorious, but fake, a sort of Disneyland — a museum experience removed from everyday life. The Getty, which aims to serve a public role as a research library, an acropolis of learning and art, is financed by a legacy of oil money — a very American story but one that Saumarez Smith doesn’t fully interrogate.

The Guggenheim Museum Bilbao illustrates another vision: the art museum as engine for urban renewal. In this sense Frank Gehry’s project has been wildly successful and is one of the most widely discussed case studies in cultural and urban planning circles of the last several decades. As Saumarez Smith points out, the Guggenheim Bilbao represents a before and after when it comes to thinking about the role of a museum: it hasn’t been successful due to its contents or collection, but rather as a grandiose monument, attracting international visitors with its innovative architectural form and shimmery titanium skin. For sure, there are interesting things to see on the inside, but Saumarez Smith — and millions of tourists — assure us that what’s most enticing is the building from the outside, how the building functions within the surrounding post-industrial city.

Both the Guggenheim and the Getty opened in 1997, as did the Beyeler Foundation in Riehen, near Basel. Saumarez Smith points out that the Swiss project is much more discreet than the other two but just as influential. I couldn’t agree more and find this to be one of the most intriguing buildings by Renzo Piano, a go-to architect for many new museums over the last few decades. Piano places the artwork and the surrounding landscape at the center of the visitor’s experience. The architect aimed “to balance the emotion of contemplating art, which is intense and compelling, against the need for a moment of calm during the visit, a silence in which to ruminate and assimilate.” The perfect amount of natural light and an excellent collection make Piano’s experiment a clear success.

Today, in the late spring of 2021, the third section, called “Museums for the New Millennium,” feels almost like ancient history. Saumarez Smith discusses several of the greatest hits of the new millennium when cities seemed to be booming exponentially, Europe was full of hope and cultural exchange, careers shot up like rockets, and architects and museum directors became superstars. The author opens with an excellent profile of the Tate Modern, one of most influential museums of modern art in the world, and the story of Nicholas Serota, perhaps the best known and most highly-regarded museum professional in “modern times.” Saumarez is clear that Herzog & de Meuron’s Tate Modern is important as a building, a monument to Britain at the beginning of the new millennium, but he insists that it is Serota’s vision of museums in English society that shines and will prevail. Serota has clearly reinvented what a museum can be in the UK and beyond: much more than just a gallery, it is an actual meeting place, “a place that should become part of the social fabric as well of the cultural fabric.”

Another key case study of the new millennium is the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art in Kanazawa, an idyllic city on the north coast of Japan with an architecture from the Edo period. The city, longing for a more contemporary identity, created a citizens’ forum in 1996 that ended up selecting SANAA (Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa) to create a contemporary art museum. The result is extraordinary: a museum and park all in one, where the traditional authority and boundaries of a museum disappear. This project, which won a Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale in 2004, the same year it opened its doors, has been a phenomenal success and led to SANAA being chosen to design an outpost of the Louvre as well as the New Museum in New York.

Just as fascinating as the story of Serota’s holistic vision of the millennial museum, or SANAA’s poetic vision of art and nature, is David Chipperfield’s renovation of the Neues Museum in Berlin, which allows visitors to experience the space both as a historical artefact and a center for contemporary expression. This reviewer would read an entire book about Chipperfield’s renovation of the Neues, which originally opened in the 1850s. The layers upon layers of history, years of political change, and cultural transformation invite us to excavate and reimagine all at once.

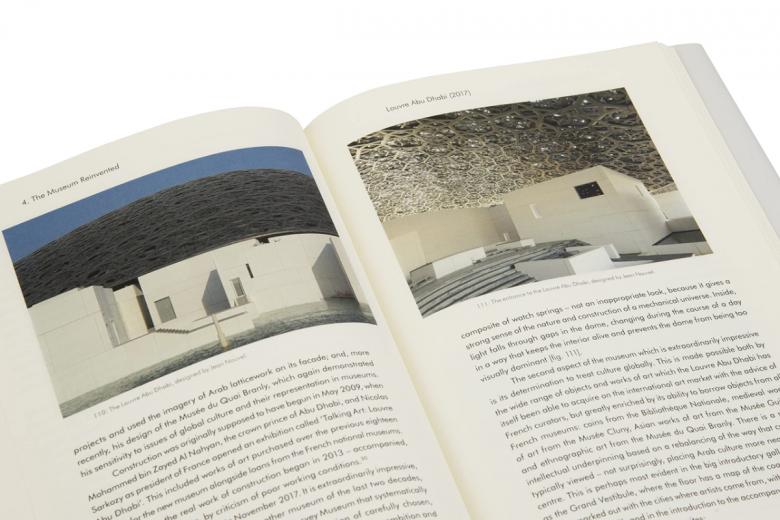

The case studies conclude with a section called “The Museum Reinvented,” in which two museums of particular interest are the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia and West Bund in Shanghai. Albert Barnes chartered the Barnes Foundation in 1922 in order to give people from all walks of life access to the visual arts. His collection was extraordinary and included works by Renoir, Cézanne, Matisse and Picasso. These European masters were hung by Barnes alongside African masks, Native American jewelry, Greek antiquities, and decorative metalworks. In 2012, in order to better serve the educational mission of the Foundation, the museum moved to a new building designed by Tod Williams and Billie Tsien. The building responds first and foremost to the needs of school groups and adult learners while simultaneously displaying Barnes’s remarkable collection in the same manner as the original.

West Bund Shanghai, which opened in 2019, houses changing displays for Paris’s Centre Pompidou. The museum is just one of many projects created by West Bund Development in order to renew an old industrial part of Shanghai in much the same way the docklands were converted into arts space in London. It’s a useful example with which to conclude the case studies because it represents some of the latest museum trends: the franchising of collections throughout the world and the growing importance of Asia as a center for new museums and contemporary arts spaces.

Saumarez Smith’s method is simple, but the book is both beautiful and extraordinarily useful — especially for museum professionals like myself. He maps out a clear path of reinvention beginning with MoMA and ending in the strange new times we live in. His examples show the ways in which museums have become more open, less rigid institutions, allowing audiences to engage with art in myriad ways, not simply following a master narrative. Saumarez Smith uses the epilogue to list key issues facing museums and summarize debates about the role of the architect and their relationship to the client; about the rise of the private museum not only in the US but in China and Japan as well; about the (im)morality of wealth and the thorny relationship between artists and collectors; and about audience expectations in an increasingly digital world. The author could certainly moderate a lively debate on many of these questions, but here he just sketches a roadmap of challenges for others to address.

Charles Saumarez Smith is not a polemist. This book doesn’t make bold statements about the problematic relationship between art and finance or museums and real estate, but the images are delightful and perfectly chosen, and the prose is fluid and bright. Many art and design enthusiasts will enjoy having The Art Museum in Modern Times on display at home or close at hand as a reference; it’s an excellent who’s who and how-to guide to the past hundred years of the museum as both monument and symbol — a looking glass for society’s evolution and constant contradictions.

The Art Museum in Modern Times

Charles Saumarez Smith

Designed by Pentagram

23.4 x 15.3 cm

272 Pages

122 Illustrations

Hardcover

ISBN 9780500022436

Thames & Hudson

Purchase this book