Interview with Lahbib El Moumni

Including Morocco's Modern Heritage in the Global History of Modern Architecture

Lahbib El Moumni and Imad Dahmani founded Mémoire des Architectes Modernes Marocains (MAMMA) in Casablanca in 2016. MAMMA is working on documenting modernist buildings that have often been forgotten and urgently need more publicity. Eduard Kögel spoke with Lahbib El Moumni during his recent visit to Casablanca.

Eduard Kögel (EK): When did you found MAMMA and why?Lahbib El Moumni (LEB): I co-founded MAMMA in 2016 in Casablanca with my classmate at the time, Imad Dahmani, who shared the same concern about the growing loss of twentieth-century architectural heritage in Morocco and the lack of awareness about its value. The name MAMMA plays with familiarity, as it sounds like the affectionate word “mama,” but it actually stands for Mémoire des Architectes Modernes Marocains [Memory of Modern Moroccan Architects]. It also serves as a tribute to the first collective of architects in Morocco, the Groupe des Architectes Modernes Marocains (GAMMA), created in the early 1950s as the Moroccan branch of CIAM.

LEB: MAMMA was born as both a research platform and a public initiative. Its main goal is to document, safeguard, and promote the architectural and urban heritage of modern Morocco, from the protectorate to the post-independence period. Beyond historical documentation, our aim is to make this heritage accessible to a wider public through exhibitions, guided tours, lectures, and educational programs. We also work closely with architects, institutions, and municipalities to foster a culture of preservation and to integrate modern heritage into contemporary urban debates.

LEB: One major challenge is the fragile condition of the archives themselves. Many architectural drawings, photographs, and administrative records are still dispersed in private offices or stored in precarious conditions in public institutions. Another difficulty lies in the absence of clear heritage policies for modern architecture. Many buildings from the 1950s to the 1980s are still considered too recent to be protected, yet they are among the most threatened. A further challenge is the limited funding available for research and conservation in Morocco, which forces us to be inventive and resourceful to sustain our projects.

LEB: The public response has been very encouraging. When we organize exhibitions or guided tours, we often see how people rediscover their own city through buildings they had never looked at closely. The administration, on the other hand, has been slower to react, although there is now growing awareness of the importance of modern heritage. In recent years, we have been invited to share our expertise with public institutions and urban agencies, which shows a gradual shift in perception. The conversation between civil society and the state is beginning to open, and that is already a positive step.

LEB: Among our most meaningful achievements is the creation of a large photographic and documentary archive on Moroccan modern architecture, which we are currently digitizing to make accessible online. We expect to launch the platform in February 2026 as the first of its kind worldwide, bringing together, in one place, biographies of architects, the locations of their projects across Morocco, and an extensive collection of drawings, notes, and photographs.

We have curated several exhibitions that connect research with the public, such as Réhabiliter le Moderne, focusing on the Ateliers Vincent Timsit designed by Jean-François Zevaco in 1952 in Casablanca, and Built from Dust, exploring modern architecture in 1960s Agadir, which was exhibited both in Agadir and in Zurich. We have also contributed to educational programs in schools of architecture and collaborated with international institutions to promote Moroccan modern heritage abroad.

What makes me most proud is that MAMMA has helped generate a new discourse about twentieth-century architecture in Morocco, one that recognizes its cultural and historical value. Today, both Moroccan and foreign architects who worked in the country benefit from a growing body of information available online and in recent publications.

LEB: Casablanca was a natural starting point because it concentrates the largest number of modern buildings in Morocco. Yet modern architecture is not limited to the big cities. By expanding our work to other regions, from Dakhla to Oujda, we aim to show that modernity took multiple forms and responded to very different local conditions. This approach also allows us to connect architects, institutions, and communities across the country and to create a national network for the documentation and protection of this heritage. It is a way of building a shared narrative that goes beyond regional or colonial boundaries.

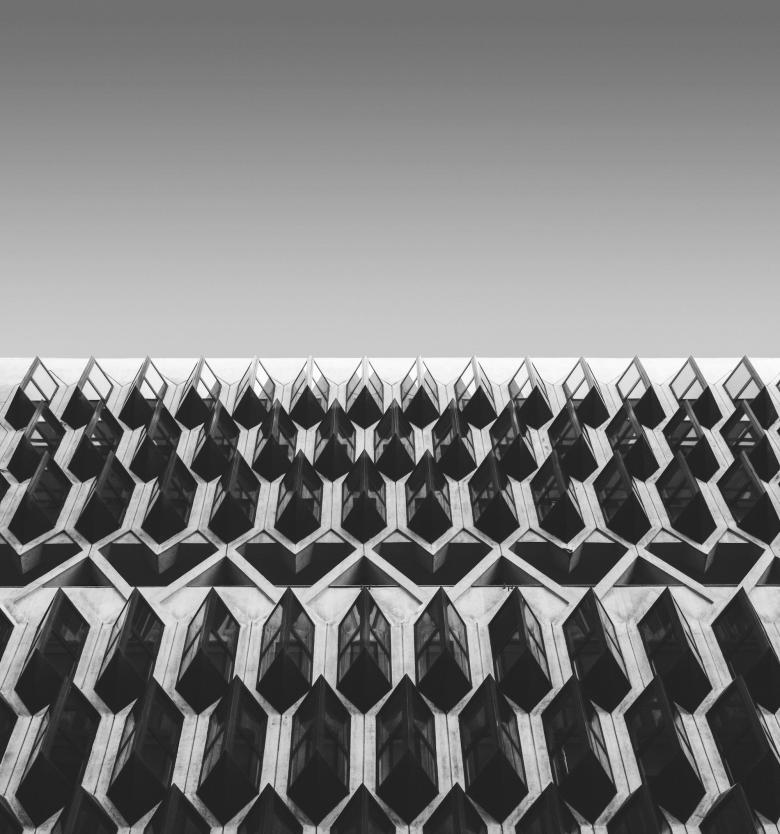

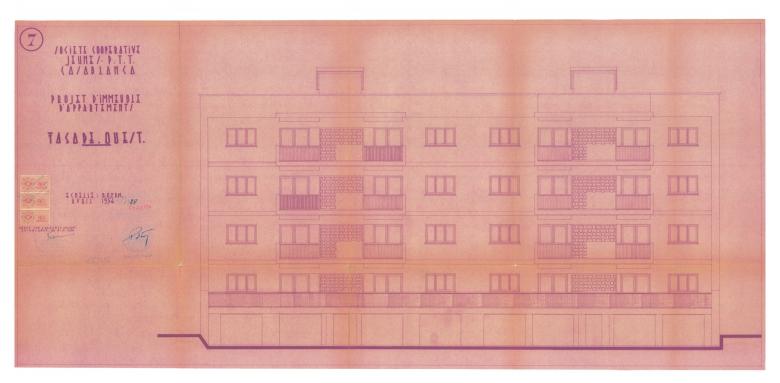

LEB: The Cité des Jeunes in C.I.L., Casablanca, is a telling example of the challenges faced by the modern architectural heritage of Morocco today. It is a housing complex designed in 1952 by the renowned architects Georges Candilis, Shadrach Woods, Robert Maddalena, Léon Aroutcheff, and Robert Jean. What was originally conceived as a new typology of housing for young Europeans ended up, after independence in 1956, accommodating Moroccan families. Given the large size of households, the dwellings were gradually adapted to local needs by residents themselves, often resulting in major transformations that were not supported by the municipality. Although residents continued to pay rent, over time the low rental rates became insufficient to maintain or restore the buildings, which worsened living conditions. However, because the complex is located near one of the most expensive districts of Casablanca, the Cité des Jeunes is now undergoing gentrification, with many ground-floor units being converted into shops that have generated a new local economy. While this can be seen as a positive development in the history of the Cité, it continues to alter its architectural fabric as transformations remain ongoing. MAMMA’s archival collection on this project highlights its original design and function, and we hope to collaborate with the municipality in the future to help better navigate the contemporary changes affecting the site. The same challenge can be seen in many modern buildings across Morocco in both private and public buildings.

LEB: My hope is that MAMMA continues to bridge the gap between research and the public, showing that the architecture of the twentieth century is part of our collective identity. In Casablanca and in Morocco more broadly, I hope to see more buildings recognized, restored, and reactivated with new uses that keep them alive. The main tool lies in our vision of building both a digital and physical network that connects archives, architects, and institutions across the country, so that modern heritage becomes an integral part of how we think about the city today. In the end, our goal is not nostalgia but continuity, ensuring that the memory of modern architecture inspires the future of urban design in Morocco.

On the research level, our ambition is to rebalance global interest in modern architecture. Much of the existing attention still focuses on the Western sphere, while our region and the “Global South” more broadly represent a unique context where many of the ideas that shaped modern architecture first emerged and transformed, yet remain under-recognized. By sharing MAMMA’s research on Moroccan modern heritage, we aim to position our country, and Africa more generally, as a vital source of knowledge and inspiration in the global history of modern architecture.