Paid Content

Handling the heat

Johanna Deinet and her K&L Architekten team, Saikal Zhunushova and Andy Senn all design buildings that get by without complex air conditioning technology. Even on hot summer days, constructive solar shading elements such as shutters and blinds keep their low-tech buildings cool.

That heating needs must be reduced in particular to help protect the environment is a view widely held within the building sector. But with heatwaves on the rise and average temperatures climbing, does this still hold true?

Andy Senn: In Switzerland we’re used to a temperate climate with few really hot days. So thermal insulation has traditionally been the focus of our building regulations. But with the rise of global warming, protecting buildings from excessive heat has suddenly become a major issue, too. That poses us new challenges: when the outside temperatures are high, it’s far from easy to keep a building cool. It takes sophisticated solar shading; it takes the smart use of cooling processes; and it takes the right choice of construction materials. The building’s use must be carefully considered, too: a classroom of 30 schoolchildren will heat up much more rapidly than an office.

Saikal Zhunushova: Not that we should neglect the insulation dimension. I learned that in Kyrgyzstan, where I grew up, and where I still work today. It’s very hot there from spring to autumn. So many Kyrgyz use just a five-centimeter-thin layer of mineral wool to insulate their brick-built homes. That’s not enough, though. The best way to cope with a climate of major temperature variations is with a soft insulant that protects from the cold in winter and onto which you can fix thicker materials such as fiberboard panels to keep out the summer heat.

Insulation is particularly important if you’re looking to utilize passive heating sources such as incoming sunlight or the body heat of the building’s occupants. If you don’t have adequate insulation, the benefits of these will be lost. And there’s a further side to insulation that is often underestimated: it’s crucial to comfort, too, because it prevents your interior walls from feeling unpleasantly cold in winter and too hot in summer.

Johanna Deinet: Heat is a particular building challenge with wooden structures. Wood is a poor storer of thermal energy. To keep a wooden building cool without resorting to air conditioning, you have to ensure that you have sufficient storage mass. For a night cooling system to work, for instance, you need to have the right fills and wall constructions. It can be particularly advantageous here to combine wood with other natural building materials – by adding clay panels to the inside walls, for instance, and then coating these with clay plaster. This will also help provide and maintain a healthy indoor climate.

You largely use construction techniques to protect your buildings from the heat, and you make scant use if any of complex building technologies.

Andy Senn: Staying low-tech is an autonomy issue. Do you have your architectural solution with solar shading elements readily at hand, or are you going to be reliant on Air Conditioning & Co. instead?

There must be a lot of bad architects out there, then: the market is full of high-tech air conditioning and ventilation systems.

Andy Senn: There’s a lot of interest in low-tech architecture, too, among builders and (in particular) in the academic world. What’s still lacking, though, is a willingness to make it happen. Sure, without all the technological controls, you’ll have more variations in your indoor temperatures. So you may need to wear a pullover indoors in winter and shorts in summer. At the same time, though, your subjective sense of comfort will always be higher in low-tech premises. After all, many people dislike the sheer feeling of being at the mercy of technology.

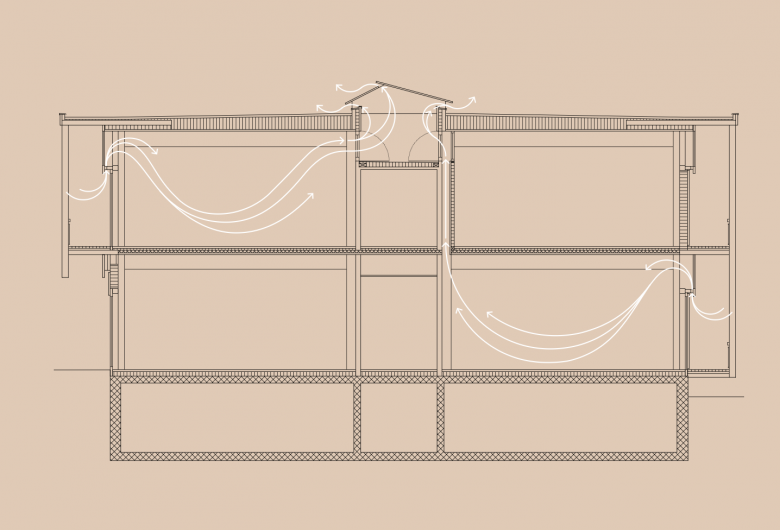

Public-sector building projects face a particular dilemma here. How much risk can they reasonably run? Are they willing to defy certain norms and conclude a user agreement? Our Center for Agriculture in Salez is all thanks to St.Gallen’s former cantonal building director Werner Binotto. If it hadn’t been for him, the facility would never have been built the way it was. The Center’s principal Markus Hobi played a crucial part, too: as a key future user of the facility, he was a keen and committed supporter of the project right from the start. What we designed for the Center was a wooden construction with no building automation, no ventilation system and no air conditioning system. Instead we designed special ducts to provide the building with cross-ventilation, based on the natural ventilation techniques that were traditionally used in stables. We planned balconies to give shade; and we incorporated sliding shutters that could be positioned by the occupants themselves to provide solar shading on hotter days.

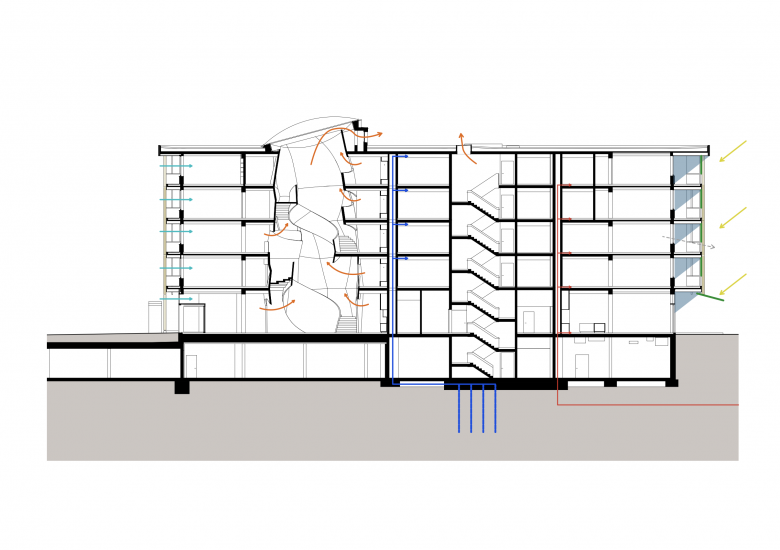

Johanna Deinet: We had the privilege of developing a project for Blumer Lehmann AG, a timber construction company that is very eco-minded and is more than willing to push the boundaries, too. For their new head-office building in Erlenhof near Gossau (St.Gallen), they were keen to utilize every possible benefit of modern wood construction. So, drawing inspiration from Andy’s Center for Agriculture, we also designed our new building’s facade with wraparound balconies to give shade, and incorporated a night cooling system featuring automated ventilation flaps. Additional cooling is provided by activated piles that extract cold from the ground and feed it into the various offices.

The key to the success of any low-tech construction is to adopt and maintain a holistic planning approach: climate-minded construction should never be viewed separately from broader spatial organization and overall layout design. The night cooling in the new Blumer Lehmann building, for instance, only works because all the company’s personnel work together in large open-plan offices. If the building were full of smaller individual offices, the cool air would not be able to circulate enough.

Saikal Zhunushova: I get annoyed when low-tech is depicted as intentionally ‘going without’. Nobody wants to go without. I prefer to tell people about all the things they gain – like lower running costs. A Kyrgyz family will tend to spend the equivalent of some USD 300 a month on gas for heating and cooking. In my houses, which use passive heating, they’ll be paying around USD 50 instead. And there are emotional benefits, too. The fact that I use wood and straw in my constructions, along with clay plaster, really touches some people: it reminds them of their grandparents’ homes, and brings back many fond memories.

I appreciate, of course, that some construction projects—like a new hospital, for instance—will need to include sophisticated building technology. The air in Kyrgyzstan is dirtier than it is in Switzerland, and you’ll often have dense smog hanging over a city. So the desire for ventilation systems with filters is an understandable one. But here, too, I always advocate incorporating only the minimum required. However, I always advocate only installing the bare essentials and would like to see a healthy skepticism towards technical solutions, as exemplified by Bavarian architecture professor Florian Nagler.

Your buildings are often flagship projects, sometimes new constructions have to be developed and components used in unconventional ways. Given such needs, what do you look for most in your suppliers?

Johanna Deinet: With the Blumer Lehmann building, the solar shading roller blinds were a particular challenge. We wanted to mount these right out on the facade, to ensure good air circulation and create a kind of ‘climate buffer zone’. By placing the blinds away from the windows, we could also keep the parapets clear, so that even when the blinds are closed, you still have the landscape views.

At the same time, we wanted these blinds to be aesthetically appealing and slightly transparent. So the product we opted for was the filigree cable-guided textile blinds manufactured by Griesser which are automatically deployed if the sun starts to shine. These blinds should not really be used in such elevated and exposed positions on a building’s facade, where they could be damaged by the wind. But this is a risk that we elected to take, in consultation with the builder. And if we do get the occasional hot day with strong winds, too, some of the blinds will be retracted and the building will just get a little warmer.

Saikal Zhunushova: In Kyrgyzstan we don’t have any external solar shading in the form of shutters or blinds. I would love to build a big apartment house there with wooden window shutters. They’re not just a simple and efficient way of providing protection from the sun: they’re a great design element, too.

In Kyrgyzstan we also have the additional challenge of getting the right materials for our balcony constructions. If we use the building materials that are widely available, such as concrete, the large mass that this creates in front of the windows will continually heat the interior from outside. This can be mitigated, though, by filling the balcony with plants so that less heat accumulates, or by using a lighter material such as wood for the balconies’ construction.

Many manufacturers today are very keen to emphasize their eco-credentials. With some, this may be little more than a marketing ploy; but others seem genuinely committed to environmental issues and concerns. Is a company’s attitude a criterion for you when you come to select your suppliers?

Andy Senn: With public-sector buildings the procurement process is very tightly prescribed, and we have minimal scope in selecting our suppliers. If we can, though, we’ll always try to work with local manufacturers, planners and craftspeople. Eastern Switzerland has some excellent window manufacturers and timber construction specialists, for instance, who are devoted to their trade and have the highest product standards. With partners like these you’re on the same wavelength immediately, and they’re a true joy to work with.

Johanna Deinet: With collaborations like those, everyone can learn together. Smaller firms with strong local or regional roots are often more open to new developments, too. So it can actually be easier with them to improve a product or even design new ones.

Saikal Zhunushova: The companies I’m drawn to most are the ones that make money available for apprenticeships and research, offer architectural awards or support educational projects. Our universities urgently need third-party funds to conduct their research and promote innovation. Awards and publicity can shine an invaluable spotlight on the best of the projects here. And this in turn can influence builders and developers in their own future decisions.