A Masterpiece of Modern Housing 70 Years Later

Halen in the Fog

All photographs by John Hill/World-Architects

If life gives you lemons, the saying goes, you make lemonade. And if Switzerland serves up some fog on a Saturday morning, you make the most of it, visiting a building whose overgrown concrete surfaces just look better bathed in gray. Look at some photos from a recent visit to Siedlung Halen, the masterpiece of Swiss architecture designed by Atelier 5 seven decades ago.

December 1, 2025, will mark exactly 70 years since Atelier 5 submitted a building application for Siedlung Halen, a housing settlement with roughly 80 residential units in a forest clearing near Herrenschwanden, just north of Bern. It was the first project by Atelier 5, the Bern architecture studio founded by five young architects (Erwin Fritz, Samuel Gerber, Rolf Hesterberg, Hans Hostettler, Alfredo Pini) in May 1955. Inspired by the housing of Le Corbusier, Atelier 5 proposed a high-density, low-rise development with rows of narrow units (between 3.8m and 4.81m wide) terracing down the sloping site. Construction began in early 1959 and concluded in late 1961, with all of the units sold by the end of 1963. Even before it was fully sold, the project was receiving international attention through coverage in architecture magazines. The project's sustained importance can be found in the Bern Canton naming the Halen Estate a protected building in 2003.

Atelier 5 continues to practice to this day—remarkably in the same building, the former Ryff factory at Sandrainstrasse 3, that the founding members moved into in 1956. Like many architects and other creative types whose first works are often the most innovative, Halen remains Atelier 5's most famous work. Hence, when this New York-based writer was in Zurich recently for the annual meeting and holiday dinner of PSA Publishers, the company behind World-Architects, I ventured to Bern on a free Saturday, determined to get a peek at Halen. Thankfully, the housing estate is welcoming of visitors, provides guided tours, and sells a 2010 book devoted to the project in its shop. Although I did not go on a tour, I did walk around the estate and take some photos—and later saw a few other housing projects, by Atelier 5 and others, before taking the train back to Zurich that evening. Click below to look at a slideshow of photos, with captions, from a foggy morning visit to Halen.

While Halen's remoteness makes getting to it by car the most logical choice, it can be reached via the 102 bus from Bern's main station. Steps from the Thalmatt bus stop next to Halen are two later Atelier 5 housing projects: Thalmatt 1 (1974) and Thalmatt 2 (1985), the latter pictured here.

Whereas Halen's roughly 80 units are comprised of just three types, the complex stacking of the 37 units at Thalmatt 2 is made up of a whopping 30 different types.

Near Thalmatt 1 and 2, on the street named Thalmatt, is a row of housing terracing up from garages at street level.

Although this housing resembles Atelier 5's work, it is not of their hand. Who designed it remains a mystery—both to me and others.

Multiple paths lead from Thalmatt through the trees to Halen.

The main path leads to Halen's driveway and its structured parking; note the gas pump at left, added in 1981.

But the path I followed delivered me to the community pool at the topmost level of Halen.

An important consideration in Atelier 5's design was maintaining privacy within a dense development. As Inge Beckel wrote in a 2011 visit: “A solid wall marks the transition from the public to the private sphere; after passing this wall, one enters a vestibule, through which one reaches the actual house.”

A single tall chimney serves as a landmark within the estate, here seen across a walkway between studios, on the left, and the back of the shop and restaurant, on the right.

The chimney is from the estate-wide boiler plant, which can be seen here, at left, looking down another pedestrian walkway cutting across the site.

The chimney also roughly marks the location of the central plaza, which is fronted by the shop and restaurant.

The shop and restaurant lend the rural development a bit of an urban feel.

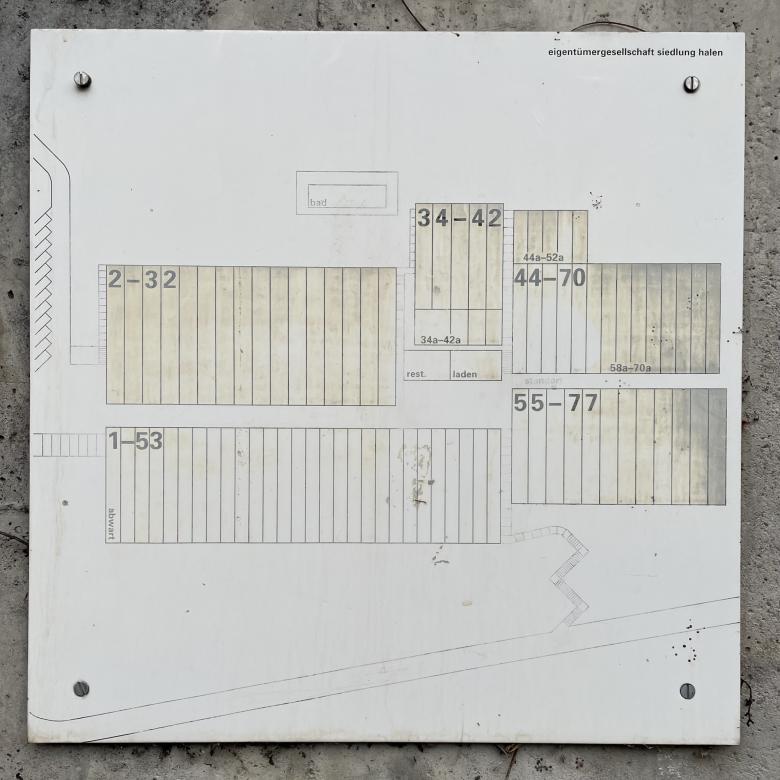

This map mounted to the boiler building shows the layout of the estate and hints at the distribution of unit types: 1–53 and 44–70 are type 380 (3-story with 5 bedrooms); 2–32, 34–42, and 55–77 are type 12 (also 3-story with 5 bedrooms, but wider than 380); "a" designates studios.

The plaza, quiet this foggy morning, is softened by a grid of trees.

This sculpture by Bernhard Luginbühl, visible next to the stair in the previous photo, was buried at the edge of the estate in 1961 because nobody wanted to buy it, but then it was unearthed in 2002 and moved to the plaza.

Like the entrances to the units seen previously, those facing the plaza have solid walls for privacy and canopies for shade and shelter.

Walking down the hill from the plaza, the lowest units end at trees and grass rather than concrete paths.

Continuing farther down the hill, a stair branches off to lead down to the roadway below the estate.

On the Sunny Side of Bern

The morning fog broke, leading to a pleasantly sunny autumn afternoon. Taking the 19 bus, I ended up at Siedlung Brunnadern, four apartment buildings designed by Atelier 5 in 1970 for a site in the diplomatic quarter.

Unlike the density and site coverage found at Halen and Thalmatt 1 and 2, the predominance of villas around Brunnadern led the architects to design what are effectively four towers in a park-like setting.

The architectural signature of the project are the spiral stairs housed in concrete cylinders and capped by spiraling metal roofs.

Privacy at Brunnadern came via signs of “Private Property. No Trespassing”—the antithesis of Halen—that kept people like me at the perimeter of the site, beyond the trees.

A colleague tipped me to a more recent cooperative housing project in another part of Bern: Huebergass, designed by GWJ in 2021.

The project consists of 103 affordable units in five four-story buildings.

The five buildings define a central alleyway that the architects describe as the “vibrant central axis of the settlement, connecting all communal and private spaces,” and where “wooden extensions facing the alleyway serve as both stairways and private balconies.”

Unlike Halen, whose plaza and streets were predominantly empty, Huebergass was full of life, with kids playing in the alleyway and others yelling down from the balconies. It was a clear expression of how architectural views toward community have changed in the last 70 years.