Stone Monoliths of History

WXCA, a young architecture studio from Warsaw, designed both the Polish History Museum and the adjacent Polish Army Museum. Ulf Meyer recently visited the two institutions that had their grand openings last year, sending us his impressions.

The Warsaw Citadel, off-limits to the public since its inception in the 1830s, has been transformed into a vast museum campus featuring two impressive new buildings: The Polish Army Museum and the Polish History Museum. Both buildings were designed by WXCA, the local architectural office that was founded in 2007 and now numbers more than 75 architects. This project, one of the largest museum complexes in Europe, was their first major commission — an unusual and impressive start for the studio. Marta Sękulska-Wrońska, the CEO of WXCA, and Szczepan Wroński were recent graduates of the Warsaw University of Technology when they won the competition, in 2009, to design the Polish Army Museum, with the commission for the Polish History Museum following in 2016.

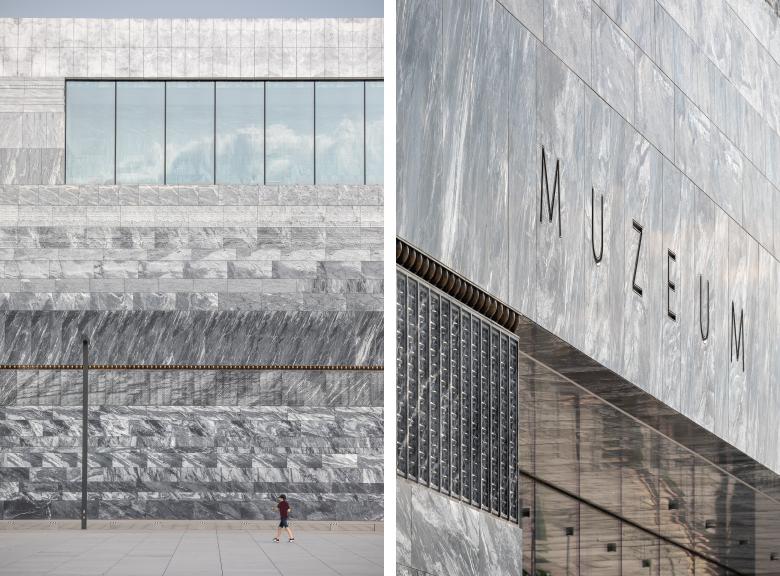

The Polish History Museum stands at the heart of this new cultural complex in Poland’s capital city. Its scale and form evoke the bulk of a massive box — a "Walmart on steroids," though one clad in grey and black Portuguese marble. The marble slabs are arranged in horizontal strips, revealing the layered structure of the stone. Sękulska-Wrońska explains that this layering "adds diversity through variations in tone and texture." Cut into the walls of the monolithic facades are reliefs that “draw inspiration from architectural traditions of Poland,” according to the architect, though this symbolism may not always be immediately clear to visitors. The striking treatment of the beautiful stone as a shallow veneer or tapestry reflects a bold, anti-tectonic approach, characteristic of contemporary CAD-driven designs of young architects.

Both buildings are simple, orthogonal volumes; their power stems from their basic shapes, while their refinement comes from distinctive design elements on the facades but also the generous spaces. The interiors of the Polish History Museum are reminiscent of Peter Zumthor’s Thermal Baths in Vals, but on a vastly different scale and more as a shallow image — for example, in how the stone veneer hides giant steel trusses that span the big box. The architects visited Ludwig Mies van der Rohe`s Barcelona Pavilion on a trip when they were students and were deeply impressed. Like Mies, they use the patterns of the stone (and wood) as decor for otherwise purely abstract and orthogonal architecture on a gargantuan scale.

The Polish History Museum was founded in 2006 but originally had no permanent home. An international architectural design competition was held for the museum, to be built on the Trasa Łazienkowska highway. The winner of that competition, Paczowski et Fritsch of Luxembourg, saw their design scrapped and later the decision was made to relocate the museum to the Citadel grounds. This time, WXCA was commissioned for the relocated museum, with a plan that called for three buildings arranged around a central plaza: two buildings for the Polish Army Museum flanking the taller Polish History Museum in the middle. Symbolically then, the military flanks national history.

The citadel on a plateau, north of the city center was constructed by the Russian Empire's military forces and overlooks the Vistula River, separated from the city by an embankment. The rectangular museum volumes echo the shape of the barracks built by Tsar Nicholas I. Unfortunately, a planned pedestrian bridge that would connect the citadel to the neighboring residential neighborhoods has not been built yet. Thus, the citadel remains a city within the city for the time being.

The box for the Polish History Museum measures 190 meters in length and 64 meters in width, reminiscent of a “block of marble, only lightly carved,” according to Grodzicki. The 27,000 square meters of stone surfaces inside and out have been processed in six different ways, varying in shades, surfaces, and textures; the horizontal bands evoke layers of archaeological excavation, but the abstract, graphic shapes and patterns of the carvings can only be seen from an angle. The vast new museum offers 44,000 square meters of usable floor space, including a library, restaurant, conference rooms, a large auditorium, a cinema, and a roof terrace offering sweeping views of the Warsaw skyline. But it is still largely empty, with the permanent exhibition set to be unveiled in 2026.

Of its two planned neighbors, only one has been completed: The Polish Army Museum, a department of the Polish Armed Forces, occupies a striking first new building to the south of the Gwardii Pieszej Koronnej Square. The museum consists of eight exhibition halls under one large roof. Its facade is made of cast-in-place concrete, rising up to 7.5 meters, with a red color that references the brick architecture of the fortress. The shape of the building is a simple rectangle, and its facade is divided into large panels, with a bold cornice. While the gable beam is smooth, the relief on the walls evokes chevrons, the insignia denoting a soldier’s rank on the upper sleeve. This chevron pattern continues through the interior, where all technical infrastructure is discretely integrated into the walls and ceilings. Encompassing 12,000 square meters of space, the museum’s red profiled concrete facades conceal the a ground exchange system for heating and cooling; the system involves 91 vertical boreholes drilled 150 meters deep into the ground. Interestingly, the museum does not feature a bookshop, as Polish military facilities are prohibited from selling goods to the public.

Despite its giant size, bold design, and all-too-prominent location, the Army Museum will be complemented by a twin building opposite the plaza — should the budget be available and the political will be strong. Once completed, the two museums will frame the guard square, with the central History Museum flanked by the two lower volumes of the Army Museum. It will be a truly grand ensemble for a nation that has seen its independence destroyed several times across its history, and is thus longing for such an anchor.

Poland’s accession to the European Union in 2004 provided the funding. Between 2004 and 2013, 5.5 billion euros were allocated as co-financing for over a hundred new cultural buildings in Poland, making it the largest recipient of EU financial support for cultural projects. This funding catalyzed a construction boom, and cultural institutions also became symbols for political campaigns. The ultra-conservative Law and Justice Party (PiS) recognized the power of museums as tools in their "culture war" over Polish history. The party remained in power for eight years, using the construction of museums as one of their political tools. Despite the exhibitions being unfinished, the museums were hurriedly opened before the 2023 elections as a grand political gesture. Now, a new regime and a more moderate society can fill the big boxes that their predecessors left behind.