The return of 'The Notebooks and Drawings of Louis I. Kahn' after nearly 60 years

Lou, Then and Now

The Notebooks and Drawings of Louis I. Kahn, released in 1962, is considered the first monograph on the great American architect. It is also the first of nearly 100 books by influential "information architect" Richard Saul Wurman. Long out of print and hard to find, a facsimile edition — now raising funds via Kickstarter — is being prepared by Designers & Books. This occasion prompted World-Architects to reach out Wurman to learn more about his relationship with Lou (as his friends called him), Notebooks, and why the book is relevant today.

Somebody’s doing my biography now. In telling stories about my life to him, my biographer has become a Louis Kahn addict. He realizes so much of my life — even though it’s veered off seemingly in such a different direction — is so based on Lou. Lou has been in my life — then and now — he molded my life, and he gave me permission to do things outside of architecture.

I wanted to be a painter. My father, who was in the cigar business, said to me, “You can be a painter if you want, you can go to art school.” A friend of my father got his degree in testing, like those preference tests you’d take in high school to figure out what career to go into. So I took one of his tests and the analysis listed three things: archaeology, architecture, and hairdressing. I discounted hairdressing, but I thought that if I went into archaeology I couldn’t move into architecture; or if I went into painting I couldn’t switch to architecture. But if I went into architecture, I could move into those other subjects. And that’s exactly what happened!

I applied to one place, University of Pennsylvania, and got accepted. I didn’t know anything about Penn but someone in my high school said it was the best school in the country. It turned out to be the best architecture school in the country for about five or six years in the 1950s. There was Kahn and Robert Geddes and Robert Venturi and Mitchell Giurgola and Steen Eiler Rasmussen … on and on, everyone was there. Lou was a magnet. After one semester I wanted to quit. It was too easy and I didn’t think the other students were very smart. My father said, “Why don’t you stay until the end of the year?” So I did, and it got much more interesting. I was first in my class; my watercolors won in a university-wide art contest; I got the medal for first-year design. My ego was fed and it seemed that maybe somebody wanted me there.

Then in my second year [in 1953] I went to go see this guy talk — this ugly, funny, scarred little guy talking with a high voice. He wasn’t lecturing about architecture so much as he was talking about truth. I was enchanted by it — it was astonishing! I went home and told my parents, “I met someone who’s going to be famous.” Lou was the first person that I’d ever listened to who spoke the truth; he didn’t tell any lies. There was a flow of genuineness that I’d never experienced before. Not that I had a bad upbringing or anything — it just wasn’t normal! He was a palpable conscience and was different than anybody I’d ever met.

As the years went on, I had Lou for an undergraduate studio and I had him for my graduate thesis. I was going to become an architect with a capital A and work for Lou; that was the plan. I got my master’s degree [in 1959], but he didn’t have any work so I worked for another architect for six months. And then he called me — on Christmas Day! — and hired me and my friend David to work on two odd projects: the World’s Fair in New York and a barge that goes up the Thames and gives concerts. “Come in nights and weekends,” he said, “and the three of us will work.” I started working there on a Friday and on Sunday he sent me to London. I’m 22! Lou gave me blueprints of his charcoal sketches, but the people in London were expecting working drawings to build the barge from. It was a crisis, and I had to decide if I went home or stayed and figured out how to do it. That was one of at least four situations that Lou put me in that molded me as a survivor and changed my career, changed my life.

After that Lou became insinuated in my life: We used to go to baseball and football games together; he used to come to my parents’ house for Thanksgiving; he came to my apartment with my first wife. So I wanted a piece of Lou, the things he said, the things he did. I wanted something that I could open up to see his process. I wanted the drawings that were the beginnings of things. So I went to him and said, “Lou, I’ve never done a book but I would like to make one with your sketches.” I didn’t expect him to say yes, but he did, and then he started to select the drawings. I stopped him and said, “No, no. I want to choose the drawings. I want this to be the book that I want to have.” He agreed and said he’d be interested to see what I selected. I think he realized he could learn from it.

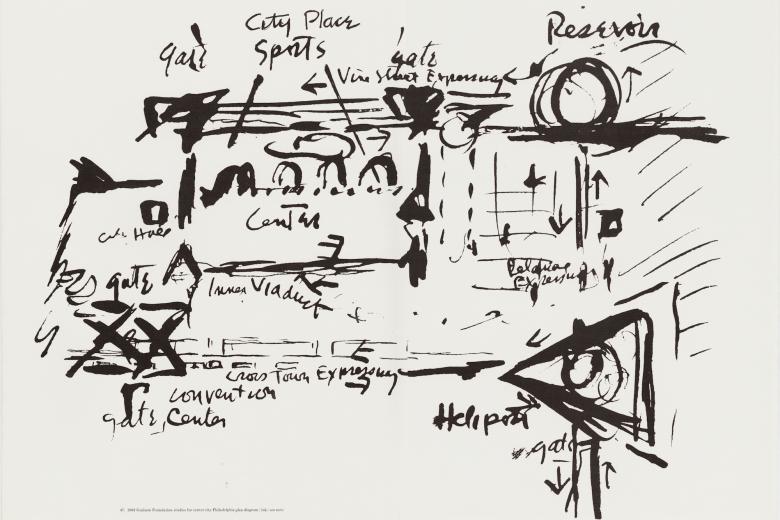

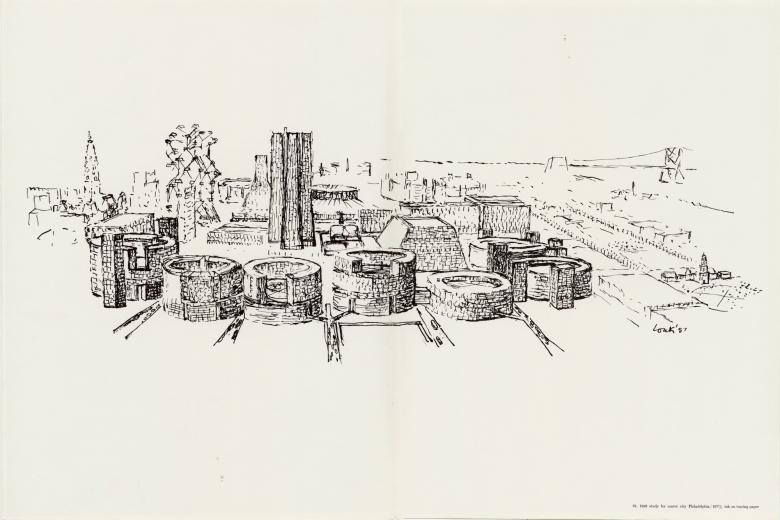

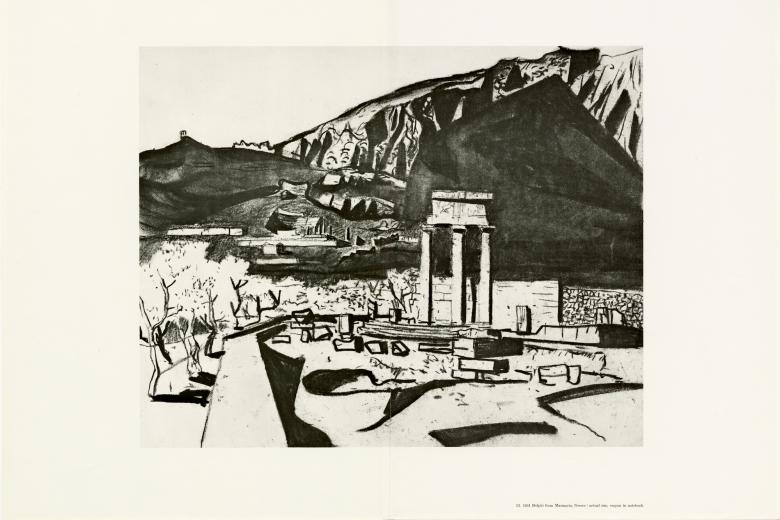

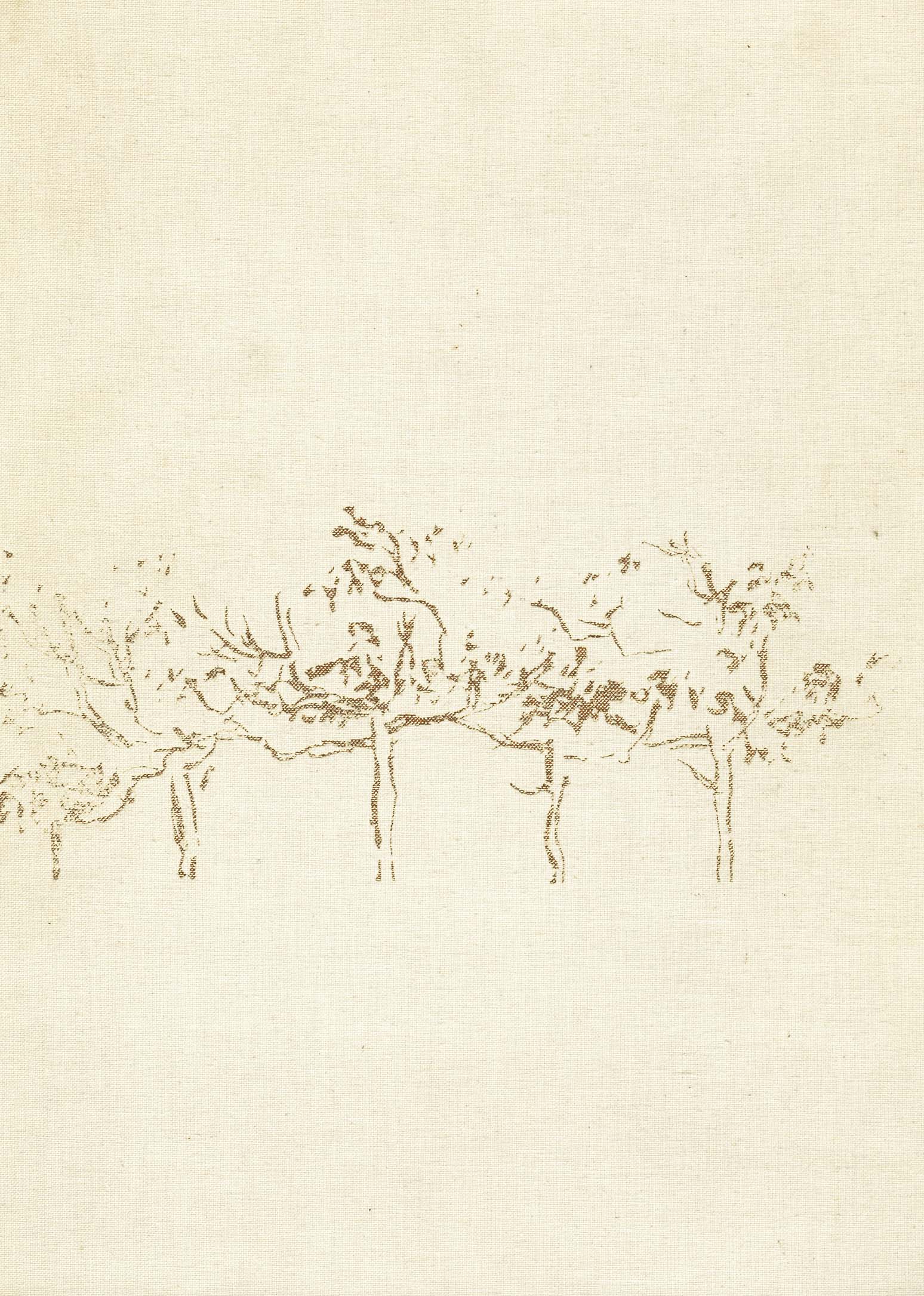

There were early drawings with circles — of Mikveh Israel and the meeting house at the Salk Institute [both unbuilt]. There were trees that I put on the cover from a drawing of the garden at Yale. I saw those trees, pulled them out and put them on the cover in gold; I knew how much he loved gold leaf. There were drawings from a library competition in St. Louis. It was about seeing the drawings before the final drawings. There’s only one final drawing in the book: of the Richards Medical Building at Penn. Notebooks was about process; it was trying to understand his thinking, the conversation he had with the page — of making a mistake and reacting to it, smudging it out. He liked vine charcoal and his buildings are unique because that’s the way he drew. These are corny words, but I wanted to get in the flow of Lou’s mind so that I could serve the "angels of clarity." There were many, many books about him, but he loved that book. He understood what it was and I think he found his essence in that book.

Architecture goes through cycles of architects being in and out. I’ve lived through nobody knowing who Lou was, when the students knew him — worshipped him — but no one else did. He died [on March 17, 1974] and I think Paul Goldberger’s obituary of Lou was on the front page of the New York Times. Then they found out that his office was bankrupt and that he owed $500,000 (the equivalent of like $5 million now), so people thought everything would get auctioned off or destroyed. In a unique event, someone got to the governor of Pennsylvania and then the state senate approved a one-time-only purchase of all Lou's drawings and models to give them to a nonprofit, to the University of Pennsylvania. That was the start of the archives. There were enough people coming to bat for him then as there were for saving the buildings in Ahmedabad recently.

Then there were dull times: a book here, my second book on Kahn, another book there. And then Dhaka was finished and more books came out. And then his son Nathaniel’s film [My Architect, 2003] made a big buzz and was nominated for an Academy Award. And then the Roosevelt Memorial came back, cemented by the film's success. And then a bunch of wonderful books on Lou came out. So, he’s been rising and will plateau, but he will plateau at a much higher place than he was before. He’s with Mies and with Wright, the Picasso of architecture. But the likes of you and the likes of me, we’ll be totally forgotten — well, I might be a footnote. Within my lifetime people have been held in such high esteem and then — poof! — they disappear… and sometimes they come back. Lou is back now, and that’s why I think my first book on him is returning at the right time.

The Notebooks and Drawings of Louis I. Kahn: A Facsimile

Edited by Richard Saul Wurman and Eugene Feldman

11.25 x 15 inches

96 Pages

76 Illustrations

Linen cover stamped in gold, plus paperback reader's guide

Falcon Press (1962), MIT Press (1973), Designers & Books (2021)

Purchase this book