I. M. Pei: Life Is Architecture, the highly anticipated exhibition on influential, world-famous architect Ieoh Ming Pei (1917–2019), opens at M+ in Hong Kong's West Kowloon Cultural District on June 29. Here we take a visual tour through a smattering of the drawings, photographs, and other artifacts that will be part of the full-scale retrospective.

Best known for the modernization of the Grand Louvre in Paris — aka the Louvre Pyramid — I. M. Pei's architecture blended tradition and modernity, historical forms and contemporary materials, east and west, and other seemingly irreconcilable opposites. Born in Guangzhou, China, in 1917, Pei moved the United States in the 1930s for architecture school, later working in New York City and eventually establishing his own eponymous practice there, the city he called home until his death in 2019 at the age of 102.

As can be seen from the images that follow, Pei's commissions spanned the globe, from the East Coast and other parts of the United States to China, the Middle East, and Europe. Rather than presenting his life's work in geographical or strictly chronological terms, the curators of I. M. Pei: Life Is Architecture (Shirley Surya from M+ and Aric Chen from the Niewe Institute) opted for a thematic presentation, using six areas of focus that define his singular body of work. This visual tour is structured accordingly.

Section 1 – Pei’s Cross-Cultural Foundations

This section shows how Pei’s upbringing in China and architectural education at MIT and Harvard University “formed the foundation of his ability to reconcile multiple sources of influence across cultures and between tradition and modernity,” per a statement from M+. Furthermore, “Pei adopted a transcultural approach that integrated the histories and conditions of a place with contemporary ideas and practices in architecture and society.”

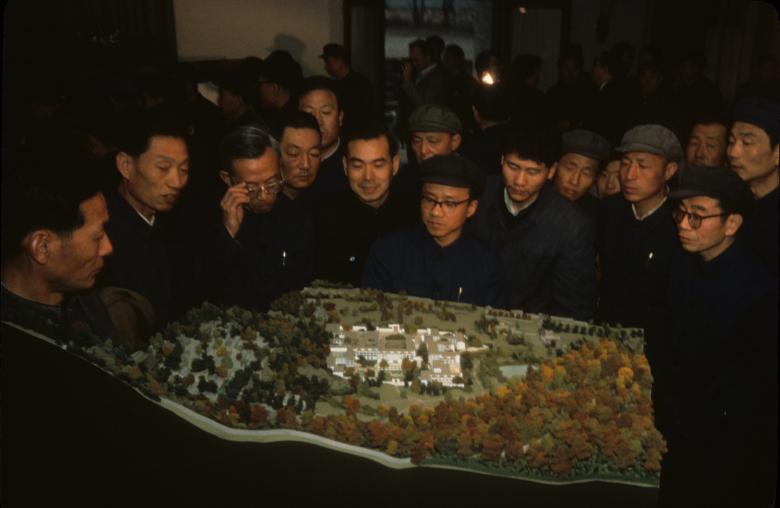

Section 2 – Real Estate and Urban Redevelopment

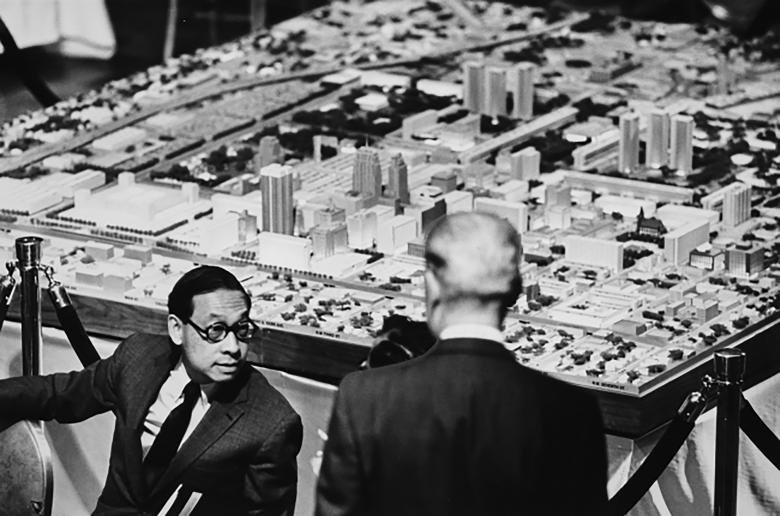

After graduating from Harvard Graduate School of Design but before establishing his own practice in 1955, Pei worked for New York City real estate developer Webb & Knapp, eventually becoming director. This section focuses on Pei's work at Webb & Knapp as well as his contributions to mixed-use planning, housing, and urban revitalization projects in the United States in his own practice in the 1960s.

Washington Urban Redevelopment (1953–1959), Washington, D.C., ca.1957. (Image © Pei Cobb Freed & Partners)

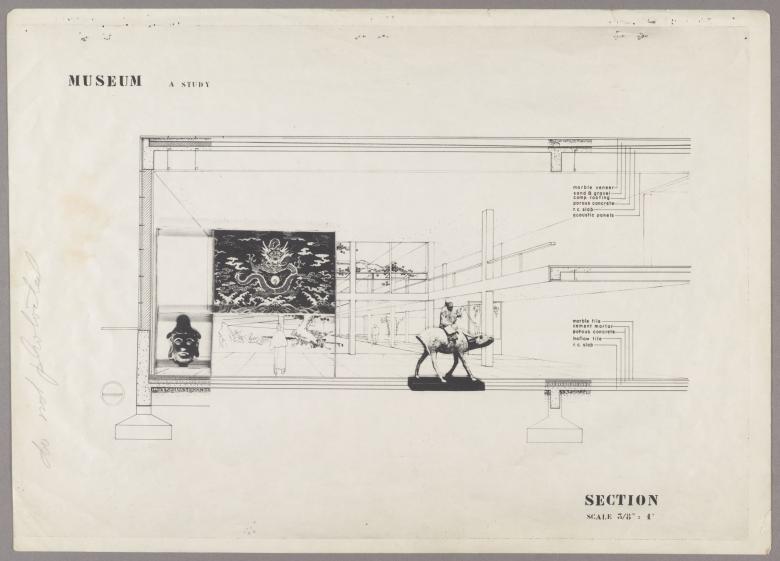

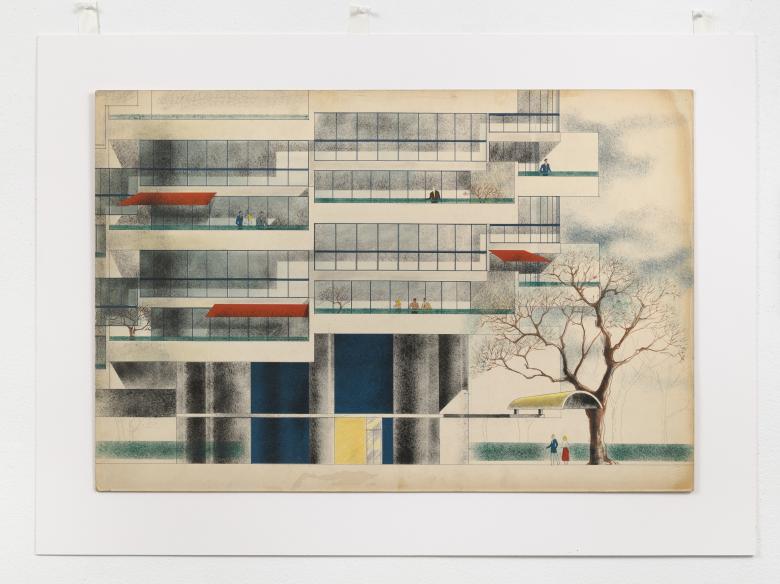

Section 3 – Art and Civic Form

Behind the Louvre Pyramid, Pei's most famous project is the East Building of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. These and other cultural projects are indicative of “his belief in museums as civic spaces, the importance of dialogue between art and architecture, and his deep affinity with the contemporary art of his time,” as explored in this section of the M+ exhibition.

Museum of Art (1961–1968), Syracuse, New York, ca.1961. Ink on paper. (Photo: M+, Hong Kong, photographed with permission © Pei Cobb Freed & Partners)

Section 4 – Power, Politics, and Patronage

The alliterative triumvirate of this section explores how Pei was able to engage with powerful clients, navigate the politics of major projects, and often convince his clients to pursue something more ambitious than what they had in mind. With his wide smile and impeccable manners, Pei managed to become a trusted collaborator in high-profile commissions that drew both immense support and public controversy.

Section 5 – Material and Structural Innovation

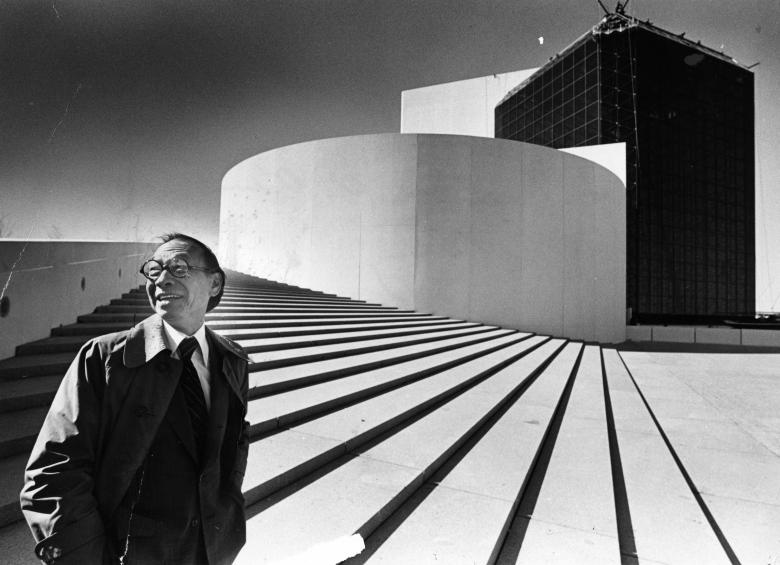

From Webb & Knapp and his own practice, and even to the projects he completed after retiring in 1990, Pei strove for inventiveness in materials and construction methods, particularly with concrete, stone, glass, and steel. The projects in this section “reveal Pei’s sensitivity toward building materials and their ability to animate the spaces we inhabit, as well as the great lengths Pei was willing to go to realize these solutions.”

Louvre pyramid, 1987. (Photo © Marc Riboud/Fonds Marc Riboud au MNAAG/Magnum Photos)

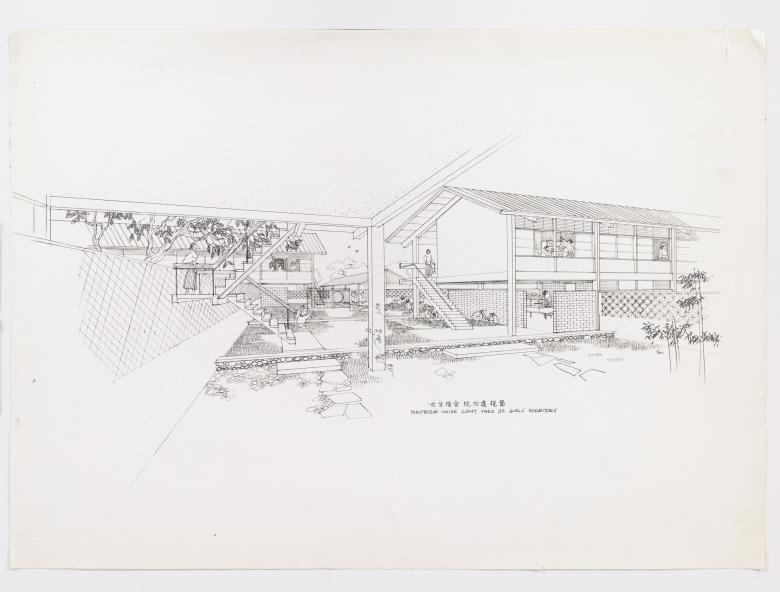

Section 6 – Reinterpreting History through Design

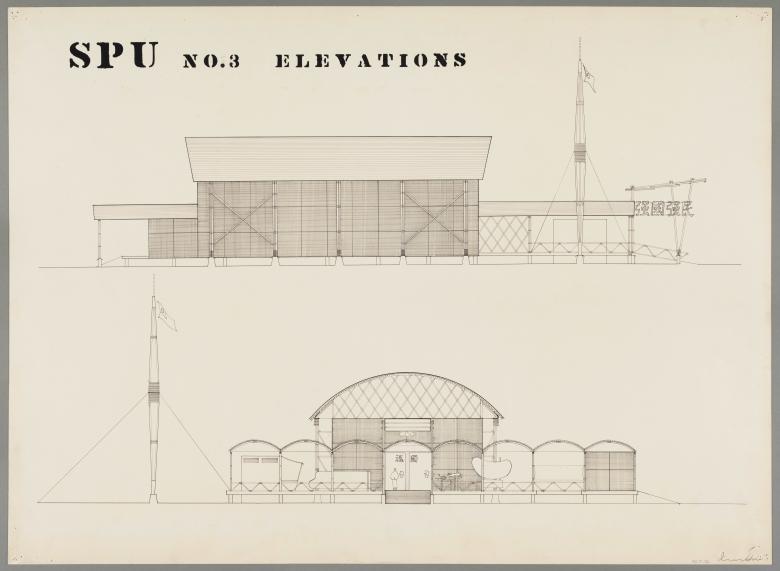

While Pei's projects this century, such as the Suzhou Museum in China and Miho Museum in Japan, seemed to signal a shift toward traditional forms, particularly from Asian architecture, he had long created buildings that tapped into the essence of cultural and historical archetypes. This section looks at how Pei “sought ways to make modern architecture’s technological advances and social ambitions engage with the diverse cultures and histories that informed his projects,” often at the risk of being denounced by critics and other architects.

Tunghai University (1954–1963), Taichung, ca.1955. Reprographic print. (Photo: M+, Hong Kong, digitized with permission © Pei Cobb Freed & Partners)

landscape, Suzhou Museum (2000–2006), Suzhou, 2021. (Photo © Tian Fangfang. Commissioned by M+, 2021)