A Labyrinth of Fairy Tales

The magic world of Hans Christian Andersen and his legendary fairy tales is on display in Odense, Denmark, in the House of Fairy Tales designed by Japanese architect Kengo Kuma. Ulf Meyer visited the H.C. Andersen House, sending us his impressions.

Creating a “world of dreams that is soft and immersive, with gentle curves and lots of vegetation” was at the core of Kengo Kuma’s design for the new museum in Denmark’s third largest city. After years of elegant coolness and paper-thin aesthetics, Kuma — a figurehead of contemporary Japanese architecture — has returned to warm, haptic and attractive surfaces made of wood with the “House of Fairy Tales” that is the H.C. Andersen House.

With the H.C. Andersen House, Kuma has proven that he can skillfully develop a promenade architecturale that takes children and adults alike into account — in this case leading them into realms of fantasy. Visitors meander down a narrow serpentine ramp into the large underground exhibition areas; it is an elegantly curving path reminiscent of Oscar Niemeyer's museum in Niterói. Once in the hall, visitors trace their own paths to their favorite fairy tales. The director of the new museum, Henrik Lübker, speaks of the “emancipation of the visitor” that the design allows.

H.C. Andersen, the most famous author of fairy tales in literary history, was born in Odense in 1805. Translating his unique literary world into the three — or is it four? — dimensions of architecture was a delicate task for Kuma. The temptation to be too graphic, too close to kitsch or too encroaching on the imagination of the visitor must have been great. But Kuma resisted. His museum, the new pride of Andersen’s birthplace, gracefully sidesteps a kitschy route. Along four general themed islands, the show, designed by Event, an “experience design agency” based in London, leads to twelve environments for the tales that made Andersen internationally famous.

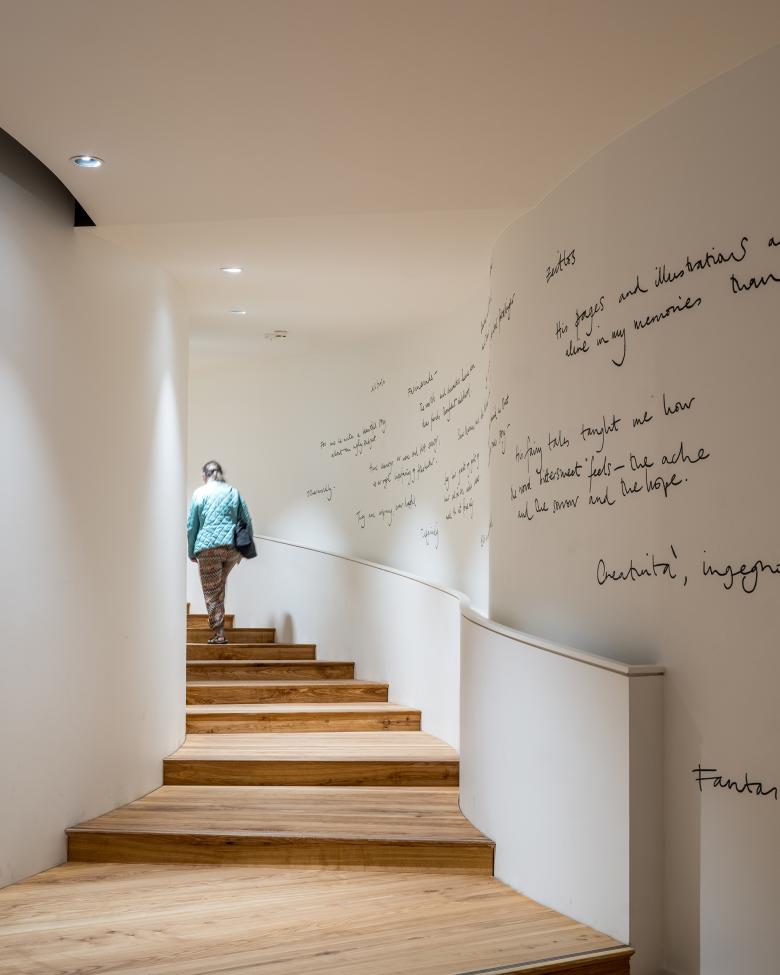

The use of modern media in the museum can be overwhelming, but thankfully the curators also incorporated 200 original artifacts from H.C. Andersen’s estate. Lübker, who exudes enthusiasm for Andersen, managed to pull off a few strokes of luck with his team for the scenography. Andersen's characteristic handwriting, for example, was used as signage in the form of black metal bands in front of the white plastered walls. Other tricks are of a spatial nature. In one of the fairy tale rooms you can look up into the daylight like the little mermaid through a glass floor of a water basin, while sinking sailors and amphibious mythical creatures appear from the darkness of the sea.

The urban pattern of Odense's eastern inner city is small in scale. Andersen's birthplace, which is right next to the new museum, has just one floor. For this reason, it was clever for Kuma to push the museum underground into a publicly accessible hill planted with hedge labyrinths. These hedges are not reminiscent of suburban homes; they are green walls that formulate interesting walk-in garden spaces and motivate movement. Such public green spaces could quickly become unsightly in other cities, but the high level of maintaining green spaces in Odense offers hope.

Only five wooden pavilions protrude above the green grade. The exhibition hall, with its elegant exposed concrete ceiling, is illuminated from an incised, sunken garden. Like an enchanted hortus conclusus, it offers a point de vue along the course, through which visitors can immerse themselves in Andersen's world. The boundaries between inside and outside, reality and fantasy and the everyday and its exaggeration become blurred. This ambiguity is the greatest strength of the museum’s biophilic design — it is a landscape instead of a landmark.

Kuma developed the sequence of circles and loops with his project manager Yuki Ikeguchi from Paris and the landscape architects Malin Blomqvist and Sune Oslev of Helsinki’s Masu Planning. “The source of inspiration for me is tradition," Kuma said, referring to the wooden framework of the small old town houses that you see all over Odense. Although he also stated that “wood is man's oldest friend," the bulk of the new building is a concrete structure. His design is restrained in terms of material and geometry, but as in a Japanese teahouse, the space is confronted with an almost infinitely large imaginary world.

The H.C. Andersen House succeeds in teasing out new aspects of famous fairy tales such as “Princess and the Pea” and “The Emperor's New Clothes,” but only a small part of this achievement is visible above ground in the round and oval pavilions in the museum garden. Built by an Austrian company, the mastery of timber construction is particularly evident in the pavilion called "Ville Vau," where children can let their imaginations run wild. The radially arranged spruce beams give the rooms in the pavilion atmosphere and grace.

Architecture, landscape design and exhibition design combine in Kuma’s “House of Fairy Tales” to create a magical world in which communication is not just about Andersen — it is also about how Andersen is communicated. An intense iterative process between client and architect, spanning across continents, led to this pleasing result. Fairy tales are neither linear nor transparent, and Kuma's fluid, non-perspective, decentralized architecture translates these phenomena without having to exhaust metaphors. His architecture invites visitors to rediscover the world and perceive stories from a different perspective.