A New Face for a Not-So-Old Icon?

The west facade of the former GSW Headquarters high-rise in Berlin, designed by Sauerbruch Hutton, is set to be renewed and redesigned. This is architecturally, ecologically, but also economically questionable and sends the wrong signal.

The former GSW headquarters is a piece of Berlin architectural history. When the complex, which consists of five independent structures, was built on Rudi-Dutschke-Straße in the 1990s, it was forward-looking — in more ways than one. The Sauerbruch Hutton team had succeeded in incorporating many historical points of reference from Berlin's turbulent (architectural) history: the baroque logic of the city's layout, the 19th-century densification, the bombings and reconstruction, the painful decades of division. In particular, the high-rise slice, with its main facade in shades of red, had an identity-forming effect — precisely because its colorfulness ran counter to the ideals of Senate Building Director Hans Stimmann, who otherwise characterized the city at the turn of the millennium, and thus provided refreshing architectural diversity. The design with which Sauerbruch Hutton won the competition in 1991 would probably have failed due to his strict specifications, which in the early 2000s led to the "petrification" of Berlin.

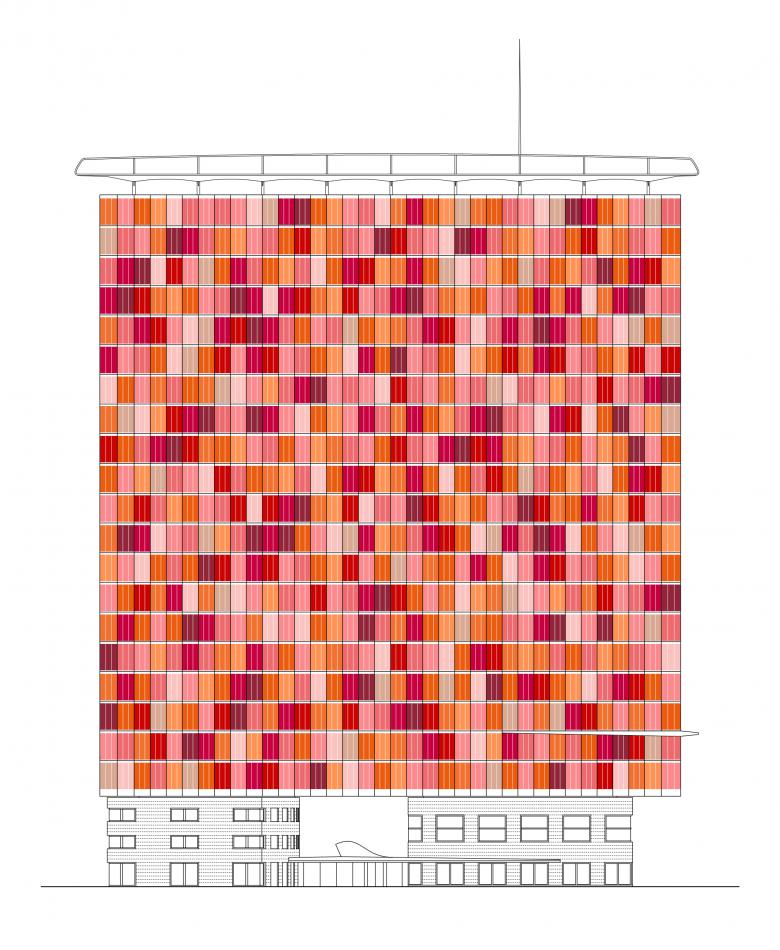

But the building ensemble was a milestone in ecological terms, not just in architectural and urban planning terms. Much of what is common sense today was innovative in the 1990s: the high-rise slice (today: "Rocket Tower") has a narrow floor plan to make the best possible use of daylight; its double facade allows for natural ventilation; and concrete was purposefully used as a thermal mass. The characteristic west facade consists of sunshades in nine special shades of red. These floor-to-ceiling perforated metal components can be both rotated and moved, so individual light and view control is possible. As such, the building constantly changes its appearance.

But now the former GSW headquarters has become the subject of a tangible dispute. What happened? Today, the complex belongs to Sienna Real Estate Property Management, who wants to give the high-rise a "new face." The aforementioned sun protection panels on the west side, which are now getting on in years, are to be replaced by fabric hangings that can only be rolled up and down vertically. The characteristic red tones, for many Kreuzberg residents part of the identity of their district, are also to disappear; the fabric hangings are to be designed in standard colors that deviate completely from the previous color scheme. Sienna GmbH, meanwhile, sees the new colors positively, as a statement quoted by the Tagesspiegel at the beginning of the month called it: "a makeover."

Sauerbruch Hutton responded at the end of May with an open letter to the owner. The architect's petition has since been signed thousands of times. Among the supporters are important personalities from the German architecture, art and culture scene, but there is also support from well outside of Germany: Barry Bergdoll, former MoMA curator and professor at Columbia University; critic and educator Aaron Betsky; Kees Christiaanse from ETH Zürich and KCAP Architects and Planners; historian Jean Louis Cohen; and artist Olafur Eliasson. Some people have taken to social media, notably S AM director Andreas Ruby. So far, Sauerbruch Hutton has received no response from the building's owner in regards to their appeal, but it is to be hoped that both parties will enter into a constructive exchange as soon as possible.

Meanwhile, it is uncertain whether the Sauerbruch Hutton team can benefit from the fact that architectural works are protected by copyright in Germany. The interests of the author would have to be weighed against those of the owner, so the outcome is open. The quarrels surrounding the renovation of the Gasteig cultural center in Munich, for example, show how complicated, protracted and also unattractive such a dispute could become.

Berlin is currently one of the most architecturally and politically interesting cities in Europe. The challenges for architects, politicians and developers are enormous. There is a lack of living space and the question arises as to whether the mass construction of new residential buildings alone is the solution, or whether intelligent use of the existing stock, measures against speculation, and a reduction in the amount of space required per capita are needed more. Future urban development must also be compatible with the goals of climate protection and, in any case, be of high architectural quality. And all this in a time of pandemic and war, when investments are more difficult than ever. Especially against this background, the decision of Sienna Real Estate Property Management is all the more unfortunate. A key building block in Berlin's recent architectural history would be significantly impaired — and a pioneer of climate-conscious construction at that. In addition, much avoidable waste would be created and a considerable amount of CO2 would be emitted.

A better solution would be to repair the striking facade of the multiple-award-winning structure. In this way, the owner could send a contemporary signal. It would promote climate protection and appreciation of what already exists, and it would further strengthen the identity of the district. This would make ecological, economic and social sense. It is time to act responsibly and farsightedly — for everyone.