Last month David Chipperfield Architects won the competition to expand the National Archaeological Museum in Athens. Ulf Meyer spoke with David Chipperfield and Alexander Schwarz, partner in Chipperfield’s Berlin office, about the project and their approach to designing museums.

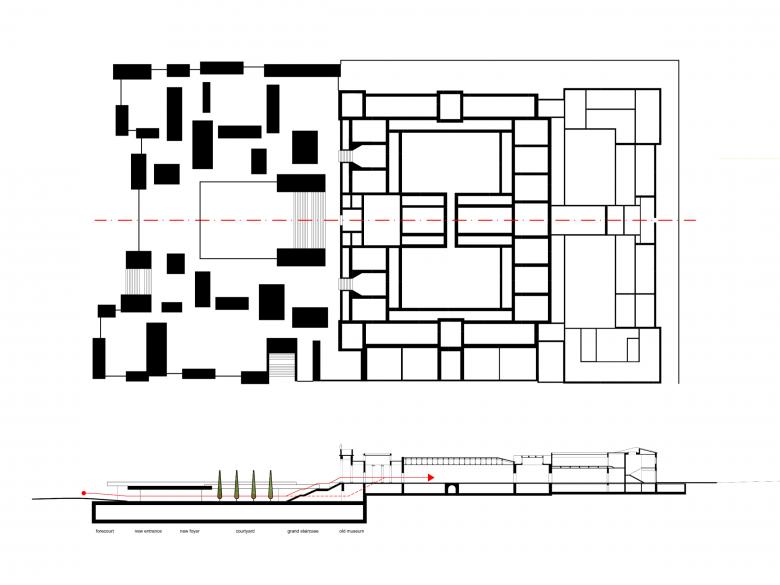

World-Architects (W-A): You have just won the competition for Greece’s biggest museum, the National Archeological Museum in Athens, with a scheme that is buried underground.David Chipperfield (DC): It is a socle project. We are making a socle into a building. We have a similar set of challenges that Mies van der Rohe had with the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin in the 1960s. Mies gave orientation to the rooms in the socle through a garden courtyard; we are doing the same here: the central courtyard gives identity and character to spaces within a socle.

We've extended the architectural opportunities by bringing light down within the structure of the socle. The courtyard is a critical element, not only to give orientation and quality to the galleries, but to connect the socle with the temple. The courtyard is the link between the two things: the staircase and the temple facade, a central space of the socle.

DC: Plinth suggests that something stands on top. If we said the building has a plinth, we would think it's the thing which something stands on. I've inherited the notion that a socle is something which can be occupied. It has a space inside, but a plinth tends not to. But this is not very precise.

Alexander Schwarz (AS): This ambiguity of structure, which is quite solid, buries space. That's a fundamental idea to this architecture. It hovers between being built and being excavated. A socle is something in between nature, in between typography and architecture.

DC: It's a theme, the Acropolis is a socle.

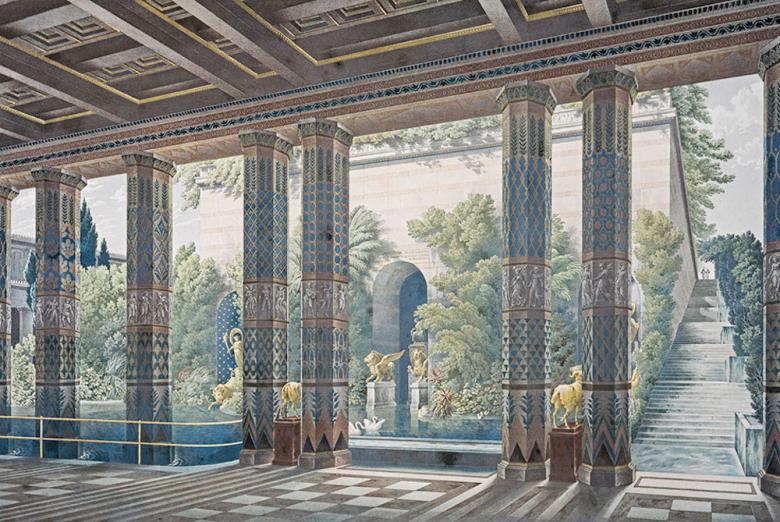

AS: Schinkel used it for Schloss Orianda. It is this idea that the built topography is the museum. It's also climatically good because if you put things into caves, they don't deteriorate. It's a sustainable place for museum to keep things. The problem is how do you make them accessible and how do you bring in light?

DC: The task of the competition anticipated that we would bury our proposal in the garden. You're going to end up with a roof, so we embraced the idea that this roof shouldn't just be a roof but a public space. We see the project in two different ways: The museological and the urban task, and they feed each other. The 19th century museum as represented by the existing building carries with it a certain idea of detachment. We know the story, the problem of the 19th-century museum well: something up a staircase, in this case across a slightly deserted urban space, that encloses its treasures. Recently, the museum has changed its priorities to being not just a place for dedicated visitors, but a touristic destination and attraction. But in a positive way. The museum's concern is not to bring people in who are familiar with museums, but people who are less familiar.

DC: Absolutely. One of the problems a lot of museums have is that their visitor numbers are asymmetric in terms of tourists versus non-tourists. That's a particular problem with big national museums. On Museum Island in Berlin, at the James-Simon-Galerie, it's a double-edged sword: it is about accommodating more tourists — processing them and providing orientation — but it's also providing facilities used by residents. The lecture hall, the shop and cafe, the changing exhibition hall have appeal to people who live in the city. When I go to the British Museum, I go to see the changing exhibitions, not the Elgin Marbles or Nefertiti each time. In Athens, the garden, the courtyard, and the new galleries can have a compensatory appeal in this idea that it's a place to go.

DC: There are two issues. If we were doing a painting museum, the design would be neutral, white, made of gypsum. In an archaeological museum, there's an opportunity to think that the walls have a material; in this case, we use a mixture of compressed earth and concrete to create a passive background that still has material presence. That is quite difficult in most museums; there would be resistance to that. For marble and bronze objects, we were interested in making rooms with an architectural materiality from the beginning.

Second, materiality is not just a decorative surface, but also the substance of the building. If that substance also could appeal to contemporary concerns about where materials come from — not putting them on a boat from India or China or somewhere, but digging them out of the ground 100 kilometers away — then all of a sudden you're starting to bring together a series of coincident ideas: sustainability in terms of material and aesthetic; in terms of construction and scenographic presentation of objects; in terms of substance and stability, both structurally and thermally; in terms of climate …

AS: The floor plates have a wide span up to 20 meters. We have a flat ceiling and upturned beams. Within the depth of the beams there is a meter of soil for plants. Some of those volumes that organize the space are just massive planters where monumental trees can grow. These solid blocks on the plan, some of them bury rooms, some have minor things inside, and some of them are just solid blocks of earth that enable the scale of trees on the roof.

DC: It’s not only soil, it's water retention. One of the things we have to do in cities is stop water just going down the drain. Water should be spending more time in soil.

We took the idea of the socle as a clue about it being something heavy, not light. That heaviness, we believe, is sympathetic to an idea of the presentation of the collection. Rooms are formed by the structure: the material surfaces are not just decorative; they are actually what the building is made of. They confirm the idea that the garden is sitting on a ground, like solid ground with holes in it more than a building with a heavy roof.

AS: The building is without a facade. It's porous structure, and due to the topography of the city it becomes accessible. The facade is for the building on top; we don't want to compete. Starting with the neoclassical central axis, the courtyard mitigates between the two orders, but then becomes a center of a free composition of walls. The neoclassical gets dissolved into something archaic or modern.

DC: It’s more porous because this new field of galleries is something you must go through in order to arrive at the existing museum. We created a spatial sequence that is not a series of enfilade rooms like in the classical building. Instead, you have a landscape of spaces with diagonal views that create a sense of enclosure and orientation. One of the weaknesses of a 19th-century museum is the repetitiousness; we didn't want to create that type of spatial structure in this building. On the contrary, we felt that this could be much more scenographic and a much more dramatic way of presenting objects.

DC: We were very keen to make sure that the new building is an extension to the existing and that what we were trying to do is to strengthen the institution as a singular thing. Not to create the old and the new. That's why it's important for us to set the building slightly higher than the brief suggested, so the continuity between the new galleries and the existing building is much more comfortable. The brief implied that we set the building lower, but we felt that would have a problem because the transfer from the new galleries to the old ones would be much more uncomfortable — or at least more explicit.

DC: Every project comes with problems. I don't think taking longer makes things necessarily better. You have three exercises: one is planning, one is permits, the third is construction. When projects take more time, it's not like they’re built more carefully. Time is lost in the permits, or in in a bad planning process, not because the craftsmen say, “let's make the building the high quality.” I don't think there's any great initiative to going longer, but at the same time, it's part of any architectural realization. You wouldn't be an architect if you got frustrated.

AS: Good momentum for a project can be often too fast, but that will not be the case here. Of course, it is dangerous if it takes too long. I think, especially with complicated or historic situations, it's good to learn about the building during the process. It’s good to feed things you’ve learned about what’s there back into the design. It's a bit different if you start with a new structure, then your strongest idea would be in the beginning and you don't need this learning process.

DC: This is not a restoration project, it's a project which grows out of an existing building, but our experience working with restorations is that if you start with something people already have an affection towards or can identify with, you can draw uncommon sympathies. If you're building a new building, you have to persuade everybody to like something that they don't know anything about. If you're persuading them to restore Mies van der Rohe’s Neue Nationalgalerie, they already have an affection for it; the common object is useful. There's an advantage here, in Athens, in that there is a common object: not necessarily the extension, but the existing.

To what degree can the architect help the process? Do we have any value in the realization process? One of the things we've grown up with is the notion that projects like this, you don't have an entitlement to do it; it's not naturally going to happen. To some degree, you are pushing it up the hill. When projects have a strong public importance, architects have to accept that, you have to participate in that. For the Neues Museum, we had to communicate a lot: internally, with the client, and externally in terms of public opinion and concerns that the city and the country had. Public projects of this importance come with communication requirements.

It's also important that projects have transparency. We have done a lot of work in small American cities, like St. Louis, Anchorage, and Des Moines. You may think that America is undemocratic and not community-based, but in St. Louis we presented the project every six months to the city, so by the time the building was finished, everybody in St. Louis knew about the project. It required donations, the donors were part of the community, and they wouldn't give money if they thought the project wasn't going to be good. I always thought it would be the opposite. When we did the Museum of Modern Literature in Marbach, I don't think anybody in Germany knew it was happening. Then one day we opened the door. Architects have to be able to explain their projects from the perspective of common sense, not their architectural genius. The grounded-ness of our projects help. Politicians are always nervous and don’t want things to go wrong.

DC: Berlin is known as the Athens of the North, so this must be the Berlin of the South. It is a building by a German architect [Ernst Ziller] who was influenced by classic German architecture from the North, which in turn was inspired by Greek architecture. It’s a ping-pong game we joined in round four. There is a strange resonance and that is something that we are sensitive to.

I have the privilege of benefiting from the creative impulse of others. We are in a postmodern period. Our work is a responsive approach. Our work deals with transient times. We enjoy working closely with history because it becomes a rich place to dig. The Neues Museum was potentially a nightmare project; our approach — digging and finding — turned it into a positive thing. It is a strange approach because you expect artists to be original and creative, wanting to impose their view. We always look for making sense of things. It is an appropriate position for contemporary architecture: engagement and collaboration and excavation. We are protected by the creativity of those who came before us. Uniqueness comes with the place.

W-A: That is an antithesis to the Bilbao Effect. Thank you very much for the interview.

Related articles

-

-

-

-

Isabel Zumtobel: 'We Believe in the Power of Design to Change the Future for the Better'

World-Architects Editors | 18.11.2025