'Mies van der Rohe: The Collective Housing Collection' by Fernando Casqueiro

Black and White and Mies All Over

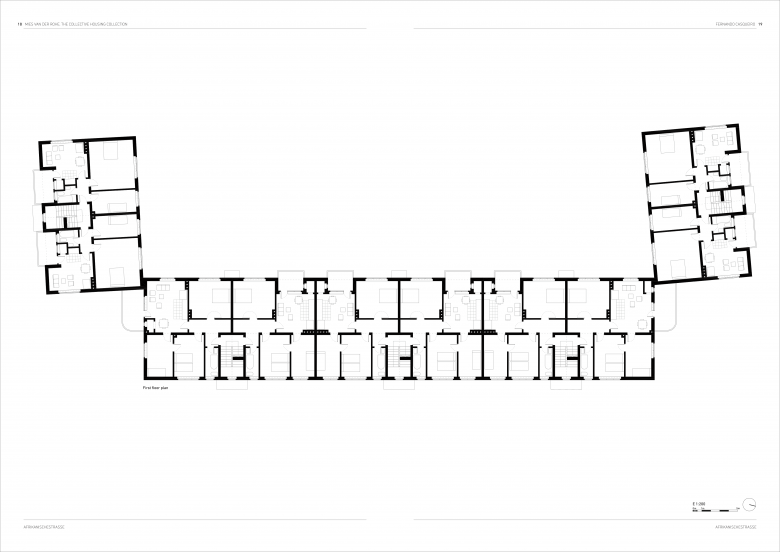

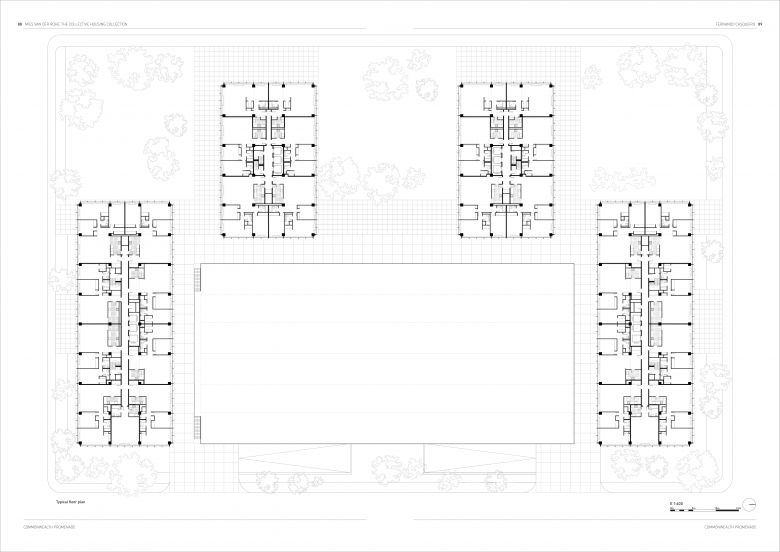

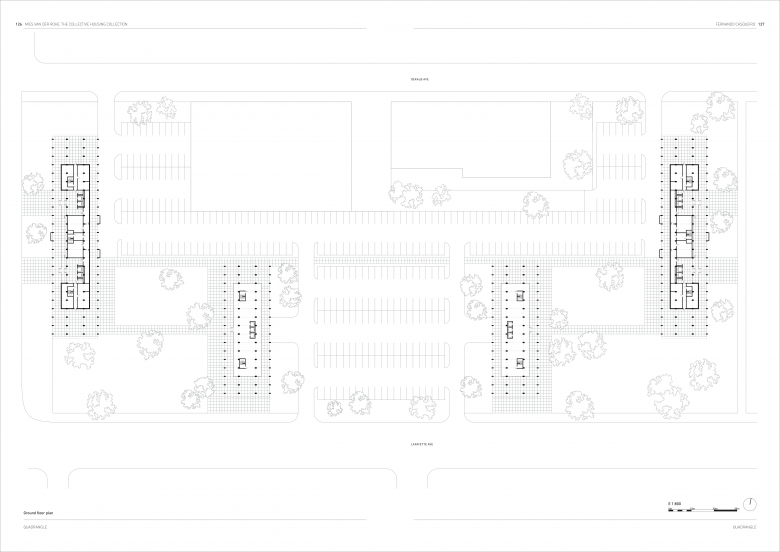

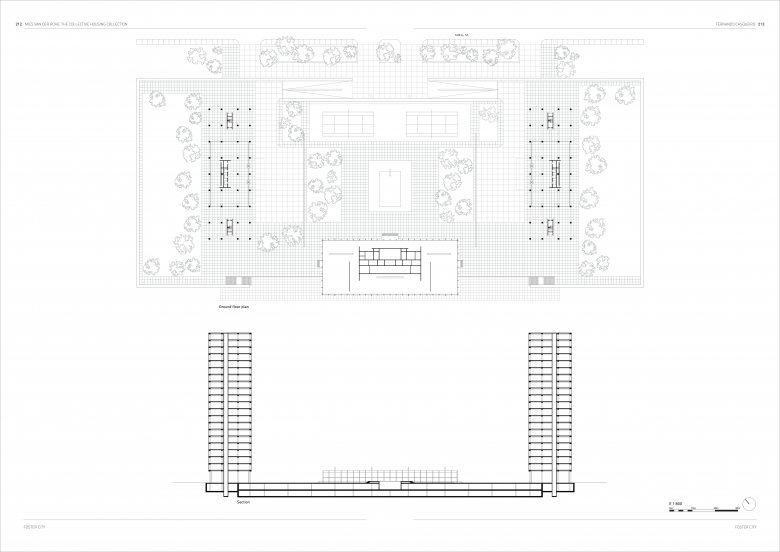

Mies fans rejoice: A new book documents 36 built and unbuilt collective housing projects designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe over a 40-year period — from low-rise ensembles built in Germany in the mid-1920s to a pair of mid-rise slabs completed in Montreal two years before his death in 1969 — in redrawn floor plans, elevations, and sections.

At first glance a book devoted to the collective housing projects designed by Mies van der Rohe— apartment buildings in the United States in the 1950s and 60s, mainly — seems an odd choice. Mies is more celebrated for single-family houses (Farnsworth, Tugendhat), cultural buildings (Barcelona Pavilion, Neue Nationalgalerie), and educational buildings (Crown Hall and the rest of IIT); and his influence was most pronounced in the office buildings he designed for Chicago (Federal Center), New York (Seagram Building), and other cities. Mies designed dozens of apartment buildings but the ones of note can be counted on one hand, with 860/880 Lake Shore Drive in Chicago topping the short list. Therein lies the value in Mies van der Rohe: The Collective Housing Collection by Fernando Casqueiro, associate professor at ETSAMadrid: The book collects all of the collective housing projects designed by Mies, bringing to light overlooked projects and presenting them alongside his more famous works so comparisons can be made and a comprehensive view of his office's residential designs can be appreciated.

Systematic and scientific are two good terms for describing the presentation of apartment buildings assembled by Casqueiro in collaboration with architects Carlos Revilla Madrigal, Luis Miguel Sanz Rodríguez, and Nikolay Ilkov. Immediately, in the author's introduction, a chart of the 36 housing projects illustrates if they were featured in any of 21 Mies monographs published between Werner Blaser's Mies van der Rohe: The Art of Structure in 1965 and Detlef Mertins' Mies in 2014. Only four projects appear in ten or more of the monographs (Weissenhofsiedlung, 860/880 Lake Shore Drive, Commonwealth Promenade, Lafayette Towers) and only one publication features most of the buildings: the 19-volume The Mies van der Rohe Archive edited by Franz Schulze and George Danforth, published in 1992/93. But how many people have any or all of those Archive volumes? Outside of libraries, I'd wager very few. The chart, which also indicates what types of documentation are provided for each project in each monograph (site plan, section/elevation, floor plans, photos), reveals the paucity of readily available visual information on Mies's apartment buildings. This book, in turn, fills a sizable hole.

Two pages after the helpful publications chart is a numbered list of the 36 projects, starting with Afrikanischestrasse and Weissenhofsiedlung, built in Berlin and Stuttgart, respectively, in 1927, and ending with Nun's Island I and II, both completed in Montreal exactly 40 years later. One could surmise that Mies devoted the same number of years to exploring the problem of collective housing, but a full 20-year gap is visible between the two German projects and the first apartment building he realized in the United States: Promontory, built in Chicago in 1949. As such, 34 of the 36 projects were designed in a fruitful two-decade period following the end of World War II. The list indicates that exactly half of the 36 projects were built (15 were unbuilt, three were sketches), but the most revealing designation is that 21 of the projects were designed by Mies's office for developer Herbert Greenwald or for Metropolitan Structures, the successor company established following Greenwald's tragic death in 1959. Starting with Promontory, Greenwald was a repeat client par excellence for Mies; they worked together on 860/880 Lake Shore Drive, Lafayette Towers, Nun's Island, and numerous other projects in Chicago, New York, Detroit, Baltimore, New Jersey, and California. Greenwald died in an airplane crash on February 3, 1959 (the same day Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and "The Big Bopper" died in another plane crash), when he was just 43 years old; we can only imagine where he and Mies might have pushed collective housing in the last decade of the architect's life if he didn't die so young.

Following the succint but valuable introduction is the presentation of the 36 collective housing projects that comprise “The Collection.” Presented in chronological order, the projects are given a consistent format that starts with a box with project data (stories, height, structural bays, no. dwellings, site area, density, etc.) and includes descriptive and critical text by the author, at least one b/w photograph, and pages of drawings that move from 1:5000 site plans to 1:150 unit plans, with floor plans, elevations, and sections in between. The line drawings are clean, free of any text outside of a title and a scale; furniture and fixtures in the floor and unit plans allow the layouts to be understood without text. “The intention is only to describe and analyze the set of projects and buildings carried out by Mies in this architectural genre,” Casqueiro explains in the introduction, continuing: “The application of this work is up to its readers and user.” For this reader, at least initially, the book provided a trip down memory lane, sparking some Mies-related memories from my years living in Chicago: dinner and drinks at an architect's apartment in 860/880 Lake Shore Drive; an Oscar watch party in a 2400 Lakeview apartment; and numerous evenings spent on a friend's terrace overlooking Commonwealth Promenade, where I could peer at residents living their lives on full display behind the aluminum-and-glass curtain wall.

Most rewarding to this reader was discovering the lesser-known projects and poring over their plans with the same intensity as the apartment buildings I was already familiar with. One standout was the Sheridan–Oakdale Apartments, a 14-story L-shaped building with 213 units in Chicago's Lakeview neighborhood, less than two blocks from Commonwealth Promenade. Even though I lived in neighboring Lincoln Park for a few years, I drew a blank on this building. Looking at a photo, one would be excused for not realizing it was designed by Mies. It was completed in 1951, the same year as 860/880 Lake Shore Drive, but instead of an expressive steel facade akin to that pair of buildings, the building at Sheridan and Oakdale echoes Promontory, with exposed concrete beams and columns, the latter stepping as they ascend the building. Now punctuated by a grid of window air conditioners, the sales literature from 1951 that Casqueiro and his collaborators based their drawings on shows a taut, glassier exterior with interiors considerably more modern than their contemporary reality. The drawings in the book reveal, among other things, how Mies dealt with the awkward inside corner of the L-shaped plan, creating a sizable double-exposure two-bedroom unit that retains privacy. Casqueiro is not impressed though. He calls attention to “the crudeness, the ineptitude, the routine, the lack of talent” on display in this “anomalous building.” Perhaps the disappointment arises from the fact Mies designed the building for another client, not Herbert Greenwald.

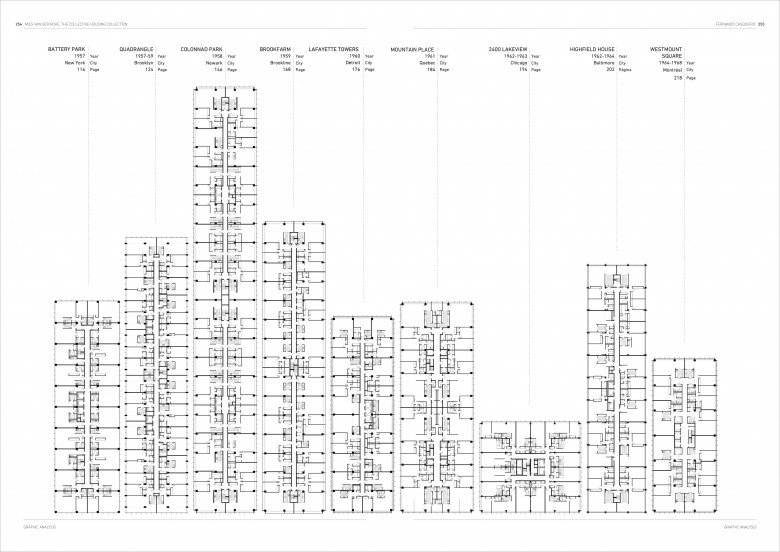

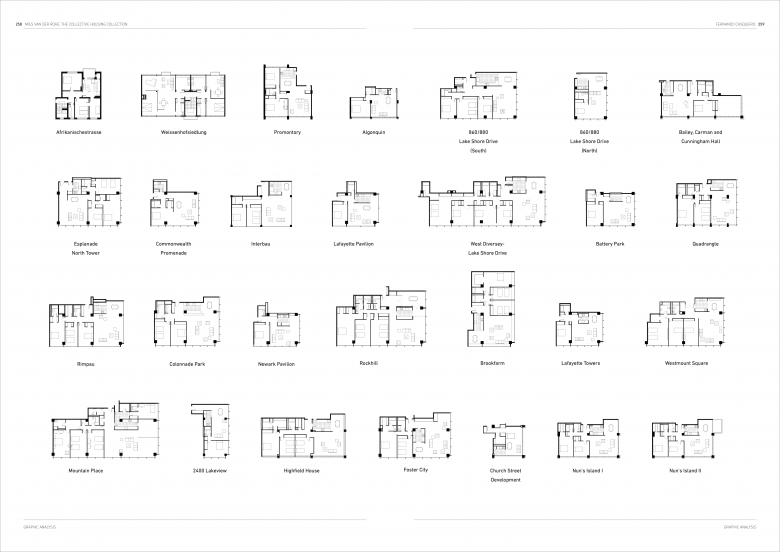

Following “The Collection” is another 50 pages of material. A three-part “Graphic Analysis” starts with the site plans, showing site extents, site coverage, and building footprints for 30 of the 36 projects. Floor plans follow, revealing the prevalence of the 860/880 Lake Shore Drive “type” (a rectangular prism three bays wide by X bays long). Last are the unit plans, which focus predominantly on the corner plans that are more sizable than the studio apartments in many of Mies's apartment buildings. A “Statistical Study” follows, presenting text and charts on density, FAR, net/gross areas, and other quantifiable information. Casqueiro's “Conclusions” come next, attempting to justify the effort that yielded the book's documentation, but even that is followed by more material: two “Annexes,” one looking at the structure of Mies's offices and some notable collaborators; and one tracing some of the technological advances that transpired over the architect's long career, advances that impacted the apartment buildings he designed.

Mies van der Rohe: The Collective Housing Collection offers more than just drawings. It is comprehensive, both with its architectural drawings and in addressing the issues around Mies's collective housing projects in the middle of last century. It is a rewarding book, but it is not one without its flaws. The text for the English version is awkward, in need of a good copy editor who could make it more readable and less frustrating. The drawings are exemplary, but some of the linework (furniture, door swings, paving, structural grids, etc.) is too fine, hard to see in less-than-ideal light conditions. And one anomaly in the nearly faultless floor plans bugged me: The conventional diagonal break indicating one stair going up and one going down is missing; in its place is a poché section the width of a tread, which reads like a wall is in the middle of the stairwell, an unfeasible proposition. A CAD error? Perhaps. Whatever the case, this graphic oddity fortunately does not detract from appreciating and understanding the floor plans and other drawings in this valuable collection.

Mies van der Rohe: The Collective Housing Collection

Fernando Casqueiro

23 x 30 cm

306 Pages

Paperback

ISBN 9788409456635

a+t architecture publishers

Purchase this book